The Rise of Balloon Flight

February 2014

By Caitlin Shaffer, MAC Lab Conservator

Nothing will ever quite equal that moment of total hilarity that filled my whole body at the moment of take-off… It was not mere delight. It was a sort of physical rapture… I’m finished with Earth. From now on our place is in the sky! -Dr Jacques Charles, 1783 (Holmes 2013:17)

Nothing will ever quite equal that moment of total hilarity that filled my whole body at the moment of take-off… It was not mere delight. It was a sort of physical rapture… I’m finished with Earth. From now on our place is in the sky! -Dr Jacques Charles, 1783 (Holmes 2013:17)

For as long as people have looked towards the sky, we have dreamed of flight. While the earliest flying apparatuses – capes, wings, kites – were less than successful, the late 18th century saw the first use of hot air and hydrogen-filled balloons, inventions that opened up the skies and captured the world’s imagination.

The first successful balloon launchings took place in Paris in 1783 by Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier. Although they did not fully understand how hot air worked to lift the balloons, they were able to demonstrate that they could float at great heights, travel through the air, and were safe for passengers - the first of which were a sheep, a duck, and a rooster!

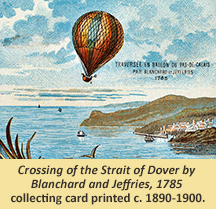

The discovery of hydrogen around the same time allowed for additional experimentation, and shortly after the Montgolfier brothers’ demonstrations, Jacques Charles launched an unmanned hydrogen-filled balloon. In the following months, a number of aviation firsts were achieved – the first tethered human flight, the first free flight with human passengers, and in January of 1785, the first balloon crossing of the English Channel. This daring feat was carried out by Jean-Pierre Blanchard, an inventor and fame-seeking “aeronaut,” and John Jeffries, an American doctor who financed the operation in exchange for accompanying Blanchard on the flight. Despite a rocky partnership and difficulties during the voyage, their flight was a great achievement (Bristow 2010:23-25). Blanchard’s success led to a career as a professional balloonist in which he demonstrated balloon flight for crowds of onlookers. He capped off his international career with the first flight in the United States in January 1793 with President Washington in attendence (Holmes 2013:20). A newspaper article describing the event reads, "The celebrated aeronaut made his 45th voyage in a magnificent balloon from... the city of Philadelphia… amidst the acclamations of an immense concourse of spectators. His ascension was majestick; he saluted his terrestrial gazers with his flag…” (Columbian Centinel 1793:2).

The discovery of hydrogen around the same time allowed for additional experimentation, and shortly after the Montgolfier brothers’ demonstrations, Jacques Charles launched an unmanned hydrogen-filled balloon. In the following months, a number of aviation firsts were achieved – the first tethered human flight, the first free flight with human passengers, and in January of 1785, the first balloon crossing of the English Channel. This daring feat was carried out by Jean-Pierre Blanchard, an inventor and fame-seeking “aeronaut,” and John Jeffries, an American doctor who financed the operation in exchange for accompanying Blanchard on the flight. Despite a rocky partnership and difficulties during the voyage, their flight was a great achievement (Bristow 2010:23-25). Blanchard’s success led to a career as a professional balloonist in which he demonstrated balloon flight for crowds of onlookers. He capped off his international career with the first flight in the United States in January 1793 with President Washington in attendence (Holmes 2013:20). A newspaper article describing the event reads, "The celebrated aeronaut made his 45th voyage in a magnificent balloon from... the city of Philadelphia… amidst the acclamations of an immense concourse of spectators. His ascension was majestick; he saluted his terrestrial gazers with his flag…” (Columbian Centinel 1793:2).

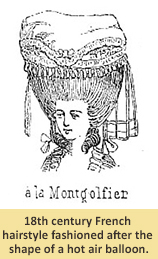

The public was fascinated by balloon flight, and a craze for all things balloon was firmly established. One resident of Paris wrote, “all one hears is talk of experiments, atmospheric air, inflammable gas, flying cars, journeys in the sky” (Heppenheimer 2001:9). The rage inspired clothing, jewelry, and just about every conceivable form of adornment for home or person. Parisian women even wore their hair “à la Montgolfier” (Lacroix 1876)!

The public was fascinated by balloon flight, and a craze for all things balloon was firmly established. One resident of Paris wrote, “all one hears is talk of experiments, atmospheric air, inflammable gas, flying cars, journeys in the sky” (Heppenheimer 2001:9). The rage inspired clothing, jewelry, and just about every conceivable form of adornment for home or person. Parisian women even wore their hair “à la Montgolfier” (Lacroix 1876)!

