The Real Reason Maryland Fans Hate Duke

March 2011

By Edward Chaney, MAC Lab Deputy Director

The Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory has many artifacts that are interesting to us because of their rarity, or because they reflect the artistic or technical skill of their creators, or because they vividly illustrate past life, and we have used the Curator’s Choice project to bring them to the public’s attention. But one of the most seemingly mundane objects in our collection is also one of the most important, because it helped change the American economy.

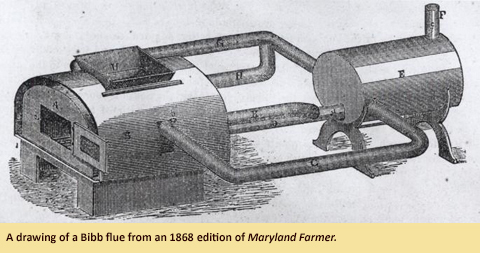

Historians tell us that tobacco cultivation formed the basis of social and economic life in the Upper Southern colonies from the earliest days of English settlement. And for 200 years, that tobacco was dried, or "cured," in open-air barns. Curing was one of the most important steps in producing a sellable crop; if it wasn't handled just right, the tobacco leaf could lose flavor, or even spoil. So in the early 19th c., some farmers began experimenting with using heat to ensure that the tobacco dried evenly. But they met with little success until 1861, when a Calvert County, MD., farmer and physician, George Dorsey, along with Bently Bibb and George Needham, patented a "Tobacco Curing Apparatus." Their device consisted of a wood- or coal-fired furnace and a series of heating pipes, or flues, that were placed in an air-tight barn. It was sold by Bently Bibb, who was a stove manufacturer.

Historians tell us that tobacco cultivation formed the basis of social and economic life in the Upper Southern colonies from the earliest days of English settlement. And for 200 years, that tobacco was dried, or "cured," in open-air barns. Curing was one of the most important steps in producing a sellable crop; if it wasn't handled just right, the tobacco leaf could lose flavor, or even spoil. So in the early 19th c., some farmers began experimenting with using heat to ensure that the tobacco dried evenly. But they met with little success until 1861, when a Calvert County, MD., farmer and physician, George Dorsey, along with Bently Bibb and George Needham, patented a "Tobacco Curing Apparatus." Their device consisted of a wood- or coal-fired furnace and a series of heating pipes, or flues, that were placed in an air-tight barn. It was sold by Bently Bibb, who was a stove manufacturer.

The Bibb flue apparatus was heavily hyped in agricultural publications as a revolutionary advance, but because it was quite expensive and difficult to operate, few Maryland tobacco farmers were willing to invest in one. The old technique -- air-curing -- made more sense for them. After a few years, farmers who had bought the Bibb flue were practically giving them away. Dorsey's apparatus, and flue-cured tobacco, quickly disappeared from the Maryland landscape.

The Bibb flue apparatus was heavily hyped in agricultural publications as a revolutionary advance, but because it was quite expensive and difficult to operate, few Maryland tobacco farmers were willing to invest in one. The old technique -- air-curing -- made more sense for them. After a few years, farmers who had bought the Bibb flue were practically giving them away. Dorsey's apparatus, and flue-cured tobacco, quickly disappeared from the Maryland landscape.

But amazingly, in the late 1980s the furnace from a Bibb flue was found in a Calvert County barn. The MAC Lab's former director, Dr. Julie King, excavated and salvaged it. Her research discovered that a handful of local farmers, mostly neighbors or relatives of George Dorsey, had tried their hands at flue-curing tobacco. But this network of personal relationships to Dorsey wasn't enough to produce a successful business venture. It would seem that the Bibb flue was just a minor footnote in American agricultural history.

Except it wasn't. Although tobacco farmers in the Chesapeake Tidewater region never really adopted flue-curing, their colleagues in North Carolina and the Virginia Piedmont did. And even though the Bibb flue was soon superseded by less expensive and more effective models from other manufacturers, it paved the way for turning this region into "Tobacco Road," the heart of the tobacco industry in the United States until this very day. So when it comes to transformational artifacts, there are few if any in the MAC Lab's collections that are as important as the Bibb furnace.

And in case you were wondering about the title of this Curator’s Choice, Duke University was named after a flue-curing North Carolina tobacco baron!

| References |

|

| King, Julia A. |

| 1997 |

Tobacco, Innovation, and Economic Persistence in Nineteenth-Century Southern Maryland. Agricultural History 71(2):207-236. |

|