Copper Points from the Posey Site

June 2009

By Sara Rivers Cofield, MAC Lab Federal Curator

The Posey site is a circa 1650 to 1680 settlement that was probably the year-round home of a few American Indian families (Harmon 1999). Although not a large village, the Posey site affords archaeologists

the opportunity to study how interaction with European colonists changed the material culture of Maryland's Indians in the 17th century.

The Posey site is a circa 1650 to 1680 settlement that was probably the year-round home of a few American Indian families (Harmon 1999). Although not a large village, the Posey site affords archaeologists

the opportunity to study how interaction with European colonists changed the material culture of Maryland's Indians in the 17th century.

Artifacts recovered at the Posey site indicate that pottery and shell beads were being made there for personal use, and possibly also as goods for trade with the Europeans who lived in the surrounding area.

The families who lived at the Posey site had access to a global trade network when interacting with the colonists. Stoneware ceramics from Germany, glass beads from Italy, tin-glazed ceramics from the

Netherlands, and utilitarian ceramics from England were regularly shipped to Maryland by the 1650s, and these types of artifacts were recovered at the Posey site. Though Posey's inhabitants certainly

did not abandon their traditional practices of pottery-making, shell bead work, and stone-tool usage, the introduction of European goods expanded the range of materials they could incorporate into these

practices. For example, metal tools could be used to drill the tiny holes needed for shell beads, and decorations might be applied to clay pipes with metal stamps (Harmon 1999).

The most striking example of material culture change at Posey, however, is the appearance of projectile points made from copper as opposed to stone. Chesapeake Indians had access to natural copper traded

from areas such as the Great Lakes and western North Carolina long before they could obtain it from Europeans, but the amount of copper that could be obtained was limited, and it was generally reserved

for the adornment of society elites (Mallios and Emmett 2004). The special status of copper made it very desirable as a trade item, and Europeans quickly realized that they could trade their old copper

kettles and scrap copper for furs, food, and hospitality. As copper became more readily available, its special status with the Chesapeake Indians diminished, and its use for making utilitarian tools such

as points increased.

The most striking example of material culture change at Posey, however, is the appearance of projectile points made from copper as opposed to stone. Chesapeake Indians had access to natural copper traded

from areas such as the Great Lakes and western North Carolina long before they could obtain it from Europeans, but the amount of copper that could be obtained was limited, and it was generally reserved

for the adornment of society elites (Mallios and Emmett 2004). The special status of copper made it very desirable as a trade item, and Europeans quickly realized that they could trade their old copper

kettles and scrap copper for furs, food, and hospitality. As copper became more readily available, its special status with the Chesapeake Indians diminished, and its use for making utilitarian tools such

as points increased.

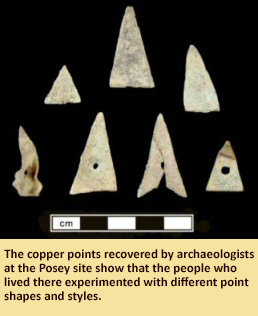

The variety of copper point types recovered at the Posey site indicates that there was some experimentation going on in terms of how best to make copper sheets or scraps into points. In one case, two scrap

fragments were folded over each other to make a barbed point. Other points were made by snipping sheet copper into isosceles triangles or small equilateral triangles. Some of the points have holes in

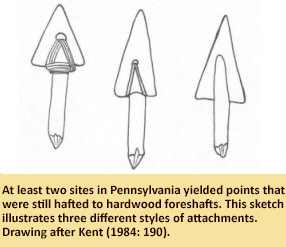

them while others do not. Archaeological examples from Pennsylvania indicate that once completed, these copper points were probably attached to hardwood arrow foreshafts with fine sinew and glue,

though the possibility that they were used to decorate clothing or other goods cannot be ruled out (Kent 1984). It is unclear whether hafted points were strictly utilitarian and available to all, or

if they carried on the tradition of special status afforded to copper, and were used pirmarily by elites for certain purposes. What is clear, is that these points rose in popularity in the 17th century

and have been found at numerous sites that date into the 18th century (Curry n.d.; Kent 1984).

The variety of copper point types recovered at the Posey site indicates that there was some experimentation going on in terms of how best to make copper sheets or scraps into points. In one case, two scrap

fragments were folded over each other to make a barbed point. Other points were made by snipping sheet copper into isosceles triangles or small equilateral triangles. Some of the points have holes in

them while others do not. Archaeological examples from Pennsylvania indicate that once completed, these copper points were probably attached to hardwood arrow foreshafts with fine sinew and glue,

though the possibility that they were used to decorate clothing or other goods cannot be ruled out (Kent 1984). It is unclear whether hafted points were strictly utilitarian and available to all, or

if they carried on the tradition of special status afforded to copper, and were used pirmarily by elites for certain purposes. What is clear, is that these points rose in popularity in the 17th century

and have been found at numerous sites that date into the 18th century (Curry n.d.; Kent 1984).

For 12,000 years, Maryland's inhabitants had made tools from various kinds of stone, but the use of certain stone tools such as points and knives decreased as metal tools gradually replaced them after

European contact. The new trade goods marked the decline of one technological era in Maryland and the beginning of another. As interaction between Maryland's Indians and European colonists continued in the

late 17th and 18th century, another hunting tool increased in popularity among the Indian population at Posey and elsewhere; the firearm. But that is a story for another Curator’s Choice…

Photos Courtesy of Naval District Washington, Indian Head.

| References |

|

| Curry, Dennis C. |

| n |

| .d. |

"We have been with the Emperor of Piscataway, at his fort:" Archaeological Investigation of the Heater's Island Site (18FR72). Draft manuscript (in preparation), Maryland HIstorical Trust, Crownsville, Maryland. |

|

| Kent, Barry C. |

| 1984 |

Susquehanna's Indians. Anthropological Series Number 6. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. |

|

| Harmon, James M. |

| 1999 |

Archaeological Investigations at the Posey Site (18CH281) and 18CH282, Indian Head Division, Naval Surface Warfare Center,

Charles County, Maryland. Draft manuscript on file, Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory, Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum, St. Leonard. |

|

| Ma |

| llios, Seth, and Shane Emmett |

| 2004 |

Demand, Supply, and Elasticity in the Copper Trade at Early Jamestown. The Journal of the Jamestown Rediscovery Center, Vol. 2. |

|