Peas, Beans, Corn and Wheat

April 2013

By Alex Glass, MAC Lab Public Archaeology Asst.

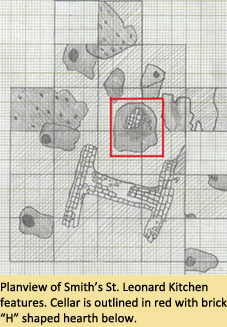

Archaeological excavations in the kitchen area at the 18th century Smith’s St. Leonard site, located at JPPM, recovered a high volume of food related artifacts. In particular, the brick-capped cellar in front of one of the kitchen hearths provided many charred seed remains for analysis. Studying botanical remains can add further information about diet, agricultural practices, trade and environment (Miller 1989:50). Some of the seed and nut remains identified in the cellar fill include corn, black walnut, wheat, grape, peas, and beans. Most of these were probably unintentionally burnt, but could have been dropped during food preparation and later deposited into the nearby hearth.

Archaeological excavations in the kitchen area at the 18th century Smith’s St. Leonard site, located at JPPM, recovered a high volume of food related artifacts. In particular, the brick-capped cellar in front of one of the kitchen hearths provided many charred seed remains for analysis. Studying botanical remains can add further information about diet, agricultural practices, trade and environment (Miller 1989:50). Some of the seed and nut remains identified in the cellar fill include corn, black walnut, wheat, grape, peas, and beans. Most of these were probably unintentionally burnt, but could have been dropped during food preparation and later deposited into the nearby hearth.

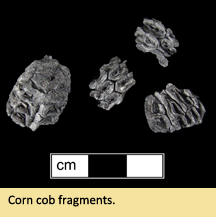

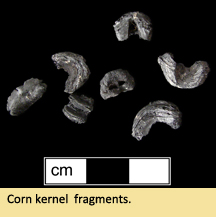

During the early ownership of the site, several land disputes occurred; two of which describe locations where fields, gardens, barns and even grape vines existed (MDhR 50,082-16-11, MD; King and Winnik 1994). A 1773 deposition given by Roger Johnson ftn1, a former servant or slave of landowner Walter Smith, indicates that near a fence was “ground to be tended in corn” (King and Winnik 1994: Appendix II). On a survey plat drawn for the same case a “cornhouse” is marked as standing near the Smith’s main dwelling (MdHR 50,082-92. A cornhouse was used as “a storage building for shelled corn or for ears of corn”, and 30 barrels of corn are listed in Walter Smith’s 1748 probate inventory (Lounsbury 1994: 94; MSA, Inventories, 45-37). The kernels and cobs found in the kitchen cellar could be remains of corn grown in the field near the fence, and stored in the cornhouse.

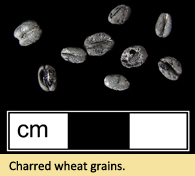

A wheat house was also identified on the 1773 plat, and would have been used similarly to the cornhouse. Once wheat has matured in the field it must be cut, bundled and then taken to a sheltered place, dried and threshed (Perry 1977: 17). Fifty-four bushels of wheat are listed in Walter Smith’s. probate inventory, possibly waiting to be ground at his nearby mill for use as bread flour ftn2. The complete grains found in the kitchen cellar could have been stored or processed there.

A wheat house was also identified on the 1773 plat, and would have been used similarly to the cornhouse. Once wheat has matured in the field it must be cut, bundled and then taken to a sheltered place, dried and threshed (Perry 1977: 17). Fifty-four bushels of wheat are listed in Walter Smith’s. probate inventory, possibly waiting to be ground at his nearby mill for use as bread flour ftn2. The complete grains found in the kitchen cellar could have been stored or processed there.

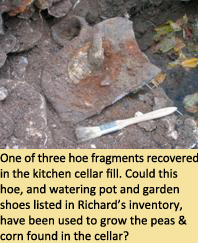

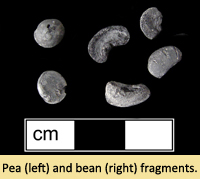

A few bean and pea fragments were also found in the kitchen cellar. These were often dried for later use rather than eaten fresh, and at his death in 1714 Richard Smith had 20 bushels of "Indian peas" ftn3 (Leach 1985; MSA, Inventories & Accounts, 36c-1). The 1773 plat and depositions have no suggestion of where these legumes were cultivated, but they could have been grown in Walter Smith’s slaves’ "truck patch" ftn4, mentioned in a 1768 court deposition by Benjamin Mackall (MDhR 50,082-16-11).

A few bean and pea fragments were also found in the kitchen cellar. These were often dried for later use rather than eaten fresh, and at his death in 1714 Richard Smith had 20 bushels of "Indian peas" ftn3 (Leach 1985; MSA, Inventories & Accounts, 36c-1). The 1773 plat and depositions have no suggestion of where these legumes were cultivated, but they could have been grown in Walter Smith’s slaves’ "truck patch" ftn4, mentioned in a 1768 court deposition by Benjamin Mackall (MDhR 50,082-16-11).

Food in the 18th century colonies was limited to season, storage, cultivation, and what imported goods could be afforded. Consequently, most rural families depended on the foodstuffs they produced on the land themselves. The seed and nut remains found in the Smith family’s kitchen cellar, together with the site’s historical documents demonstrate the relationship between the Smith’s land and their food.

| Footnotes |

|

| 1 |

Possibly the "mulatto man named Roger with 3 ½ years left to serve" listed on Walter Smith’s 1748 inventory. |

|

| 2 |

In 1714 Walter Smith is bequeathed land "called Blinkhorn together with the mill that is therin" (MSA,Wills,14-83). |

|

| 3 |

Possibly cowpeas or black eyed peas. These were a staple in slave gardens and diet, but mostly used as field beans by plantation owners (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation 2013) |

|

| 4 |

"a small area devoted to the production of vegetables usually for domestic use" (Merriam-Webster 2013) |

|