Murder in Maryland: "Devills" Masquerading

as Colonial Gentlemen

October 2013

By Erin Wingfield, MAC Lab Collections Assistant

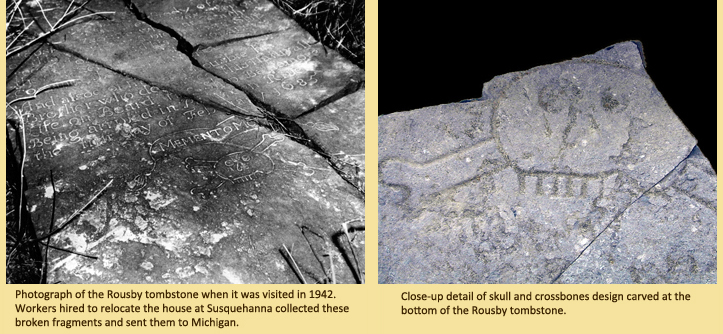

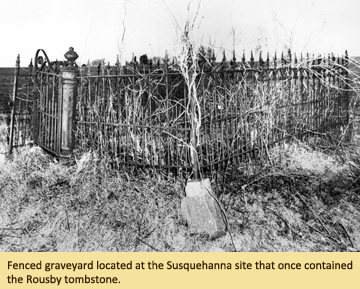

An unusually large tombstone was once located on what is now the Naval Air Station Patuxent River in St. Mary’s County, MD. This 1,000-pound limestone slab once marked the grave of Christopher Rousby and his brother John (Desmon 2005). The epitaph lists not only their names and dates but also describes the stabbing that led to Christopher Rousby’s death. The story of Rousby’s murder was once notorious in St. Mary’s County. However, by the 1940s, when the Navy altered the landscape and the tombstone was moved, this tale had faded into obscurity.

Christopher Rousby was appointed King's Tax Collector in 1676 (King 2012:33). His position and abrasive personality often brought him into conflict with the Governor of Maryland, Lord Baltimore. Baltimore called Rousby "Evill" and a "Devill", accused him of harassing merchants, padding his pockets, demanding gifts, and speaking treason (Browne 1887:274-276; Galke 2000:21; King 2012:33). In turn, Rousby accused Baltimore of cheating the King, hindering tax collection, trying to paint his character "as black as hell", and "throwing dirt to see what sticks" (Browne 1887:290, 303). Baltimore even requested Rousby be replaced by more evenhanded collectors, his own sons-in-law (Browne 1887:286). However, his request was denied. Instead, Baltimore was charged 2,500 pounds for interfering with the tax collector's duties (Galke 2000:22; Browne 1887:305). Even after Baltimore returned to England, the ill will between the King's men and the colonists continued. Lord Baltimore's cousin, Colonel George Talbot, continued to keep an eye on affairs in his absence. While staying in St. Mary's City, Talbot grew angry listening to merchants' and shippers' complaints and decided to confront Rousby with these accusations (Pogue 1968:324).

On October 31, 1684, All Hallows Eve, these disputes took a darker turn. That night, Rousby was having dinner with Captain Thomas Allen of the Royal Navy aboard his ship, the Quaker. Allen had gained a similar reputation for harassing and mocking the people of Maryland. Talbot rowed to meet them and after declining their invitation to dinner, began to argue over the King's authority in Maryland. There are varying accounts of this confrontation. Some portray Talbot as a drunken hothead yelling accusations at Rousby. Others describe Talbot making unwelcome passes at Allen before losing his temper, pulling out a dagger, and stabbing Rousby in the chest. Rousby died soon after (Galke 2000:22; King 2012:34).

On October 31, 1684, All Hallows Eve, these disputes took a darker turn. That night, Rousby was having dinner with Captain Thomas Allen of the Royal Navy aboard his ship, the Quaker. Allen had gained a similar reputation for harassing and mocking the people of Maryland. Talbot rowed to meet them and after declining their invitation to dinner, began to argue over the King's authority in Maryland. There are varying accounts of this confrontation. Some portray Talbot as a drunken hothead yelling accusations at Rousby. Others describe Talbot making unwelcome passes at Allen before losing his temper, pulling out a dagger, and stabbing Rousby in the chest. Rousby died soon after (Galke 2000:22; King 2012:34).

