The Mystery of Stiegel-Type Glassware

October 2015

By Erin Wingfield, MAC Lab Collections Assistant

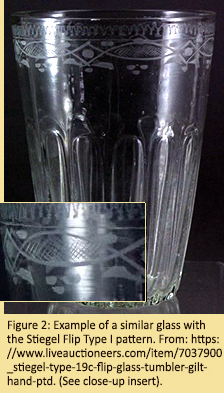

As often happens with archaeology, the smallest fragments can tell a much larger story. These engraved sherds of glass (Figure 1) were found at the Saunders Point Site (18AN39) in Anne Arundel County. The site consisted of one large cellar hole dating approximately to the 18th century. The fragments are decorated with simple shallow engraving, including a distinct oval shape with hatch marks through it. This pattern, listed by many as Stiegel Flip Type I (Figure 2), was identified by researcher and amateur archaeologist Frederick Hunter, who revived interest in the eccentric glass maker Henry Stiegel and his beautiful works (Daniel 1962:110).

As often happens with archaeology, the smallest fragments can tell a much larger story. These engraved sherds of glass (Figure 1) were found at the Saunders Point Site (18AN39) in Anne Arundel County. The site consisted of one large cellar hole dating approximately to the 18th century. The fragments are decorated with simple shallow engraving, including a distinct oval shape with hatch marks through it. This pattern, listed by many as Stiegel Flip Type I (Figure 2), was identified by researcher and amateur archaeologist Frederick Hunter, who revived interest in the eccentric glass maker Henry Stiegel and his beautiful works (Daniel 1962:110).

Henry Stiegel was born in Cologne, Germany in 1729. He travelled to Philadelphia in 1750, along with his mother and brother Andrew. Stiegel began his career as an assistant at the Elizabeth Iron Furnace and married the owner’s daughter. He gained control of the furnace after his father-in-law’s death and entered into a partnership with Charles Stedman (Knittle 1972:118-119). Stiegel became a successful ironmaster; however, he saw an opportunity to do more than his predecessor. Stiegel opened his first glassworks at Elizabeth Furnace in 1763, producing bottles and window glass (Knittle 1972:120). He soon became obsessed with making glassware rivaling the

Henry Stiegel was born in Cologne, Germany in 1729. He travelled to Philadelphia in 1750, along with his mother and brother Andrew. Stiegel began his career as an assistant at the Elizabeth Iron Furnace and married the owner’s daughter. He gained control of the furnace after his father-in-law’s death and entered into a partnership with Charles Stedman (Knittle 1972:118-119). Stiegel became a successful ironmaster; however, he saw an opportunity to do more than his predecessor. Stiegel opened his first glassworks at Elizabeth Furnace in 1763, producing bottles and window glass (Knittle 1972:120). He soon became obsessed with making glassware rivaling the  best works produced in England and Germany. In 1765, he began building his next glasshouse in Manheim, Pennsylvania (McKearin 1989:82). During construction, Stiegel withdrew large funds from his iron forge and travelled to Europe. Records show he hired skilled workers from England, Ireland, Italy, Germany and Bohemia, then shipped them and their families to Pennsylvania (Daniel 1962:110).

best works produced in England and Germany. In 1765, he began building his next glasshouse in Manheim, Pennsylvania (McKearin 1989:82). During construction, Stiegel withdrew large funds from his iron forge and travelled to Europe. Records show he hired skilled workers from England, Ireland, Italy, Germany and Bohemia, then shipped them and their families to Pennsylvania (Daniel 1962:110).

With tensions heating up between the colonies and England, tariffs were raised on all imported goods. Stiegel saw this as a perfect opportunity to market his local glassware as an alternative to pieces produced in Europe (Watkins 1950:28). His glassware became so popular he had several shops and agents from Boston to Baltimore (McKearin 1989:84). One of the most-produced forms was flip glasses -- thin walled tumbler style glasses, sometimes fluted, and commonly decorated with engraving or colorful enamel designs. These were used for drinking flip, a mixture of rum, beer, molasses and eggs or cream which was then shaken and warmed by plunging a hot poker into the frothy drink (Hirsch 2014). Stiegel’s glasshouses also produced clear flint glass with enameled floral and animal designs as well as elaborate molded pieces of brightly colored amethyst and cobalt glass.

