A Human’s Best (and Oldest) Friend

January 2014

By Rebecca Morehouse, MAC Lab State Curator

“The earth trembled and a great rift appeared, separating the first man and woman from the rest of the animal kingdom. As the chasm grew deeper and wider, all other creatures, afraid for their lives, returned to the forest – except for the dog, whom after much consideration, leapt the perilous rift to stay with the humans on the other side. His love for humanity was greater than his bond for other creatures, he explained, and he willingly forfeited his place in paradise to prove it.” - Native American folk tale (DeMello 2012: 84).

“The earth trembled and a great rift appeared, separating the first man and woman from the rest of the animal kingdom. As the chasm grew deeper and wider, all other creatures, afraid for their lives, returned to the forest – except for the dog, whom after much consideration, leapt the perilous rift to stay with the humans on the other side. His love for humanity was greater than his bond for other creatures, he explained, and he willingly forfeited his place in paradise to prove it.” - Native American folk tale (DeMello 2012: 84).

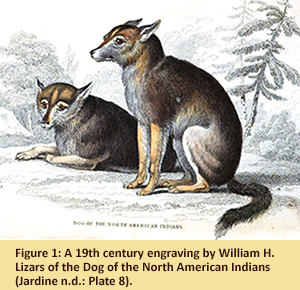

Domestic dogs and their wolf ancestors have played an integral role in human history. Archaeological, historical and genetic research has provided insights into the domestication of dogs, their likely migration with humans across the Bering Straits from Asia, and the deep bond that formed between Native Americans and their canine companions (Koeppel N.D.). Archaeological evidence of the relationship between humans and dogs indicates that canine domestication may have taken place as far back as 15,000 years ago, maybe earlier (Morey 1994: 339). This would suggest that dogs became part of the lives of humans while they were still living a semi-sedentary existence as hunters and gatherers and prior to transitioning to more permanent settlements.

Humans and wolves would have come in contact with one another while hunting the same game, placing wolves in an excellent position to scavenge anything humans left behind (Morey 1994: 339). This early hunting/scavenging relationship evolved into one of cohabitation and, according to archaeozoologist Susan Crockford, probably resulted in wolves domesticating themselves rather than being deliberately tamed by humans (Lobell and Powell 2010).

Humans and wolves would have come in contact with one another while hunting the same game, placing wolves in an excellent position to scavenge anything humans left behind (Morey 1994: 339). This early hunting/scavenging relationship evolved into one of cohabitation and, according to archaeozoologist Susan Crockford, probably resulted in wolves domesticating themselves rather than being deliberately tamed by humans (Lobell and Powell 2010).

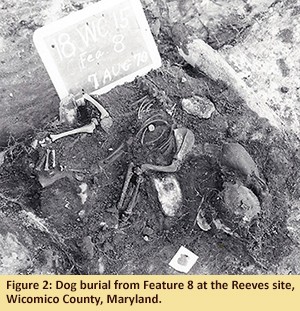

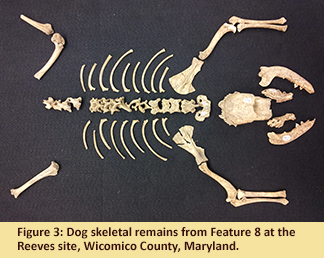

In Maryland, a small number of Native American sites have yielded evidence of this human-dog relationship. At the Reeves site on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, two dog burials were excavated, dating to the Late Woodland period (A.D. 950 to 1600). Both burials were from relatively young dogs whose skeletal epiphyses and cranial plates had not yet completely fused (Figures 2 and 3).

Almost the entire articulated skeleton of each animal was present and the bones were positioned in such a way as to suggest intentional burial after death. The bones show no sign of cutting or butchering so it is unlikely that these animals were used as a food source. Perhaps they died of disease or some other trauma not immediately apparent on the skeletal remains.

Almost the entire articulated skeleton of each animal was present and the bones were positioned in such a way as to suggest intentional burial after death. The bones show no sign of cutting or butchering so it is unlikely that these animals were used as a food source. Perhaps they died of disease or some other trauma not immediately apparent on the skeletal remains.

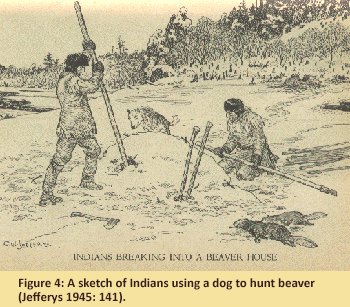

Archaeological evidence from prehistoric sites throughout the world suggests that domesticated dogs were treated not just as companions, but were used for hunting (Figure 4), protection, clothing, ceremonial food or sacrifices, as well as guides in the afterlife (Kerber 1997: 81).

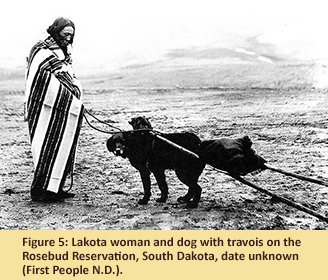

The Jesuits, some of the first Europeans to arrive in northeastern America, observed Native Americans using dogs as hunting companions for game, as well as for their enemies (Kerber 1997: 88). Pathologies found on some dog skeletons recovered from archaeological contexts, as well as ethnographic evidence, indicates that dogs were also being used as beasts of burden (First People) (Figure 5). Native Americans also wore the skins of dogs and wolves. In 1535, Jacques Cartier described seeing Huron men wearing capes and masks of “dogges skinnes white and blacke” (Cartier 1906: 52).

