Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory

Main_Content

Curator's Choice 2019

An 18th-century French Caribbean Coin in Baltimore

October 2019

By Rebecca Morehouse, State Curator

In the years before the American Revolution and the establishment of a federal mint, the North American colonies relied on foreign coins for their primary currency. With control over colonial trade and manufacturing in the hands of Britain, a country without access to major sources of precious metals and with no gold or silver to be mined in eastern North America, colonists turned to coinage from other countries (Lasser et al. 1997: 1). Spanish silver and gold pieces were obtained through trade with the southern Spanish Latin American colonies and were predominantly used by wealthy colonists for large transactions and the import of goods (Smoak 2017: 472). The poor and middling colonists, as well as the enslaved, relied more on coins of a smaller denomination to conduct commerce (Kelleher 2016: 49).

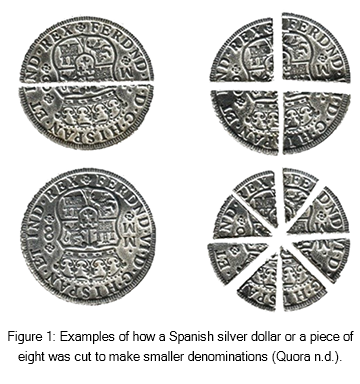

As in North America, colonies in the Caribbean also struggled to provide sufficient currency for use in towns and on plantations. Goods such as tobacco, rum, and sugar were often used as a form of currency but the Caribbean islanders also found other innovative ways to deal with the lack of coinage, such as cutting Spanish silver coins into more usable pieces, or counterstamping coins for use in a specific colony (Salamanca-Heyman 2004: 57; Kelleher 2016: 50). The most common silver coin was the Spanish dollar, also called a “Piece of Eight” from the way it was cut into 8 pie-shaped wedges (Figure 1). Counterstamping was the act of applying a stamp to a coin to change its value and/or to indicate it would be accepted as legal tender in a place other than where it was originally issued (Doty 1982: 75). Various types of European coins of small denomination were counterstamped for use in several of the Caribbean colonies.

While the Spanish dollar was recognized as a global currency in the early colonial period, as Spanish power waned and Britain, France and the Netherlands competed to dominate in the Caribbean colonies, large volumes of diverse foreign coins found their way into circulation. Some of the most common coins in use along with the dollar were underweight Portuguese-Brazilian gold coins known as “Joes”, Spanish two-reales, and stamped French copper coins known as “black dogs” or “stampees” (Kelleher 2016: 50; Smoak 2017: 472). This coinage, particularly the small counterstamped copper coins, was primarily used by enslaved individuals. Foreign coinage was critical to economic life in the Caribbean colonies for people across the social spectrum (Smoak 2017: 472).

Occasionally, coinage from the Caribbean would find its way to the North American colonies, perhaps in the pocket of a sailor or an enslaved individual who was being transferred for sale. One such coin, with a “TB/o” counterstamp for use in the colony of Tobago, was recovered from a small midden feature during excavations at Brown’s Wharf in the Fells Point Historic District in Baltimore City (Figure 2). The Baltimore Center for Urban Archaeology monitored and tested the site during redevelopment along Thames Street in the late 1980s.

This coin began its life in 1749 as a French 2 sols and was likely used as small change in France for many years before being selected for official use in the French Caribbean colonies (Smoak 2017: 474). The coin received a crowned “C” stamp on the reverse to mark it for official use and “TB/o” on the obverse for use specifically in Tobago (Krause et al.1998: 236). The legend “SIT NOM DOM H BENEDICTUM,” translated “Blessed be the name of the Lord”, along with the date 1749, can still be partially seen surrounding the counterstamp on the reverse. A faint shadow of a “C” is all that remains on the reverse side. The reverse legend “LUD XV D G FR ET NAV REX,” translated “Louis XV, by the grace of God, King of France and of Navarre,” is completely worn away. The coin in Figure 3 is an example in much better condition

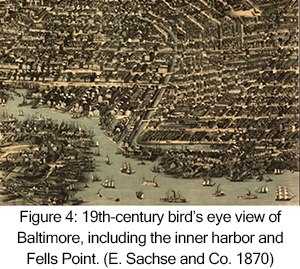

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Brown’s Wharf was the home of affluent residents and tradesmen such as sea captains, ship joiners (builders), and ship chandlers (dealer in supplies and equipment for ships). It was a center for importing, exporting, and storing goods from around the world, including sugar, coffee, indigo, tobacco, and cocoa from the Caribbean and Central and South America, as well as linen, shirts, hats, shoe insoles,

and other clothing items from Europe (Figure 4) (Stevens 1989: 6). Enslaved persons were also listed among the cargo of many ships that docked at the Fells Point wharves (Arnett 1975).

It’s not difficult to imagine this small French Caribbean coin dropping from the pocket of a dock worker, a sailor, of perhaps even an enslaved individual being transferred to Baltimore from the Caribbean for sale, only for it to be excavated by archaeologists over 200 years later.

References |

|

Arnett, Earl

|

| 1975 |

“Fells Point Tour Includes One of the Oldest Warehouses” Baltimore Sun. March 19, 1975. Web resource: https://www.newspapers.com/image accessed 23 September 2019.

|

|

Doty, Richard G.

|

| 1982 |

The Macmillan Encyclopedic Dictionary of Numismatics. New York, New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.

|

|

East Rock Coins

|

| n.d. |

Web resource: https://www.eastrockcoins.com/product/black-dogg-tobago-countermark-vlack-444 accessed 23 September 2019.

|

| |

| E. Sachse and Co. |

| 1870 |

E. Sachse and Co.’s bird’s eye view of the city of Baltimore, 1869. Map. Web resource: https://www.loc.gov/item/75694535/ accessed 23 September 2019. |

| |

| Kelleher, Dr. Richard |

| 2016 |

“Coins of the Tudors and Stuarts: Colonial Money in North American and the Caribbean”. Web resource: https://www.academia.edu/33455470/Coinage_of_Colonial_North_America_and_the

_Caribbean accessed 23 September 2019.

|

| |

| Krause, Chester L., Clifford Mishler, and Colin R. Bruce II, ed. |

| 1998 |

Standard Catalog of World Coins: 18th Century Edition 1701-1800. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. |

| |

|

| Lassar, Joseph R., Gail G. Greve, William E. Pittman, and John A. Caramia, Jr. |

| 1997 |

The Coins of Colonial America: World Trade Coins of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Williamsburg, Virginia. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. |

| |

|

| Quora |

| n.d. |

Web resource: https://www.quora.com/Which-was-the-currency-most-used-for-commercial-exchange-in-the-sixteenth-seventeenth-eighteenth-and-nineteenth-centuries-as-is-the-US-dollar-now. accessed 23 September 2019. |

| |

|

| Salamanca-Heyman, Maria Fernanda |

| 2004 |

“St. Eustatius and the Caribbean Trade System: A Study of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Coins from the Caribbean”. Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects at William and Mary W & M ScholarWorks. Paper 1539626445. |

| |

|

| Smoak, Katherine |

| 2017 |

“The Weight of Necessity: Counterfeit Coins in the British Atlantic World, circa 1760-1800”. William and Mary Quarterly 74(3): 467-502. |

| |

|

| Stevens, Kristen L. |

| 1989 |

An Investigation of the Archaeological Resources Associated with the Brown’s Wharf Site (18BC59) on Thames Street, Baltimore, Maryland. Baltimore Center Urban Archaeology Research Series No. 28. |

| |

|

| |

|