During his height, Stiegel built a large mansion in Manheim which he filled with imported luxury goods, as well as two castles or towers complete with cannon to announce his arrival (Figure 3). Stiegel  became well known for his extravagant parties and flashy appearance (Knittle 1972:125; Watkins 1950:29). Many believe his extravagant lifestyle is why he was given the unofficial title of Baron, most likely by his own workers and townspeople (McKearin 1989:82). Stiegel was also deeply religious. He preached his own sermons and gave a plot of land to the Zion Lutheran Church for 5 shillings and the yearly payment of one red rose to him or his descendants (Knittle 1972:130).

became well known for his extravagant parties and flashy appearance (Knittle 1972:125; Watkins 1950:29). Many believe his extravagant lifestyle is why he was given the unofficial title of Baron, most likely by his own workers and townspeople (McKearin 1989:82). Stiegel was also deeply religious. He preached his own sermons and gave a plot of land to the Zion Lutheran Church for 5 shillings and the yearly payment of one red rose to him or his descendants (Knittle 1972:130).

As successful as Stiegel’s business appeared to be, his ambition to create the best glassware found him repeatedly taking out loans and increasing in debt. He borrowed or mortgaged one property to buy another until his dramatic rise to wealth came to a painful end (Knittle 1972:128-129). Even as the government foreclosed on his properties, Stiegel still believed he could turn his business around. The glassworks at Manheim was shut down in May of 1774, and by November, Siegel was arrested and placed in debtor’s prison. On Christmas Eve, the State Assembly made a special exemption releasing him from prison and debt but taking what was left of his property. His spirit broken, Stiegel spent the rest of his life living off the charity of friends and family. He moved in with his brother Andrew and then his nephew and spent his last days as a preacher and school teacher. Stiegel died in 1785, one day after Andrew. He was buried in an unmarked grave and faded into obscurity until, over a hundred years later, Frederick Hunter’s interest in glassware revived his story (Knittle 1972:132-134). In 1892, the Zion Lutheran Church revived the practice of presenting one red rose to the decedents of Stiegel every year as a remembrance and still continues the payment of the rose today (Watkins: 1950:30; Zion n.d.).

Unfortunately for collectors and researchers, identifying Stiegel-ware will always be a mystery. Stiegel never marked his pieces and was so successful replicating European styles and techniques that it is almost impossible to determine which pieces were produced at his glassworks (Watkins 1950:30). This has led to the use of the term Stiegel-Type when referring to pieces that fit the style and workmanship produced at the factory. Only one piece of stemware has ever been considered authentic, a commemorative wineglass (Figure 4) engraved for the wedding of Stiegel’s daughter (Corning Museum of Glass n.d.).

| References |

|

| Corning Museum of Glass |

| n.d. |

Commemorative Wineglass http://www.cmog.org/artwork/commemorative-wineglass-0. Corning Museum of Glass, accessed September 21, 2015. |

|

| Daniel, Dorothy |

| 1962 |

Cut & Engraved Glass 1771 – 1905. M. Barrows and Company, Inc., New York, NY. |

|

| Hirsch, Corin |

| 2014 |

5 Colonial-Era Drinks You Should Know. http://drinks.seriouseats.com/2014/04/colonial-era-drinks-cocktails-rum-flip-stonefence-syllabub-rattleskull.html, Serious Eats, accessed Sept. 18, 2015. |

|

| Knittle, Rhea Mansfield |

| 1972 |

Early American Glass. Garden City Publishing Co., Inc., Garden City, NY. |

|

| McKearin, Geroge S. and Helen |

| 1989 |

merican Glassmerican Glass. Crown Publishers, Inc., New York, NY. |

|

| Watkins, Lura Woodside |

| 1950 |

American Glass and Glassmaking. Cracker Barrel Press, Southampton, NY. |

|

| Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church |

| n.d. |

Festival of the Red Rose. http://www.zionmanheim.com/red-rose-festival.html, accessed Sept. 18, 2015. |

|