Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory

Main_Content

Curator's Choice 2013

Who Bit the Bullet?: Let Slip the Pigs of War!

February 2013

By Edward Chaney, MAC Lab Deputy Director

| In the colonial era, soldiers sometimes accused their enemies of chewing musket balls and then dipping them in poison or feces in order to cause infection and make gunshot wounds more deadly. The tooth indentations would supposedly help secure the "poison" to the shot (Bell 2012). |

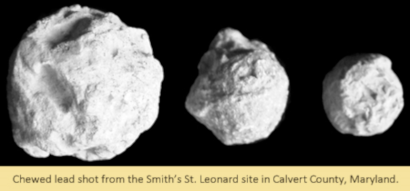

Archaeologists often recover musket balls with tooth marks on them. Human teeth were long assumed to be the main cause of these marks, through various means. Most obvious was “biting the bullet” to cope with pain, especially from battlefield wounds. The marks could also be produced by soldiers sucking on lead shot to generate saliva, hoping to alleviate thirst. And it has been suggested that soldiers might chew scraps of lead into a ball shape if no shot mold was available, or bite into them to create segments that would separate on impact and cause a larger wound, much like a modern dum-dum bullet (Brown 1980:328; Muzzle Loading Forum n.d.; Sivilich 2009).

Archaeologists often recover musket balls with tooth marks on them. Human teeth were long assumed to be the main cause of these marks, through various means. Most obvious was “biting the bullet” to cope with pain, especially from battlefield wounds. The marks could also be produced by soldiers sucking on lead shot to generate saliva, hoping to alleviate thirst. And it has been suggested that soldiers might chew scraps of lead into a ball shape if no shot mold was available, or bite into them to create segments that would separate on impact and cause a larger wound, much like a modern dum-dum bullet (Brown 1980:328; Muzzle Loading Forum n.d.; Sivilich 2009).

In recent years another source of the marks has been suggested: chewing by pigs and rodents. Rodents tend to leave distinct fine striations on lead shot, but the chewing and digestion of a musket ball by a pig – which would happen as the animal is rooting around the ground looking for food – can leave it covered with tooth marks. Animal tooth impressions might be more likely on a residential site, but they have also been found at battlefields (Sivilich 2009).

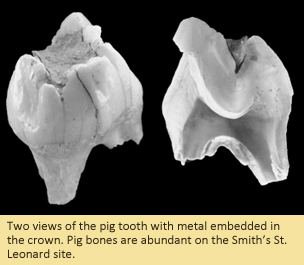

| Tooth fillings made with liquid lead or other soft metals were sometimes used during the colonial period. However, a dentist examined the Smith's St. Leonard tooth and confirmed that it was non-human, as evidenced by the cusp height and very thick enamel layer, and showed no sign of decay that would require a filling. |

A recent discovery supports the idea of pigs as a source of tooth marks on lead shot. A pig tooth, split in half, was found at the Smith’s St. Leonard site, an early 18th-century plantation at Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum. Embedded deeply into the crown of the tooth is a foreign object. Based on x-rays and visual examination, it is white metal, probably lead. The metal has been forced into the crevices of the crown, and its top has been pressed smooth and even with the surface of the tooth, probably from the pressure of repeated chewing. While we do not know if the source of the metal is a musket ball or some other object, the Smith’s St. Leonard tooth does show that pigs would chew on metallic things, and bite down on them hard enough to jam the material in their teeth, so they could be a source for some of the marks found on musket balls.

A recent discovery supports the idea of pigs as a source of tooth marks on lead shot. A pig tooth, split in half, was found at the Smith’s St. Leonard site, an early 18th-century plantation at Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum. Embedded deeply into the crown of the tooth is a foreign object. Based on x-rays and visual examination, it is white metal, probably lead. The metal has been forced into the crevices of the crown, and its top has been pressed smooth and even with the surface of the tooth, probably from the pressure of repeated chewing. While we do not know if the source of the metal is a musket ball or some other object, the Smith’s St. Leonard tooth does show that pigs would chew on metallic things, and bite down on them hard enough to jam the material in their teeth, so they could be a source for some of the marks found on musket balls.

Future research may shed more light on the tooth, but for now, th-th-that’s all, folks!

| References |

|

| Bell, J. L. |

| 2012 |

"Both poisoned and chewed the musket balls." http://boston1775.blogspot.com, entry for June 18, 2012. Accessed August 24, 2012. |

|

| Brown, M. L. |

| 1980 |

Firearms in Colonial America: The Impact on History and Technology, 1492-1792. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. |

|

| Muzzle Loading Forum |

| n.d. |

http://www.muzzleloadingforum.com. Accessed August 24, 2012 |

|

| Sivilich, Daniel M. |

| 2009 |

What the Musket Ball Can Tell: Monmouth Battlefield State Park, New Jersey. In Fields of Conflict: Battlefield Archaeology from the Roman Empire to the Korean War. Edited by Douglas Scott, Lawrence Babits, and Charles Haecker. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, Inc. |

|