Allen had Talbot arrested and placed in irons. Fearing Talbot would escape justice if brought to Maryland, Allen instead took him to Virginia. However, while both governments were arguing over jurisdiction, Talbot, assisted by his jailers, wife and friends, escaped from prison. The jailors were subsequently arrested but escaped the following day (Browne 1887:453). Accounts of Talbot's flight describe him wearing disguises and eating food brought by trained falcons. Informants also stated Talbot was hiding at home in Maryland, protected by friends and neighbors (King 2012:34-35). Eventually, he was caught and brought to trial in Virginia where the jury convicted him of murder, describing Talbot as being, "moved and seduced by the Instigation of the Divel" (Browne 1887:479). Talbot was sentenced to death but later pardoned by the King after paying 1,000 pounds and offering an apology (Browne 1898:480; Pogue 1968:325).

When the Navy began constructing the Naval Air Station Patuxent River in the 1940s, the house that stood nearby the Rousby tombstone was offered to the Henry Ford Museum for their Greenfield Village exhibit. Believing the house to be Rousby’s, the Museum accepted and the building was moved to Dearborn, Michigan (King 2012:21-22, 88). The workmen also collected the broken pieces of Rousby’s tombstone and "a bag of bones" found underneath it. Many years later, researchers determined the house was not actually Rousby’s and instead was constructed about 150 years after his death. The Henry Ford Museum changed their interpretation of the house and placed the tombstone in storage. The bones were also examined and determined to be from three separate individuals; none Caucasian male. Since none of these individuals could have been Christopher Rousby or his brother, John, the remains were cremated and reinterred. The location of the remains of both Rousbys is still a mystery (Desmon 2005).

When the Navy began constructing the Naval Air Station Patuxent River in the 1940s, the house that stood nearby the Rousby tombstone was offered to the Henry Ford Museum for their Greenfield Village exhibit. Believing the house to be Rousby’s, the Museum accepted and the building was moved to Dearborn, Michigan (King 2012:21-22, 88). The workmen also collected the broken pieces of Rousby’s tombstone and "a bag of bones" found underneath it. Many years later, researchers determined the house was not actually Rousby’s and instead was constructed about 150 years after his death. The Henry Ford Museum changed their interpretation of the house and placed the tombstone in storage. The bones were also examined and determined to be from three separate individuals; none Caucasian male. Since none of these individuals could have been Christopher Rousby or his brother, John, the remains were cremated and reinterred. The location of the remains of both Rousbys is still a mystery (Desmon 2005).

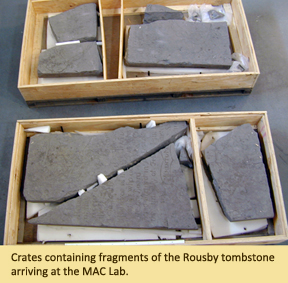

The Rousby tombstone sat in storage for almost 20 years before a local individual in Southern Maryland made inquiries and requested its return. The MAC Lab was contacted and worked with the Henry Ford Museum to have it shipped back to Maryland. In 2002, two large crates arrived at the lab containing fragments of the tombstone. The hope is that one day the tombstone can be displayed to remind visitors of this wicked, but noteworthy, event in Maryland's history (Desmon 2005).

| References |

|

| Browne, William Hand, Ed. |

| 1887 |

Archives of Maryland Volume V: Proceedings of the Council of Maryland 1667-1687. Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, MD. |

| 1898 |

Archives of Maryland Volume XVII: Proceedings of the Council of Maryland 1681-1685. Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, MD. |

|

| Desmon, Stephanie |

| 2005 |

"Lost Soul." Baltimore Sun. June 21, 2005. |

|

| Galke, Laura J. and Michael W. Kell |

| 2000 |

Phase I Archaeological Resources Inventory of the Harper’s Creek Area Naval Air Station Patuxent River, St. Mary’s Country, Maryland. |

|

| King, Julia A. |

| 2012 |

Archaeology, Narrative, and the Politics of the Past. University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, TN. |

|

| Pogue, Robert E. T. |

| 1968 |

Yesterday in Old St. Mary’s County. Robert E. T. Pogue, Bushwood, MD. |

|