Signed, "Sealed", Delivered!

October 2011

By Nichole Doub, MAC Lab Head Conservator

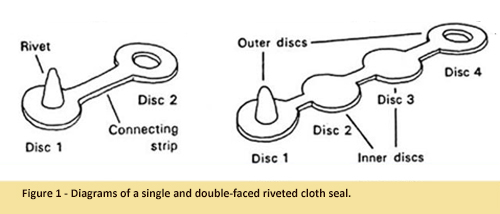

All consumers want assurances as to the quality of products and may prefer one manufacturer over another. This is as true historically as it is today. Cloth seals or bale seals are one method of assurance. These lead seals were attached to the outside corner on a bolt of cloth and were often impressed with a variety of marks including dates, symbols and hand scratchings. Historically, these seals indicated that the product being traded had undergone some form of inspection both for quality control and taxation purposes (Egan; 1994, 1-3). Cloth seals came into use in the early 1300s in England after King Edward I ordered the official supervision of manufactured woolen cloth (Endrei and Egan 1982,64). This practice, called alnage, was abandoned by the British government in 1724 (Luckenbach and Cox; 2003, 17). Knowing this, cloth seals can be useful to archaeologists both as a dating tool and for identifying trade sources.

All consumers want assurances as to the quality of products and may prefer one manufacturer over another. This is as true historically as it is today. Cloth seals or bale seals are one method of assurance. These lead seals were attached to the outside corner on a bolt of cloth and were often impressed with a variety of marks including dates, symbols and hand scratchings. Historically, these seals indicated that the product being traded had undergone some form of inspection both for quality control and taxation purposes (Egan; 1994, 1-3). Cloth seals came into use in the early 1300s in England after King Edward I ordered the official supervision of manufactured woolen cloth (Endrei and Egan 1982,64). This practice, called alnage, was abandoned by the British government in 1724 (Luckenbach and Cox; 2003, 17). Knowing this, cloth seals can be useful to archaeologists both as a dating tool and for identifying trade sources.

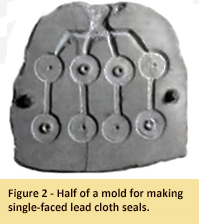

The most common type of commercial cloth seal is the riveted form, whereby the seal was attached by folding two lead disks, connected by a thin strip, around either side of a corner of cloth so that the rivet could be pushed through  the cloth and the corresponding hole in the other disk (Figure 1). The seal was then hammered with one die, or between two dies, to close it in place and to register the necessary information on its surface (Egan; 1994, 4). The symbols on the seals can include information about the date and region of production/inspection as well as a wide range of makers’ marks, personal initials and notes for length, width and weight. Symbols indicating alnage include the crown, coats of arms, griffins or lions rampart, heads of royalty, etc. (Luckenbach and Cox; 2003, 18).

the cloth and the corresponding hole in the other disk (Figure 1). The seal was then hammered with one die, or between two dies, to close it in place and to register the necessary information on its surface (Egan; 1994, 4). The symbols on the seals can include information about the date and region of production/inspection as well as a wide range of makers’ marks, personal initials and notes for length, width and weight. Symbols indicating alnage include the crown, coats of arms, griffins or lions rampart, heads of royalty, etc. (Luckenbach and Cox; 2003, 18).

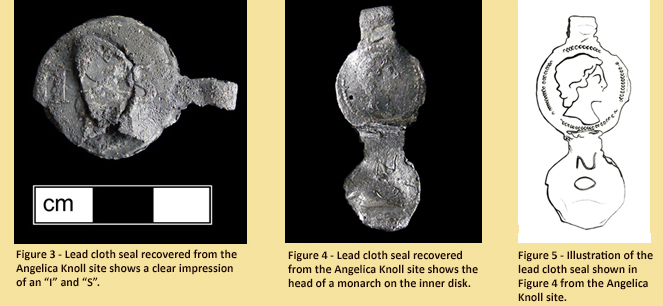

A number of lead cloth seals were recovered from the Angelica Knoll site (c. 1677-1735) excavation in Calvert County, MD. Of the Angelica Knoll cloth seals, two show clear striking/impression marks. The seal in Figure 3 has a clear impression of an “I” and “S”. It is unusual that the impression has been made on the second disk rather than the blank first disk. The alnage seal in Figure 4 shows the head of a monarch on the inner disk, which often bears governmental symbols, while the outer disk is impressed with local information, in this case a scratched "N".

Objects like these lead cloth seals can provide valuable information to archaeologists. However, lead does not always survive well in the archaeological record. When lead deteriorates, unlike iron or copper, its original surface is not retained in the corrosion products. This means that no amount of cleaning can reveal the lost information. There is a chemical method which is sometimes successful in retrieving surface detail, but it is rarely used by conservators. This is because it permanently alters the chemical composition of a lead object and prevents future chemical analysis. In the case of these seals, it was determined that chemical intervention was appropriate as the information obtained from the surface decoration was more valuable than the material composition of the lead from which the objects are made. Fortunately, it was possible to recover the images visible on these two lead seals and with further research add to the archaeologists’ knowledge of the Angelica Knoll site.

| References |

|

| Adams, Diane L. |

| 1989 |

Lead Seals for Fort Michilimackinac, 1715-1781. Archaeological Completion Report Series #14., Mackinac State Historic Parks, Mackinac Island, MI. |

|

| Egan, Geoff |

| 1994 |

Lead Cloth Seals and Related Items in the British Museum. [with Mike Cowell and HeroGranger Taylor]. British Museum Occasional Paper #93., British Museum Press, London. |

|

| Endrei, W. and Egan, G. |

| 1982 |

The sealing of cloth in Europe, with special reference to the English evidence. Textile History13. |

|

| Luckenbach, Al and Cox, C. Jane |

| 2003 |

17th century lead cloth seals from Anne Arundel County, Maryland. Maryland Archaeology, Vol. 39. |

|