Ice Skating Through the Ages

December 2015

By Caitlin Shaffer, MAC Lab Conservator

As you lace up your ice skates this winter, you might be perfecting your triple lutz-toe loop combo, or you might just be trying to stay upright. In either case, you’re joining a long history of people taking to the ice for travel, sport, and leisure.

As you lace up your ice skates this winter, you might be perfecting your triple lutz-toe loop combo, or you might just be trying to stay upright. In either case, you’re joining a long history of people taking to the ice for travel, sport, and leisure.

Archaeological evidence shows that the earliest ice skates developed as a means of transportation in Northern Europe around 3,000 B.C. In a cold climate with a landscape full of waterways, skating was a simple, inexpensive, and very efficient way to travel over long distances or reach otherwise inaccessible areas for hunting (Formenti and Minetti 2007). These skates, usually made of cow or horse metatarsal bones, were fastened to the wearer’s shoes using leather straps. Because bones do not have an edge to push off of, forward motion was achieved by a long stick tipped with metal. This technology was clearly in use for quite some time, as William Fitz Stephen describes such a scene in 1773 London:

|

‘…when the great marsh…is frozen over, numerous

bands of young men go out to play on the ice.

They… fit leg-bones of animals to their feet,

binding them firmly around their ankles,

and hold in their hands poles shod with iron,

which they strike against the ice, and thus impel themselves on it with the swiftness of a bird…’

(N.A. 2015)

|

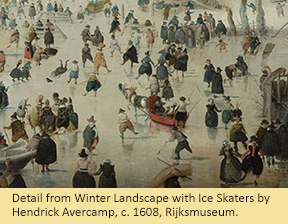

Bone skates gave way to wooden skates with metal runners by the 13th century. The sharper blade edge allowed skaters to propel themselves using just their leg muscles, while making it easier to turn and achieve faster speeds (Formenti and Minetti 2007). There is ample pictorial evidence that ice skating remained popular throughout the Middle Ages, and certainly during Europe’s Little Ice Age (Formenti and Minetti 2007). 18th and 19th-century ice skates saw further technical changes – longer blades and purpose-made boots, both of which increased the control of the skater. Modern day ice skates may look a little different from these earlier models, but the basic idea has remained essentially unchanged for hundreds of years.

Skating was an inclusive pastime from very early on. Prints and written records from as early as the 15th century indicate that activities on the ice were open to people of all ages, classes, and genders (Kestnbaum 2003). In colonial America, ice skating was commonplace, especially in New York, Delaware, and Pennsylvania, where settlers of Dutch and Swedish heritage kept up the traditions of their homelands (Struna 1996). Upon visiting New York in 1678, English clergyman Charles Wooley noted, “And upon the Ice it’s admirable to see Men & Women as it were flying upon their Skates from place to place, with Markets upon their Heads & Backs" (Gems et al. 2008). Americans continued ice skating in the 18th century, not just as a means of transport, but also for leisure. Alexander Graydon, a Philadelphia lawyer writes, “With respect to skating, though the Philadelphians have never reduced it to rules like the Londoners, nor connected it with their business like Dutchmen, I will yet hazard the opinion, that they were the best & most elegant skaters in the world” (Sarudy 2014). The opening of a skating pond in New York’s Central Park in the winter of 1858-59 provided ample opportunity for unchaperoned intermingling of men and women. Unsurprisingly, the pastime continued to grow in popularity into the 20th century, and it remains a favorite wintertime activity today.

Skating was an inclusive pastime from very early on. Prints and written records from as early as the 15th century indicate that activities on the ice were open to people of all ages, classes, and genders (Kestnbaum 2003). In colonial America, ice skating was commonplace, especially in New York, Delaware, and Pennsylvania, where settlers of Dutch and Swedish heritage kept up the traditions of their homelands (Struna 1996). Upon visiting New York in 1678, English clergyman Charles Wooley noted, “And upon the Ice it’s admirable to see Men & Women as it were flying upon their Skates from place to place, with Markets upon their Heads & Backs" (Gems et al. 2008). Americans continued ice skating in the 18th century, not just as a means of transport, but also for leisure. Alexander Graydon, a Philadelphia lawyer writes, “With respect to skating, though the Philadelphians have never reduced it to rules like the Londoners, nor connected it with their business like Dutchmen, I will yet hazard the opinion, that they were the best & most elegant skaters in the world” (Sarudy 2014). The opening of a skating pond in New York’s Central Park in the winter of 1858-59 provided ample opportunity for unchaperoned intermingling of men and women. Unsurprisingly, the pastime continued to grow in popularity into the 20th century, and it remains a favorite wintertime activity today.

