A "Wellth" of History

October 2010

By Sami Allen, MAC Lab Public Archaeology Asst.

Located a mile east of the Potomac River and on the edge of a towering, steep bluff just outside the District of Columbia's border in Maryland lies an extraordinary archaeological site called Oxon Hill. Beginning in 1687 this area was home to John and Rebecca Addison and multiple generations succeeding them until 1810. This agricultural plantation was still occupied by many different owners until the early 20th century (Garrow & Wheaton 1986).

Located a mile east of the Potomac River and on the edge of a towering, steep bluff just outside the District of Columbia's border in Maryland lies an extraordinary archaeological site called Oxon Hill. Beginning in 1687 this area was home to John and Rebecca Addison and multiple generations succeeding them until 1810. This agricultural plantation was still occupied by many different owners until the early 20th century (Garrow & Wheaton 1986).

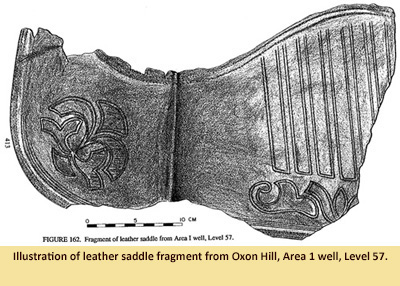

In 1985 archaeological investigations revealed a 13-meter-deep well that was deemed useless as a water-source in the early 18th century and served as a trash disposal thereafter. The area of the well below the water table is particularly exciting because it was here that a decorated leather saddle fragment was found among other well-preserved artifacts made of organic materials such as bone and wood. Based on ceramic and pipe stem analysis for the level (57) and section (C) where the saddle fragment was found, archaeologists believe the intact piece of leather dates to the mid-18th century (Garrow & Wheaton 1986).

The leather saddle fragment, which is on display at Jefferson Patterson Park & Museum's Visitor Center, was for the most part able to keep its original shape because of the presence of water and the lack of oxygen in its burial environment. The absence of oxygen prevented microbes and insects from surviving and assisting with the deterioration process. Over time, the leather itself has lost its natural cellular form but when soaked in water for over two centuries, the water acted as support to fill in the spaces of the leathers' cells and retain its shape (Personal communication with Nichole Doub).

The leather saddle fragment, which is on display at Jefferson Patterson Park & Museum's Visitor Center, was for the most part able to keep its original shape because of the presence of water and the lack of oxygen in its burial environment. The absence of oxygen prevented microbes and insects from surviving and assisting with the deterioration process. Over time, the leather itself has lost its natural cellular form but when soaked in water for over two centuries, the water acted as support to fill in the spaces of the leathers' cells and retain its shape (Personal communication with Nichole Doub).

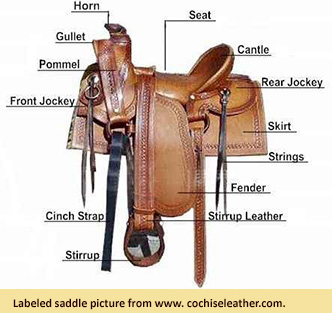

There is still much we need to learn about this intriguing saddle piece. For instance, what part of the original, complete saddle did this fragment come from? This can be hard to determine because so few saddles from the 18th century survive for comparison. The contour of the leather fragment appears to match the shape of the "rear jockey" from a 19th century saddle. Even though the Oxon Hill saddle is from an earlier century, saddles did not change drastically in that period of time (see the labeled picture from (www.cochiseleather.com) for an example). In fact, many of the saddles that we see today greatly resemble those of the 18th and 19th centuries (Personal communication with Sara Rivers-Cofield). "Jockeys cover the exposed upper sides of the saddle tree bars. The rear jockey in particular, covers and protects the 'fan,' the bar from the back of the cantle back towards the end of the saddle" (Beatie 1981).

There is still much we need to learn about this intriguing saddle piece. For instance, what part of the original, complete saddle did this fragment come from? This can be hard to determine because so few saddles from the 18th century survive for comparison. The contour of the leather fragment appears to match the shape of the "rear jockey" from a 19th century saddle. Even though the Oxon Hill saddle is from an earlier century, saddles did not change drastically in that period of time (see the labeled picture from (www.cochiseleather.com) for an example). In fact, many of the saddles that we see today greatly resemble those of the 18th and 19th centuries (Personal communication with Sara Rivers-Cofield). "Jockeys cover the exposed upper sides of the saddle tree bars. The rear jockey in particular, covers and protects the 'fan,' the bar from the back of the cantle back towards the end of the saddle" (Beatie 1981).  They serve as a decorative cover-up instead of bearing the weight of the rider which may explain why there is not much surface damage or wear to the Oxon Hill fragment. No other saddle fragments have been identified in the Oxon Hill well, but that makes sense if this fragment was a rear jockey because rear jockeys tended to be a separate piece from the whole saddle and were connected by leather ties or a leather connector plate (Beatie 1981). The piece may not have been connected to the whole saddle when it was discarded.

They serve as a decorative cover-up instead of bearing the weight of the rider which may explain why there is not much surface damage or wear to the Oxon Hill fragment. No other saddle fragments have been identified in the Oxon Hill well, but that makes sense if this fragment was a rear jockey because rear jockeys tended to be a separate piece from the whole saddle and were connected by leather ties or a leather connector plate (Beatie 1981). The piece may not have been connected to the whole saddle when it was discarded.

Historically, saddles were a symbol of status, and they could be plain, slightly decorative, or "embellished with elaborate leather work and embroidery with precious metals and jewels" (www.cochiseleather.com). After John's son, Thomas Addison, died in 1727 a probate inventory of his belongings listed "3 Mens Old Saddles, 1 Womans" as being worth one pound, which is surprisingly modest considering how wealthy the Addison's were. The recovered Oxon Hill fragment may very well match up with one of the saddles mentioned. The distinction between men's saddles and women's saddles at this time had to do with the women riding side-saddle – on saddles designed to support both of the women's legs on one side of the horse. It is unknown whether the "rear jockey" fragment was part of a man or woman’s saddle.

And there are still more questions to be answered. Where did the design on the leather originate and does the pattern have any significance? Also, were any of the unidentifiable wood or iron fragments found in the same level of the well a part of the saddle-tree that would have formed the saddle's underlying structure? Despite these unanswered questions, a 250-year old leather saddle fragment has survived the natural decaying process which is, in itself, incredible!

| References |

|

| Beatie, Russel H. |

| 1981 |

Saddles. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Publishing Division of the University. Chapter 15: 119-121. U.S. |

|

| Cochise Leather Company |

| 2010 |

The History of Western Leather Spurs, and Spur Straps, Cuffs, Chaps, Chinks and Saddles. http://www.cochiseleather.com/leather-history.aspx. |

|

| Doub, Nichole |

| 2010 |

Personal Communication – Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory. |

|

| Garrow, Patrick H.; Wheaton, Jr., Thomas R. |

| 1986 |

Oxon Hill Manor Archaeological Site Mitigation Project I-95/MD 210/I-295, Volume 1. Garrow and Associates, Inc., Atlanta, Georgia. |

|

| Rivers-Cofield, Sara |

| 2010 |

Personal communication – Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory. |

|