The Inkhorn

February 2012

By Patricia Samford, MAC Lab Director

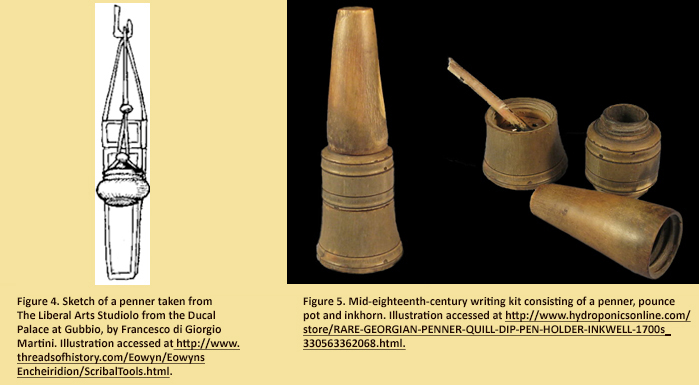

While sorting English earthenwares from a nineteenth-century privy in Baltimore, a staff member at the Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab discovered an unusual carved ivory object (Figure 1). No one at the lab had ever seen anything quite like it. Jump forward several months and sharp-eyed curator Sara Rivers-Cofield, never one to forget an object, spotted a similar item in an early nineteenth-century French peddler's catalog in the Winterthur Museum Library. Unfortunately, objects in the catalog were not labeled, since presumably everyone ordering from it would already know what all the items were! A little further digging, however, revealed that the object was part of a traveling writing kit.

While sorting English earthenwares from a nineteenth-century privy in Baltimore, a staff member at the Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab discovered an unusual carved ivory object (Figure 1). No one at the lab had ever seen anything quite like it. Jump forward several months and sharp-eyed curator Sara Rivers-Cofield, never one to forget an object, spotted a similar item in an early nineteenth-century French peddler's catalog in the Winterthur Museum Library. Unfortunately, objects in the catalog were not labeled, since presumably everyone ordering from it would already know what all the items were! A little further digging, however, revealed that the object was part of a traveling writing kit.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines penner as "a case or sheath for pens, of metal, horn, leather, etc., formerly carried at the girdle, often together with an inkhorn". The earliest citation for the use of the term is Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales, from about 1386, although there is evidence they were in use as early as the twelfth century (Scribal Tools 2011). In addition to the case for carrying pens, these kits also included one or two small containers for holding ink and pounce (sand used to dry the inked pages). The carved object from Baltimore appears to have been the part of the kit known as the inkhorn.

A dark residue resembling dried ink is adhered to the interior bottom and lower sides of the inkhorn and it is stained in several places along the interior lip, suggesting that excess ink was removed from pens by wiping the quills along the edge. The base of the inkhorn is plugged with a separate carved ivory disk; close examination reveals the seal to be watertight (Figure 2).

A dark residue resembling dried ink is adhered to the interior bottom and lower sides of the inkhorn and it is stained in several places along the interior lip, suggesting that excess ink was removed from pens by wiping the quills along the edge. The base of the inkhorn is plugged with a separate carved ivory disk; close examination reveals the seal to be watertight (Figure 2).

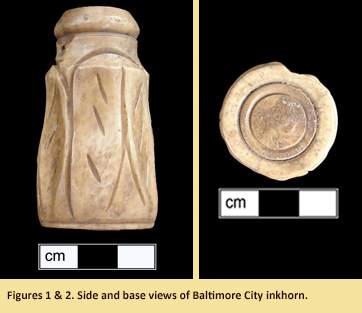

Fifteenth- and sixteenth-century paintings and prints depicting writing kits usually show the kit components held together with a cord and hung at the waist, with the inkhorn on one side of the belt and the penner along the other (Figure 3). There is a small (1 mm diameter) hole underneath the carved lip of the Baltimore inkhorn. This hole may have been used for attaching the cord that held the components of the penner together, similar to this sketch (Figure 4) created from the c. 1480 trompe l’oeil marquetry in the The Liberal Arts Studiolo from the Ducal Palace at Gubbio, by Francesco di Giorgio Martini (Metropolitan Museum of Art). The components of surviving eighteenth- and nineteenth-century kits usually fit together into a long cylinder (Figure 5).

The interior lip of the inkhorn does not have any threads, indicating that it was closed by plugging, perhaps with the pen case. Damage along the interior of the lip supports this conclusion.

Although we solved the mystery of the function of this interesting artifact, the question of who owned it still remains.