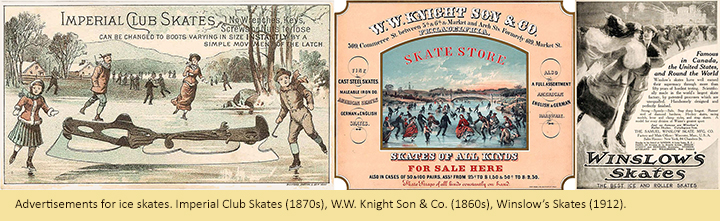

This pair of steel blade ice skates, dating to the late 19th or early 20th century, was recovered from archaeological investigations at the Stoll-Heisel Blacksmith Shop in St. George’s, Delaware. The business, destroyed by fire in 1919, did work as a blacksmith, wheelwright, and repair shop (Burrow et al. 2012). The site report notes, ‘A pair of ice skates… may have either just been sharpened and were awaiting pickup or had been dropped off at the shop shortly before it burned down. Since the fire happened in November or December someone may have had to quickly buy new skates for the upcoming ice skating season’ (Burrow et al. 2012). If the owner did purchase a new pair, there was no shortage of advertisers promising easy elegance and a heartwarming time on the ice – and who wouldn’t want to experience just that?

This pair of steel blade ice skates, dating to the late 19th or early 20th century, was recovered from archaeological investigations at the Stoll-Heisel Blacksmith Shop in St. George’s, Delaware. The business, destroyed by fire in 1919, did work as a blacksmith, wheelwright, and repair shop (Burrow et al. 2012). The site report notes, ‘A pair of ice skates… may have either just been sharpened and were awaiting pickup or had been dropped off at the shop shortly before it burned down. Since the fire happened in November or December someone may have had to quickly buy new skates for the upcoming ice skating season’ (Burrow et al. 2012). If the owner did purchase a new pair, there was no shortage of advertisers promising easy elegance and a heartwarming time on the ice – and who wouldn’t want to experience just that?

| References |

|

| Burrow, Ian, Alison Haley, Patrick Harshbarger and William Liebeknecht |

| 2017 |

The Small-Town Blacksmith in an Industrializing World: The Stoll/Heisel Blacksmith Shop (1852-1919) 204 North Main Street St. Georges, Red Lion Hundred Newcastle County, Delaware. Report prepared for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Philadelphia, PA. |

|

| Formenti, Frederico and Alberto E. Minetti |

| 2007 |

Human Locomotion on Ice: The Evolution of Ice-skating Energetics Through History. The Journal of Experimental Biology(210): 1825-1833. |

|

| Gems, Gerald, Linda Borish and Gertrud Pfister |

| 2008 |

Sports in American History from Colonization to Globalization. Chicago: Human Kinetics. |

|

| Kestnbaum, Ellyn |

| 2003 |

Culture on Ice: Figure Skating & Cultural Meaning. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. |

|

| N.A. |

| 2015 |

Find Spotlight: The Art of Medieval Ice Skating. https://ulasnews.wordpress.com/2015/02/02/find-spotlight-the-art-of-medieval-ice-skating/, accessed November 18, 2015. |

|

| Sarudy, Barbara Wells |

| 2014 |

How 17C Colonial American Women Came to Ice Skate - From Europe to England to Colonial America. www.b-womeninamericanhistory17.blogspot.com/2014/02/how-17c-colonial-american-women-came-to.html, accessed November 19, 2015. |

|

| Struna, Nancy L. |

| 1996 |

People of Prowess: Sport, Leisure and Labor in Early Anglo-America. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. |

|