Dazzling Duds: Metal Thread in the 17th Century

November 2011

By Sara Rivers Cofield, MAC Lab Curator of Federal Collections

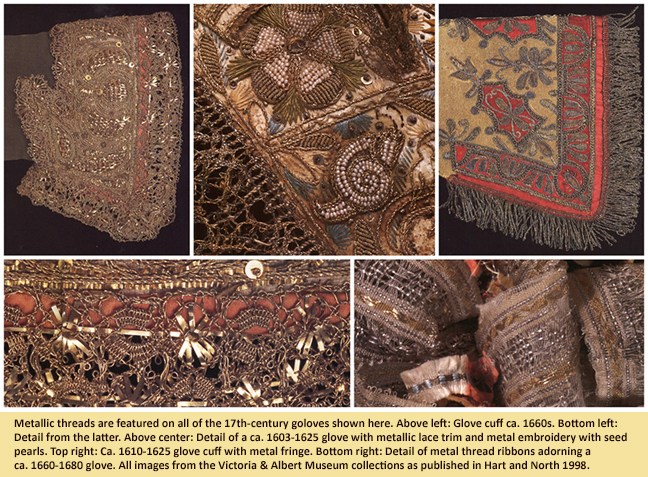

One of the most popular ways for wealthy people of the 17th and 18th centuries to flaunt their status and fashion sense was to dress themselves in clothes and accessories that were made of fine cloth and embellished with metal trims. This finery was not just shiny thread that looked metallic by a trick of the eye, it was actual metal wire wound around silk to make thread, or tiny ribbons of metal that were sewed onto fabric in elaborate patterns.

Pre-made metallic trims, such as fringe, ribbon, and lace, could be purchased for sewing on to clothes at home, but metal embellishments also included embroidery done by needle workers in Europe. These embroiderers were professionals who used skill and specialized tools to sew metallic threads to fabric panels without touching them so that they wouldn't tarnish. Once the embroidery was complete, the garment could be cut and sewn, but care had to be taken with this, too. Metallic bands had sharp edges and wore through threads and fabric more easily than wool or silk embroidery. The effort that these artisans put into the look was worth it though. The embroidery dazzled the eye as threads twinkled in candlelight and impressed onlookers.

Pre-made metallic trims, such as fringe, ribbon, and lace, could be purchased for sewing on to clothes at home, but metal embellishments also included embroidery done by needle workers in Europe. These embroiderers were professionals who used skill and specialized tools to sew metallic threads to fabric panels without touching them so that they wouldn't tarnish. Once the embroidery was complete, the garment could be cut and sewn, but care had to be taken with this, too. Metallic bands had sharp edges and wore through threads and fabric more easily than wool or silk embroidery. The effort that these artisans put into the look was worth it though. The embroidery dazzled the eye as threads twinkled in candlelight and impressed onlookers.

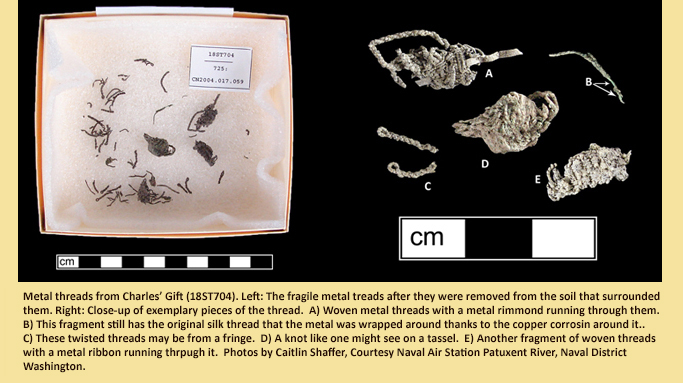

Evidence for the presence of this look in colonial Maryland has been recovered by archaeologists at the Charles' Gift site, which is located on what is now the Naval Air Station Patuxent River in St. Mary’s County. The Charles' Gift site was the home of Nicholas Sewall, his wife Susanna, their eleven children, and their descendants. The Sewalls founded a plantation at the site when Nicholas came of age around 1676. In 1999, archaeologists from R. Christopher Goodwin and Associates recovered some very fragile metal threads from a feature there that dated to the early occupation of the site, circa 1675-1700. Although they are quite fragmentary, the threads include both wire and ribbon forms. Some twisted fragments look like they might have acted as a fringe, and in one case, there is a knot such as might be seen on a tassel.

