Flintlock Gun Part

August 2010

By Annette Cook, MAC Lab Public Archaeology Asst.

In June, 2010, a summer intern working with Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum staff was digging a unit in the kitchen area of the Smith's St. Leonard site (18CV91). Upon unearthing a small, oddly-shaped metal artifact in the plowzone layer, he held it up and announced "I think I found a goose!" The object was approximately 7 cm long and did, in fact, curve in a manner reminiscent of a bird's neck. It even had a large head and pronounced "beak." What on earth could this object be?

In June, 2010, a summer intern working with Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum staff was digging a unit in the kitchen area of the Smith's St. Leonard site (18CV91). Upon unearthing a small, oddly-shaped metal artifact in the plowzone layer, he held it up and announced "I think I found a goose!" The object was approximately 7 cm long and did, in fact, curve in a manner reminiscent of a bird's neck. It even had a large head and pronounced "beak." What on earth could this object be?

Closer inspection and cleaning revealed that the object was the hammer, also referred to as the cock, from a flintlock gun. Furthermore, the gunflint was still firmly locked in place between the gun cock's jaws. The piece seemed to be in near perfect condition, with only a small chip missing at the base of the artifact (Figure 1). Appropriately enough, this type of gun hammer or cock is often referred to as a goose-neck cock (Brown 1980: 182). The flatness of the body, as well as the slotted jaw screw, match descriptions of both British and French gun cocks (Peterson 2000: 167, 173).

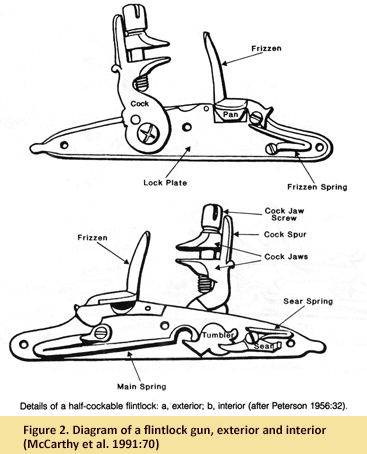

Flintlock weapons were so named because the hammer/cock part of the firing mechanism held a piece of flint. The gun cock was moveable and would be pulled back into the half-cocked position for loading, or to the fully cocked position in preparation for firing. Ignition was provided by the pull of a trigger, which caused the cock to spring forward, striking the flint against a steel plate, called a frizzen, yielding sparks (Figure 2). The sparks fell into a shallow pan containing a small amount of gunpowder igniting it. This fire traveled through a tiny hole leading into the barrel of the gun, which would be loaded with gunpowder and ammunition, causing the gun to discharge (Moore 1967: 4-5). The term "flintlock" may refer to any weapon using that particular firing mechanism, or to the mechanism itself. Flintlock guns could be long barreled firearms, such as muskets and rifles, or short barreled pistols, blunderbusses, and carbines.

Flintlock weapons were so named because the hammer/cock part of the firing mechanism held a piece of flint. The gun cock was moveable and would be pulled back into the half-cocked position for loading, or to the fully cocked position in preparation for firing. Ignition was provided by the pull of a trigger, which caused the cock to spring forward, striking the flint against a steel plate, called a frizzen, yielding sparks (Figure 2). The sparks fell into a shallow pan containing a small amount of gunpowder igniting it. This fire traveled through a tiny hole leading into the barrel of the gun, which would be loaded with gunpowder and ammunition, causing the gun to discharge (Moore 1967: 4-5). The term "flintlock" may refer to any weapon using that particular firing mechanism, or to the mechanism itself. Flintlock guns could be long barreled firearms, such as muskets and rifles, or short barreled pistols, blunderbusses, and carbines.

Earlier versions, including wheel-lock and snaphaunce guns, date from the 16th century and were considered a vast improvement over prior "hand gonnes" requiring the use of wicks or slow burning matches to fire the weapons (Hogg 1980: 14-23 and Peterson 2000: 159). True flintlock guns were probably developed in France and came into use in the early 17th century (Hogg 1980: 24). The flintlock gun was lighter, more balanced, and more dependable in inclement weather conditions (Hogg 1980: 14 and Peterson 2000: 159). Flintlock weapon technology was the standard for approximately 200 years, with little variation, until being replaced by percussion cap weapons in the early 19th century (Brown, 1980: 75).

Earlier versions, including wheel-lock and snaphaunce guns, date from the 16th century and were considered a vast improvement over prior "hand gonnes" requiring the use of wicks or slow burning matches to fire the weapons (Hogg 1980: 14-23 and Peterson 2000: 159). True flintlock guns were probably developed in France and came into use in the early 17th century (Hogg 1980: 24). The flintlock gun was lighter, more balanced, and more dependable in inclement weather conditions (Hogg 1980: 14 and Peterson 2000: 159). Flintlock weapon technology was the standard for approximately 200 years, with little variation, until being replaced by percussion cap weapons in the early 19th century (Brown, 1980: 75).

An expert shooter could load and fire his weapon every 15 seconds. In regimental warfare, which involved several lines of soldiers lined up shoulder to shoulder, and firing all at once, this meant that in an average attack, multiple volleys could be fired at a charging regiment. Although flintlock muskets were not very accurate beyond 80-100 yards, speed and the sheer number of ammunition fired was more important in regimental battle (Peterson 2000: 160).

It is not known how or why the gun cock ended up in the Smith's St. Leonard kitchen, nor have any other known gun parts been found on the site to date. Gunflints, musket balls and smaller lead shot have been recovered. So why wasn't the rest of the gun found in close proximity? Perhaps it is because the flintlock mechanism was the most fragile and often broken component of a flintlock weapon. These parts were also easily replaceable, thus allowing the repair and continued use of a gun (McCarthy et al. 1991: 72). It is possible that, with its chipped bottom, the gun cock had been removed and discarded during repairs to a weapon. Or, possibly, the damage occurred later, and the piece was being kept as a possible replacement part for a broken gun. At the Addison Plantation site in Prince Georges County, Maryland, numerous individual gun parts were found, but no complete weapons. As commander of the county's militia, Thomas Addison maintained an armory, and useable gun components were undoubtedly kept for future use (McCarthy et al. 1991: 74).

Although Smith's St. Leonard was not a military post, weapons would have certainly been available for protection, as well as for the procurement of food. Only time and further excavation will reveal whether more gun parts are to be found.

| References |

|

| Brown, M.L. |

| 1980 |

Firearms in Colonial America. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington City. |

|

| Hogg, Ian V. |

| 1980 |

An Illustrated History of Firearms. Quarto Publishing, Ltd, London. |

|

| McCarthy, John P., Jeffrey B. Snyder and Billy R. Roulette, Jr. |

| 1991 |

Arms from Addison Plantation and the Maryland Militia on the Potomac Frontier. Historical Archaeology, Journal for the Society for Historical Archaeology, Volume 25, Number 1: 66-79. |

|

| Moore, Warren |

| 1967 |

Weapons of the American Revolution. Funk and Wagnalls, New York. |

|

| Peterson, Harold L. |

| 2000 |

Arms and Armor in Colonial America 1526-1783. Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, New York. |

|