Go Figure!

May 2013

By Nichole Doub, MAC Lab Head Conservator

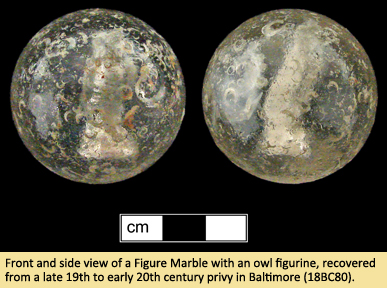

The history of marbles goes back thousands of years when the manufacture of these toys was as basic as rolling clay into small spheres. Through the centuries and across civilizations, the materials and production of marbles have become increasingly advanced, but none as exemplary as Figure Marbles, also known as Sulphide Marbles. These children’s toys consist of a large glass sphere, typically clear, with a porcelain figurine suspended in the center. Early collectors mistakenly believed that the figure was made of sulfur and the term persists to this day.

The history of marbles goes back thousands of years when the manufacture of these toys was as basic as rolling clay into small spheres. Through the centuries and across civilizations, the materials and production of marbles have become increasingly advanced, but none as exemplary as Figure Marbles, also known as Sulphide Marbles. These children’s toys consist of a large glass sphere, typically clear, with a porcelain figurine suspended in the center. Early collectors mistakenly believed that the figure was made of sulfur and the term persists to this day.

Figure Marbles are a type of glass marble originally produced in Lauscha, Germany from the mid 19th century until 1936 (American Toy Marble Museum 2013). The figure inside is most often an animal but can also be human or religious in nature. The figures are made in a mold and fired at high temperatures. Porcelain is capable of being heated to the same temperatures as molten glass, approximately 1000 degrees Celsius, which is important in the production of these marbles (Freestone 1991).

There are two methods of producing Figure Marbles. The first method uses a glass rod, heated at one end. The pre-heated figuring is then pressed in the soft, heated end and marble shears are used to shape the marble as the glass is folded around the figure. For the second method, a small blob of molten glass is placed at the end of an iron rod or “punty”, on which the heated figure is attached and then glass is folded around the figure (Block and Payne 2001: 9). If there is too great a difference between the temperature of the figure and the glass, either the figure can crack upon insertion in to the glass or the marble itself could shatter. Completed marbles are placed in an annealing chamber to slowly cool the marbles and prevent breakage.

The preservation of these objects varies. Those maintained by collectors tend to be in pristine condition, whereas marbles recovered from archaeological contexts often have a deteriorated surface, making the figure inside difficult to view. Some of this damage may have occurred during manufacture; the buffing process often opened air pockets produced during the glass folding (Chervenka 1994). Other damage may have been caused by use, the chipping of the surface as one marble struck another in play or in transport. And still further damage may have be a result of the burial environment.

The preservation of these objects varies. Those maintained by collectors tend to be in pristine condition, whereas marbles recovered from archaeological contexts often have a deteriorated surface, making the figure inside difficult to view. Some of this damage may have occurred during manufacture; the buffing process often opened air pockets produced during the glass folding (Chervenka 1994). Other damage may have been caused by use, the chipping of the surface as one marble struck another in play or in transport. And still further damage may have be a result of the burial environment.

It is a common misconception that glass is a stable material. However, not all glass is alike and there are many chemical variations, especially when colors are added. Silica is the primary component in glass, but unlike in quartz and flint where it is a strictly crystalline structure, the quick cooling of molten silica creates a random three-dimensional structure that creates an array of unpredictable properties. Depending on the composition of glass, an object may be susceptible to moisture, salts and weathering. When glass is exposed to moisture, as in a burial environment, ions are leached away creating weakened layers in the surface of the object (Cronyn 1990: 130). These layers can delaminate with the formation of salts or through stresses caused by cycles of shrinking and expanding in response to environmental conditions. This is responsible for the dull/iridescent/opaque surfaces found in many archaeological glass objects.

| References |

|

| American Toy Marble Museum |

| n.d. |

Retrieved from www.americantoymarbles.com/glossary.htm |

|

| Block, S.A and Payne, M.E. |

| 2001 |

Sulfide Marbles. Schiffer Publishing Ltd., Atglen, Pennsylvania. |

|

| Cronyn, J. M. |

| 1990 |

The Elements of Archaeological Conservation. Routledge, London. |

|

| Freestone, I. |

| 1991 |

Looking into Glass. Science and the Past. British Museum Press, London. |

|