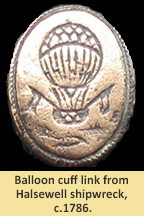

An artifact recently excavated by the Maryland State Highway Administration at Camp Stanton (18CH305) in Benedict, Maryland appears to be one such “ballooniana” object. This cuff link features a hydrogen-style balloon with two flags, possibly flying over a seascape. It has been suggested that this type of motif was commemorative of Blanchard and Jeffries’ crossing of the English Channel (Parker 2013). A nearly identical sleeve link was recovered from the Halsewell (Carter n.d.), a trade ship that was wrecked off the coast of England in 1786, just one year after the Channel crossing. Although the ballooning experiments occurred mainly in Europe, the craze quickly took hold in the newly formed United States as well. As Crouch (n.d.) explains, “If human beings could break the age-old chains of gravity, what other restraints might they cast off? The invention of the balloon seemed perfectly calculated to celebrate the birth of a new nation dedicated… to the very idea of freedom for the individual.”

An artifact recently excavated by the Maryland State Highway Administration at Camp Stanton (18CH305) in Benedict, Maryland appears to be one such “ballooniana” object. This cuff link features a hydrogen-style balloon with two flags, possibly flying over a seascape. It has been suggested that this type of motif was commemorative of Blanchard and Jeffries’ crossing of the English Channel (Parker 2013). A nearly identical sleeve link was recovered from the Halsewell (Carter n.d.), a trade ship that was wrecked off the coast of England in 1786, just one year after the Channel crossing. Although the ballooning experiments occurred mainly in Europe, the craze quickly took hold in the newly formed United States as well. As Crouch (n.d.) explains, “If human beings could break the age-old chains of gravity, what other restraints might they cast off? The invention of the balloon seemed perfectly calculated to celebrate the birth of a new nation dedicated… to the very idea of freedom for the individual.”

However, there is one piece of the puzzle that does not quite fit; the Camp Stanton site, where the cuff link was excavated, does not date to the late 18th century, but rather to the Civil War period. The camp was established in 1863 to recruit and train African Americans for the Colored Infantry Regiments of the Union Army. Early research on the cuff link suggested that it might be a military button related to the

However, there is one piece of the puzzle that does not quite fit; the Camp Stanton site, where the cuff link was excavated, does not date to the late 18th century, but rather to the Civil War period. The camp was established in 1863 to recruit and train African Americans for the Colored Infantry Regiments of the Union Army. Early research on the cuff link suggested that it might be a military button related to the  Balloon Corps (Sorensen-Mutchie 2013:4), a branch of the Army that provided aerial reconnaissance to Union troops. Records indicate that the Corps was operating in Charles County (Levinthal 2014), just a short distance from Camp Stanton, and although there is no apparent connection between the Balloon Corps and the US Colored Troops, it is possible that there was some interaction.

Balloon Corps (Sorensen-Mutchie 2013:4), a branch of the Army that provided aerial reconnaissance to Union troops. Records indicate that the Corps was operating in Charles County (Levinthal 2014), just a short distance from Camp Stanton, and although there is no apparent connection between the Balloon Corps and the US Colored Troops, it is possible that there was some interaction.

It is important to remember that no archeological site exists within a vacuum, however, and there are numerous possibilities for how this cuff link came to be in a field in southern Maryland. Did the owner of a nearby 18th century plantation lose his fashionable balloon cuff link long before Camp Stanton existed? Was an old cuff link repurposed at a later date? Or was an early ballooning motif recycled on a 19th century object? While we will never know the exact story behind the artifact, it illustrates just how momentous the development of flight really was and how the ability to fly has changed our world.

| References |

|

| Bristow, David L. |

| 2010 |

Sky Sailors: True Stories of the Balloon Era. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux. |

|

| Carter, David |

| n.d. |

Halsewell 1786. www.weymouthlunarsociety.org.uk/halsewell.htm, accessed January 24, 2014. |

|

| Columbian Centinel |

| 1793 |

M. Blanchard. www.rarenewspapers.com, accessed January 24, 2014. |

|

| Crouch, Tom D. |

| n.d. |

The Birth of the Balloon. www.airandspace.si.edu/collections/group/the-birth-of-the-balloon, accessed January 24, 2014. |

|

| Heppenheimer, T. A. |

| 2001 |

A Brief History of Flight From Balloons to Mach 3 and Beyond. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. |

|

| Holmes, Richard |

| 2013 |

Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air. New York: Pantheon Books. |

|

| Lacroix, Paul |

| 1876 |

The Eighteenth Century, Its Institutions, Customs and Costumes. France 1700-1789. New York: Scribner, Welford, and Armstrong. www.americanrevolution.org/clothing/frenchfashion.html, accessed January 24, 2014. |

|

| Levinthal, Aaron |

| 2014 |

Personal Communication. January 15, 2014. |

|

| Parker, Mark |

| 2013 |

Early to Rise. Western and Eastern Treasures Magazine, Vol. 47. |

|

| Sorensen-Mutchie, Nichole |

| 2013 |

Artifact Analysis: Military Balloon Button. Maryland State Highway Administration Cultural Resources Bulletin, Vol. 5, Issue 1. |

|