Anyone for a Game of Ring Taw?

November 2012

By Patricia Samford, MAC Lab Director

Taw, boulder, bumboozer, commies, masher, popper, marrididdles, shooter, bumbo, crock, bowler, tonk, godfather, tom bowler and biggie. All of these words—some commonplace, everyday nouns and the others quite curious terms—are part of a lexicon that has largely disappeared from our language. They are names once used to describe marbles.

Taw, boulder, bumboozer, commies, masher, popper, marrididdles, shooter, bumbo, crock, bowler, tonk, godfather, tom bowler and biggie. All of these words—some commonplace, everyday nouns and the others quite curious terms—are part of a lexicon that has largely disappeared from our language. They are names once used to describe marbles.

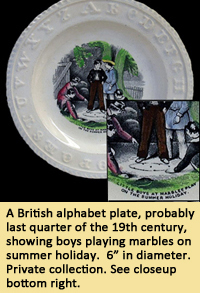

In this age of fast-paced digital entertainment, games with marbles must seem archaic to today’s plugged-in youth. This was not always the case, though. Marbles are one of the most common children’s toys found on colonial and post-colonial archaeological sites in North America. Paintings and prints of children—usually boys kneeling in a circle in the dirt playing ringers or standing in a group trading their finest specimens—abound in western art, starting as early as Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s painting Children's Games (1560). Marbles were used in a variety of games; the only game that seemed to have been played primarily by girls was five stones, a game similar to jacks that involved a marble and four sheep talus (ankle) bones (Gartley and Carskadden 1998:23).

In this age of fast-paced digital entertainment, games with marbles must seem archaic to today’s plugged-in youth. This was not always the case, though. Marbles are one of the most common children’s toys found on colonial and post-colonial archaeological sites in North America. Paintings and prints of children—usually boys kneeling in a circle in the dirt playing ringers or standing in a group trading their finest specimens—abound in western art, starting as early as Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s painting Children's Games (1560). Marbles were used in a variety of games; the only game that seemed to have been played primarily by girls was five stones, a game similar to jacks that involved a marble and four sheep talus (ankle) bones (Gartley and Carskadden 1998:23).

Over the years, marbles were made from a number of materials, including stone, unglazed earthenware, glazed stoneware, porcelain, and glass (Block 1999; Gartley and Carskadden 1998; Randall and Webb 1988). Many marbles were made and imported from Germany, but North American production really took off in the early twentieth century (Carskadden and Gartley 1990:55).

Over the years, marbles were made from a number of materials, including stone, unglazed earthenware, glazed stoneware, porcelain, and glass (Block 1999; Gartley and Carskadden 1998; Randall and Webb 1988). Many marbles were made and imported from Germany, but North American production really took off in the early twentieth century (Carskadden and Gartley 1990:55).

A nice collection of stoneware marbles was found among the collapsed timbers filling a late 19th-century cellar at the Federal Reserve Site (18BC27) in Baltimore. These white bodied  stoneware marbles, finished with a colorful glaze, are what collectors call "Benningtons" or "Bennies". Benningtons were produced during last three decades of nineteenth century and first decade of twentieth century (Gartley and Carskadden 1998:135). Typical of Benningtons, the Federal Reserve marbles have circular bare spots in the glaze, caused by the marbles resting against one another in the kiln. Some of them display pock marks on their glazed surfaces; damage typical of heavy use. They range in diameter from .5" to 1.5", with the larger marbles probably serving as shooters.

stoneware marbles, finished with a colorful glaze, are what collectors call "Benningtons" or "Bennies". Benningtons were produced during last three decades of nineteenth century and first decade of twentieth century (Gartley and Carskadden 1998:135). Typical of Benningtons, the Federal Reserve marbles have circular bare spots in the glaze, caused by the marbles resting against one another in the kiln. Some of them display pock marks on their glazed surfaces; damage typical of heavy use. They range in diameter from .5" to 1.5", with the larger marbles probably serving as shooters.

While marbles are a relatively common find on nineteenth-century archaeological sites, what makes these marbles a bit unusual is that all seven of them were all found together. It is easy to imagine them nestled in a leather or cloth bag, awaiting their next game.

| References |

|

| Block, Robert |

| 1999 |

Marbles Illustrated; Prices at Auction. Schiffer Publishing, Atglen, Pennsylvania. |

|

| Carskadden, Jeff and Richard Gartley |

| 1990 |

A Preliminary Seriation of 19th-Century Decorated Porcelain Marbles. Historical Archaeology 24(2):55-69. |

|

| Gartley, Richard and Jeff Carskadden |

| 1998 |

Colonial Period and Early 19th-Century Children's Toy Marbles; Historiy and Identification for the Archaeologist and Collector. The Muskingum Valley Archaeological Survey, Zanesville, Ohio. |

|

| Randall, Mark E. and Dennis Webb |

| 1988 |

Greenberg's Guide to Marbles. Greenberg Publishing Company, Sykesville, Maryland. |

|