The Jesuits, some of the first Europeans to arrive in northeastern America, observed Native Americans using dogs as hunting companions for game, as well as for their enemies (Kerber 1997: 88). Pathologies found on some dog skeletons recovered from archaeological contexts, as well as ethnographic evidence, indicates that dogs were also being used as beasts of burden (First People) (Figure 5). Native Americans also wore the skins of dogs and wolves. In 1535, Jacques Cartier described seeing Huron men wearing capes and masks of “dogges skinnes white and blacke” (Cartier 1906: 52).

The broken or butchered bones of dogs have been found on archaeological sites alongside the bones of other animals commonly used for food such as deer and bear (Wyman 1868: 575-576; Kerber 1997: 82). An early 17th century written account by Henry Hudson described how the Mahicans “killed at once a fat dog, and skinned it in great haste” in honor of Hudson’s visit (Laet 1909: 49).

Hudson’s description indicates that the eating of dogs was usually associated with some kind of ritual or ceremony (Kerber 1997: 89). In 1612, Father Pierre Baird wrote about the ritual slaughter of dogs during a Micmac banquet called a dog feast in honor of a dying man (Thwaites N.D. Volume II). These sacrificed dogs were either cooked and eaten or simply buried with the individual to act as a guide to “go before him into the other world” (Thwaites Volume III).

Hudson’s description indicates that the eating of dogs was usually associated with some kind of ritual or ceremony (Kerber 1997: 89). In 1612, Father Pierre Baird wrote about the ritual slaughter of dogs during a Micmac banquet called a dog feast in honor of a dying man (Thwaites N.D. Volume II). These sacrificed dogs were either cooked and eaten or simply buried with the individual to act as a guide to “go before him into the other world” (Thwaites Volume III).

Today, while dogs are still used as hunting aides, guardians and protectors, the vast majority in the United States simply serve as our companions. The deep connection we share with our dogs makes it impossible to conceive of them as a sacrificial animal or a source of food. Dogs share our lives and homes as members of our families and when they die, we mourn their passing, usually affording them a ritual burial in a marked grave. This emotional bond is the legacy of those first wolves which chose to follow human hunters in search of food over 15,000 years ago.

Other Maryland sites with dog burials include: the Winslow site in Montgomery County, the Lankford sire in Dorchester County, and Pig Point in Anne Arundel County.

| References |

|

| Cartier, Jacques |

| 1906 |

"A Shorte and Briefe Narration 1535-1536". In Early English and French Voyages, 1534-1608, edited by H.S. Burrage, pp. 37-88. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. Web resource. https://archive.org/stream/earlyenglishandf001725mbp#page/n5/mode/1up accessed December 13, 2013. |

|

| DeMello, Margo |

| 2012 |

Animals and Society: An Introduction to Human-Animal Studies. New York: Columbia University Press. Web resource. http://books.google.com/books?id=Nl7ZBL2O3XAC&printsec=frontcover&dq=animals+and+society+demello+ebook&hl=en&

sa=X&ei=VzmvUtTpHKfJsQSIzIBg&ved=0CEgQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=animals%20and%20society%20demello%20ebook&f=false accessed December 13, 2013. |

|

| First People |

| n.d. |

Web resource. http://www.firstpeople.us/pictures/art/odd-sizes/ls/Lakota-Woman-And-Dog-Travois-Rosebud-Reservation-800x571.html accessed December 13, 2013. |

|

| Jardine, William, ed. |

| n.d. |

The Naturalist’s Library. Mammalia. Dogs, Volume II. London: Chatto and Windus, Piccadilly. Web resource. https://archive.org/stream/naturalistslibra19jardrich#page/176/mode/thumb accessed December 13, 2013. |

|

| Jeffreys, C.W. |

| 1945 |

The Picture Gallery of Canadian History, Volume 2, 1763-1830. Toronto: The Ryerson Press. Web resource. http://www.cwjefferys.ca/picture-gallery-of-canadian-history-vol-2#.Uq86aPRDuVM accessed December 13, 2013. |

|

| Kerber, Jordan E. |

| 1997 |

"Native American Treatment of Dogs in Northeastern North America: Archaeological and Ethnohistorical Perspectives" in Archaeology of Eastern North America 25: 81-96. |

|

| Koeppel, Christopher |

| n.d. |

Prehistoric Indian Dogs. Web resource. http://www.in.gov/dnr/historic/files/american_dogs.pdf accessed December 13, 2013. |

|

| Laet, Joannes de |

| 1909 |

"From the 'New World', 1625, 1630, 1633, 1640". In Narratives of New Netherland, 1609-1664, edited by J.F. Jameson, pp. 29-60. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. Web resource. https://archive.org/stream/narrativesofnewn01jame#page/49/mode/1up accessed December 13, 2013. |

|

| Lobell, Jarrett A. and Eric Powell |

| 2010 |

"More than Man's Best Friend" in Archaeology (63)5, September/October. Web resource. http://archive.archaeology.org/1009/dogs/ accessed December 13, 2013. |

|

| Morey, Darcy F. |

| 1994 |

"The Evolution of the Domestic Dog" in American Scientist 82 (4): 336-347. |

|

| Thwaites, Reuben Gold, ed. |

| n.d. |

The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France, 1610-1791, Volume II, Acadia, 1612-1614. Web resource. http://puffin.creighton.edu/jesuit/relations/relations_03.html accessed December 13, 2013. |

|

| Thwaites, Reuben Gold, ed. |

| _n.d. |

The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France, 1610-1791, Volume III, Acadia, 1611-1616. Web resource. http://puffin.creighton.edu/jesuit/relations/relations_03.html accessed December 13, 2013. |

|

| Wyman, Jeffries |

| 1868 |

"An Account of Some Kjokkenmoeddings, or Shell Heaps, in Maine and Massachussetts" in American Naturalist 1(11): 561-584. |

|