The Line of Sight: A Brief History of Eyeglasses

December 2013

By Christy Nisbet, MAC Lab Intern

The names Spec, Four-eyes and Poindexter all conjure up the image of a person wearing thick glasses with tape wrapped around the bridge. While these names may bring up childhood fears for people who wore glasses, at one time having glasses was a symbol of wealth.

The names Spec, Four-eyes and Poindexter all conjure up the image of a person wearing thick glasses with tape wrapped around the bridge. While these names may bring up childhood fears for people who wore glasses, at one time having glasses was a symbol of wealth.

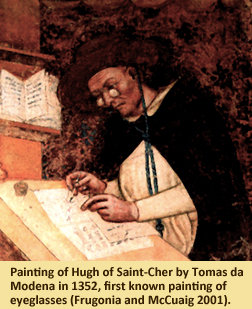

The earliest form of today's eyeglasses was seen in first century AD, when a tutor for Nero used a "globe or glass filled with water" to enlarge and read letters more clearly (Kriss and Kriss 1998). A form of glasses then appeared in Alhazen’s Book of Optics, which, when translated into Latin, brought Alhazen's findings to Europe and helped bring about the invention of glasses there in the 13th century (Kriss and Kriss 1998).

The earliest form of today's eyeglasses was seen in first century AD, when a tutor for Nero used a "globe or glass filled with water" to enlarge and read letters more clearly (Kriss and Kriss 1998). A form of glasses then appeared in Alhazen’s Book of Optics, which, when translated into Latin, brought Alhazen's findings to Europe and helped bring about the invention of glasses there in the 13th century (Kriss and Kriss 1998).

In 1907, a German professor claimed that eyeglasses were invented much earlier in India (Agarwal 1971). According, however, to a sermon given by Friar Giordano da Pisa in 1306, the first eyeglasses were created in 1286 in Italy (Ilardi 2007). These eyeglasses were able to correct farsightedness and presbyopia. Later advancement to eyeglasses would come with Benjamin Franklin’s invention of the bifocal (College of Optometrists 2013). Previously, glasses had been worn in many ways, such as tying the frames with ribbon around the face, by holding up the glasses by hand or a handle (also called a lorgnette) or by the bridge of the glasses pinching the nose (called a pince-nez).

The exact year of the creation of the "modern" way of wearing glasses, with the temple arms over the ears, is unknown; however, it has been suggested that it started in the 18th century. Today, eyeglasses are worn for protection from the sun and workplace hazards, for corrective vision and even for style.

The exact year of the creation of the "modern" way of wearing glasses, with the temple arms over the ears, is unknown; however, it has been suggested that it started in the 18th century. Today, eyeglasses are worn for protection from the sun and workplace hazards, for corrective vision and even for style.

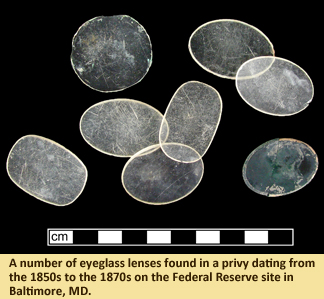

A number of eyeglass lenses were found in a privy dating from the 1850s to the 1870s on the Federal Reserve site in Baltimore (McCarthy and Basalik 1980). During the excavation of the privy, archaeologists found only the lens of the glasses. The absence of the surrounding frames could be due to the fact that only 50 percent of the privy was dug or, more likely, because the frames were made from a cheap metal like copper or iron that had disintegrated by the time the excavation had begun.

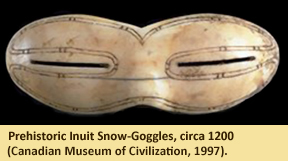

In this feature there was also a lens from a pair of sunglasses. The earliest  known sunglasses were made from animal bone by the Inuit people to protect themselves from the bright northern sun (Acton et al. 2006). Sunglasses were also found in China as early as the 12th century. The glasses from the Federal Reserve privy were most likely a form of James Ayscough’s tinted lenses. Ayscough started working with tinted lenses in the middle of the 18th century; however, these green or blue lenses were used for vision impairments and not for protection against the sun. The "modern" idea of sunglasses didn’t come about until the early 20th century.

known sunglasses were made from animal bone by the Inuit people to protect themselves from the bright northern sun (Acton et al. 2006). Sunglasses were also found in China as early as the 12th century. The glasses from the Federal Reserve privy were most likely a form of James Ayscough’s tinted lenses. Ayscough started working with tinted lenses in the middle of the 18th century; however, these green or blue lenses were used for vision impairments and not for protection against the sun. The "modern" idea of sunglasses didn’t come about until the early 20th century.

| References |

|

| Acton, Johnny, Tania Adams and Matt Packer |

| 2006 |

Origin of Everyday Things. Sterling, New York. |

|

| Agarwal, R. K. |

| 1971 |

Origin of Spectacles in India. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 55(2): 128-29. |

|

| Canadian Museum of Civilization |

| 1997 |

Prehistoric Inuit Snow-Goggles, circa 1200. Canadian Museum of Civilization. |

|

| College of Optometrists |

| 2013 |

The Inventor of Bifocals? The College of Optometrists. Website. http://www.college-optometrists.org accessed 2 Aug. 2013. |

|

| Frugonia, Chiara and William McCuaig |

| 2001 |

Books, Banks, Buttons and Other Inventions from the Middle Ages. Columbia University Press, New York. |

|

| Greco, El |

| 1600 |

Portrait of a Cardinal. 1600. Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

|

| Ilardi, Vincent |

| 2007 |

Renaissance Vision from Spectacles to Telescopes |

|

| Kriss, Timothy C. and Vesna Martich Kriss |

| 1998 |

History of the Operating Microscope: From Magnifying Glass to Microneurosurgery. Neurosurgery 42(4): 899–907. |

|

| McCarthy, John P. and Kenneth J. Basalik |

| 1980 |

1980 Summary Report of Archaeological Investigations; Federal Reserve Bank Site. Mid-Atlantic Archaeological Research, Inc., Newark. |

|