It is rare for Maryland's archaeologists to get an opportunity to study textiles because organic materials like leather, wool, silk, and linen are subject to rot unless they are deposited in special conditions, like a water-logged well that promotes preservation. In the case of metallic embroidery, however, there is a slightly more durable material involved. The green corrosion on the metal threads found at Charles' Gift indicates that they contain copper, though they may originally have been covered with a thin layer of silver or gold. Copper alloys usually survive well on colonial sites in Maryland, and they have a special skill; their corrosion kills. Copper ions are toxic to the little bugs and microbes that live in soil, feeding on tasty organics like silk. As copper corrodes, it releases poisonous ions that keep the organisms that damage organics away. In this case, the threads encased in copper ribbons are preserved so that archaeologists can study how the threads might have originally looked.

This find is remarkable because there are many factors that prevent metal threads from surviving in the archaeological record. First, metal trim and embroidery was expensive, so only a fraction of Maryland’s population could afford it. Even small amounts of silver or gold in the thread can add up on a garment, and the metal itself had value. Many gentlewomen earned "pin money" in the 18th century by picking precious metal trims off of old garments for recycling. Second, when garments with metallic embroidery were not picked apart and recycled, then it might have been because they represented special garments worthy of being passed down. There are many examples of 17th and 18th-century clothing in museums that exhibit metallic embroidery because such special garments were more likely to be saved, and therefore less likely to end up in the trash pit where archaeologists might find them.

So what does the discovery of metal threads at Charles' Gift say about the status of the Sewall family or their guests? Thankfully, historical records exist to help us put the Sewall family and their showy threads in context. Nicholas Sewall was the stepson of Charles Calvert, the governor of Maryland from 1661-1676. Charles Calvert became the 3rd Lord Baltimore after his father died in 1675. In 1684, Charles Calvert returned to England, leaving trusted Calvert loyalists, such as his stepson Nicholas Sewall, in charge of the colony. It is therefore not surprising to find such threads at the site. The Sewalls were colonial elites, and they most likely hosted other elites like Charles Calvert, creating many opportunities for individuals in fine duds to drop a tassel or two.

The family’s fortunes turned, however, when the Calvert proprietary government was overthrown in 1689, forcing Nicholas Sewall to flee to Virginia. This left his plantation unmanaged and vulnerable to invasion by his enemies. By the time it was safe for him to return years later, the plantation had fallen into ruin and he had to rebuild.

The feature that archaeologists were excavating when they found the metallic threads was a large pit created to get brick clay for the foundation of the Sewall's new 1690s home. This pit was gradually filled with construction debris and household refuse as the new house went up, and when the old house was torn down, that rubble went into the pit, too. Perhaps by then, Sewall’s finest clothes were worn out, damaged by people who had raided the plantation, chewed by mice, or just really out of style. The family was so far removed from the European embroidery industry, that the effort of saving metal threads to sell back to manufacturers may not have been worthwhile. As a result, these metal threads ended up in the refuse pit.

When excavators hit the fragile threads, they carved out the soil that held them and put this soil in a vial. MAC Lab conservator Cait Shaffer later picked the threads out of the dirt and carefully cleaned them, making it possible for a curator like me to look at them under a microscope and get a much better picture of the great finery that the people who walked around Maryland over 300 years ago might have displayed.

| References |

|

| Alcock, N.W. and Nancy Cox |

| 2000 |

Living and Working in Seventeenth Century England: Descriptions and drawings from Randle Holme's Academy of Armory. CD-Rom. London: The British Library Board. |

|

| Hart, Avril and Susan North |

| 1998 |

Historical Fashion in Detail: The 17th and 18th Centuries. London: V&A Publications. |

|

| Hornum, Michael, Andrew Madsen, Christian Davenport, John Clarke, Kathleen Child, and Martha Williams |

| 2001 |

Phase III Archaeological Data Recovery at Site 18ST704, Naval Air Station Patuxent River, St. Mary’s County, Maryland. Report Prepared for Tams Consultants, Inc., Arlington, Virginia. |

|

| Marsh, Gail |

| 2006 |

18th Century Embroidery Techniques. East Sussex, UK: Guild of Master Craftsman Publications Ltd. |

|

| Rivers-Cofield, Sara |

| 2007 |

17th- and Early 18th-Century Architecture along the Patuxent River, Maryland. http://www.jefpat.org/IntroWeb/Introduction.htm. |

|