Curator's Choice 2010

Sacred Silver: A Cross-Shaped Reliquary Pendant

December 2010

By Sara Rivers Cofield, MAC Lab Curator of Federal Collections

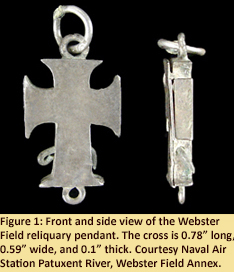

A reliquary is something that is designed to hold a sacred relic, such as a piece of the True Cross or a saint's bone. Anything that has been in contact with Christ or the saints could qualify as a sacred relic. Some relics are kept in chests or other large containers, while others are very small and fit into a pendant that can be worn close to the heart. One such reliquary pendant was discovered by archaeologists in St. Inigoes, Maryland aboard the Naval Air Station Patuxent River's Webster Field Annex (Figure 1).

A reliquary is something that is designed to hold a sacred relic, such as a piece of the True Cross or a saint's bone. Anything that has been in contact with Christ or the saints could qualify as a sacred relic. Some relics are kept in chests or other large containers, while others are very small and fit into a pendant that can be worn close to the heart. One such reliquary pendant was discovered by archaeologists in St. Inigoes, Maryland aboard the Naval Air Station Patuxent River's Webster Field Annex (Figure 1).

The Webster Field reliquary was probably lost by a resident of a Jesuit settlement that had existed at the site from circa 1637-1942. Initially, Jesuits established a plantation there to raise crops and support Jesuit missions, but after a 1689 uprising overthrew the Catholic Calvert family's control of Maryland, Protestants marginalized Maryland's Catholics by passing anti-Catholic Penal Laws, and the plantation at St. Inigoes became a private base of Jesuit operations. The reliquary was found in a soil layer that had been disturbed by the plow, but other artifacts found nearby primarily fall into the circa 1680-1750 date range, indicating that it probably dates to the period after 1689 when St. Inigoes was an important home base for clergy who rode out on horseback to offer Mass services and hear confessions in small chapels and private homes (Schroth 2007:26; Sperling and Galke 2001).

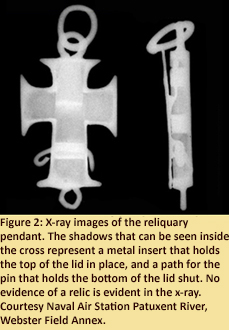

The practice of wearing a reliquary pendant has been popular since the 14th century (Thunø 2002:14). Most of the examples that survive in museums have enameled decoration, inset jewels, or carved images, as well as built-in hinges so that they can open and close with ease. The Webster Field cross is more modest. Although it is made primarily of silver and it has a loop at the bottom for a bauble that might have dressed it up a bit, there is no decoration, no silversmith's mark, and the lid is held in place by an unsightly asymmetric pin that prevents archaeologists from opening the pendant without damaging it. An x-ray taken to see if it had anything inside revealed only the internal structure of the cross; there is no evidence of the relic it once held (Figure 2).

The practice of wearing a reliquary pendant has been popular since the 14th century (Thunø 2002:14). Most of the examples that survive in museums have enameled decoration, inset jewels, or carved images, as well as built-in hinges so that they can open and close with ease. The Webster Field cross is more modest. Although it is made primarily of silver and it has a loop at the bottom for a bauble that might have dressed it up a bit, there is no decoration, no silversmith's mark, and the lid is held in place by an unsightly asymmetric pin that prevents archaeologists from opening the pendant without damaging it. An x-ray taken to see if it had anything inside revealed only the internal structure of the cross; there is no evidence of the relic it once held (Figure 2).

Despite its simplicity, this artifact was probably extremely important to its owner. Sacred relics were associated with miraculous powers, including healing properties. Catholics often wore sacred relics as a form of protection, which might be particularly desirable to colonists facing unknown perils overseas. At least two reliquaries have been recorded in Maryland's early history. One is a gold reliquary case listed in the 1647 probate inventory of Maryland's first Governor, Leonard Calvert (Archives of Maryland 1887:321). The other belonged to Father Andrew White, one of the Jesuits who arrived with the first wave of Maryland colonists (Figure 3). The 1642 annual letter from Maryland Jesuits to Rome states that Father White used his reliquary to heal an Indian who was speared in an ambush. White applied "to the wound on each side the sacred relic of the Most Holy Cross, which he carried in a case around his neck," and the man miraculously recovered by the next day (Curran 1988:70-71). A reliquary pendant therefore acted as both a symbol of one's faith and a protection against harm. Such an object might have become even more desirable when Catholics were oppressed after 1689. A small pendant could be easily concealed under one's clothing, offering the comfort and security of belief in its power without fear of persecution.

| References |

|

| Archives of Maryland |

| 1887 |

Volume IV: Judicial and Testamentary Business of the Provincial Court 1637-1650. Edited by William Hand Brown. Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society. |

|

| Curran, Robert Emmett, ed. |

| 1988 |

American Jesuit Spirituality: The Maryland Tradition, 1634-1900. New York: Paulist Press. |

|

| Schroth, Raymond A. |

| 2007 |

The American Jesuits: A History. New York: New York University Press. |

|

| Sperling, Christopher I., and Laura J. Galke |

| 2001 |

Phase II Archaeological Investigations of 18ST233 and 18ST329 Aboard Webster Field Annex, Naval Air Station, Patuxent River, St. Mary's County, Maryland. Report prepared for the Department of Public Works, Naval Air Station, Patuxent River. Manuscript on file, Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory, Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum, St. Leonard. |

|

| Tanner, Mathias |

| 1694 |

Societas Jesu apostolorum imitatrix Prague: Typis Universitatis Carolo-Ferdinandeae. Special Collections Division, Georgetown University Library. Accessed online November 17, 2010 via the Library of Congress http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/religion/rel01-2.html. |

|

| Thunø, Erik |

| 2002 |

Image and Relic: Mediating the Sacred in Early Medieval Rome. Rome, Italy: L’erma Di Bretschneider. |

|