Curator's Choice 2019

A Tisket, a Tasket, a Beaded Wire Basket

March 2019

By Sara Rivers Cofield, Curator of Federal Collections

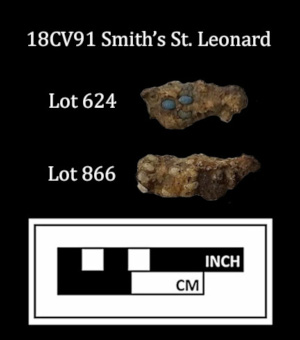

Figure 1: Iron fragments wrapped in tiny blue

Figure 1: Iron fragments wrapped in tiny blue

beads (top) and white beads (bottom).

Each bead is about 1.2 mm wide.Last year JPPM's Public Archaeology crew brought me two little pieces of iron with glass seed beads embedded in the corrosion (Figure 1). They wanted to know if the beads were just accidentally stuck in the corrosion because they were deposited next to the metal, or was something else going on? My answer was that something else was going on.

Back in 2011 I wrote a Curator's Choice about metallic threads recovered at the JPPM Public Archaeology site, Smith's St. Leonard, and a 17th-century site known as Charles' Gift (Rivers Cofield 2011). Metallic thread embroidery was incredibly popular in the 17th and 18th centuries on gloves, gowns, coats, waistcoats, shoes, etc. It was also popular for a kind of three-dimensional embroidery known as stump work, which decorated caskets, boxes, mirror frames, and pieces of art meant to hang like paintings. Sometimes tiny beads were incorporated into the embroidery. Having studied this needlework while researching metallic thread, I had seen images of a related art form worked in beads: that of the 17th-century beaded wire basket (Figures 2-3). So when the crew brought me iron with white and blue beads surrounding it in a seeming spiral pattern, I pulled the embroidery book where I remembered seeing the beaded basket, and showed them what I thought this represented (Brooke 1992:92). Sometimes when I identify something like this, especially so quickly, it surprises people. But I ask you, if you had seen images of these beaded baskets, wouldn't you have remembered them? They seem pretty unforgettable to me!

Figure 2: Beadwork, ca. 1680 (21"x18"x5.5")

Figure 2: Beadwork, ca. 1680 (21"x18"x5.5")

recently sold by Sotheby's (Lot 1402).These baskets, which became popular in the second half of the 17th century, have sometimes been interpreted as gift baskets because of their similarity in form to silver baskets used for offering Christening clothes to newborns. They seem too impractical to have held much though. Since these baskets often depict commemorative scenes, such as royal couples, it has also been suggested that they were used as betrothal or wedding gifts.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met 2019) interprets the baskets as a possible expression of clever marketing on the part of haberdashers, merchants, and bead and wire traders who wished to capitalize on society's appetite for exotic new beads entering England after the 1630s. While some suggest that affluent girls and women made these baskets as a pastime that showed off their artistic talents (The Holbourne Museum 2019), it is also possible that the baskets were sold in kits or made by professionals (The Met 2019). Whatever their origin, they are certainly works of art that were meant to be displayed and admired.

Figure 3: Beadwork basket, dated 1662 (18.5"x13.5"x7")

Figure 3: Beadwork basket, dated 1662 (18.5"x13.5"x7")

sold by Sotheby's on January 20, 2019 (Lot 1404).To me, this is the kind of artifact that challenges stereotypes of early American colonists as people who were living off the land, spending all their time farming, and owning only those goods that fulfilled practical needs. That view of American colonists may be born out of the romanticized tale of the 19thcentury American homesteader imposed on centuries past. Or perhaps it is just incredulity that people "back then" could have possibly had such things in Maryland. It can be hard to imagine how people executed such tiny hand work in the pre-industrial era.

However, the ability to make and own such impractical items was one of the hallmarks of the classconscious English culture of the 17th and 18th centuries. The Smith family who lived at the site from ca. 1711-1754 were not spending every waking hour cultivating tobacco or boiling laundry. The laborintensive tasks of maintaining a profitable plantation and household were completed by at least 45 enslaved persons who were held in bondage at Smith's St. Leonard. That allowed the Smith family plenty of time and money to make or purchase items whose value was in the aesthetic statements they made.

Despite the fineness of such a piece, it is fairly easy to understand how fragments of a beaded basket ended up in the midden heap at some point before Smith's St. Leonard was abandoned ca. 1754. The popularity of these baskets peaked in the third quarter of the 17th century, which meant they would have been a somewhat outdated by the time the site was first occupied (ca. 1711). Even if the Smiths wanted to keep the old-fashioned basket for sentimental reasons, the humid environment of the plantation on St. Leonard Creek would have promoted unattractive rust on the wire frame. Such an item could be easily broken and impractical to reuse. That was bad news for the basket, but great news for archaeology, as the discovery of these two tiny iron fragments wrapped in white and blue beads contribute to our understanding of artwork that was present on early 18th-century tobacco plantations in Maryland.