Snake Oil and Magic Potions: Fooling the Public with Cure-alls and Quackery

April 2014

By Erin Wingfield, MAC Lab Collections Assistant

One of the most widespread and colorful fraud schemes in early America came in the form of medicinal cure-alls. Promising to heal anyone from all kinds of ailments, these attractive and inexpensive remedies were eagerly purchased by customers. Besides being swindled out of their money, many patrons had no idea how dangerous these products really were and what they actually contained.

One of the most widespread and colorful fraud schemes in early America came in the form of medicinal cure-alls. Promising to heal anyone from all kinds of ailments, these attractive and inexpensive remedies were eagerly purchased by customers. Besides being swindled out of their money, many patrons had no idea how dangerous these products really were and what they actually contained.

The first proprietary medicines arrived from England in 1723 (Sellari 1975:66). A select few were rewarded with patents of royal favor, indicating they were used by the royal family. These became the most popular imported medicines, including Turlington’s Balsam of Life (Figure 1). After import restrictions related to the Revolutionary War, production of American-made medicines increased to fill public demand. These alternatives not only provided a feeling of nationalistic pride but were also less expensive than their English counterparts (Munsey 1970:65).

Collectively these products were referred to as nostrum remedium, ‘our remedy’, and patent medicines (Hagley 2014). Contrary to what the name would suggest, the majority of patent medicines were not actually patented. The patenting process required the manufacturer to list every ingredient in the product. Instead, creators would protect their medicines by registering the name or any unique marks related to the brand itself (Fike 1987:3, Munsey 1970:65).

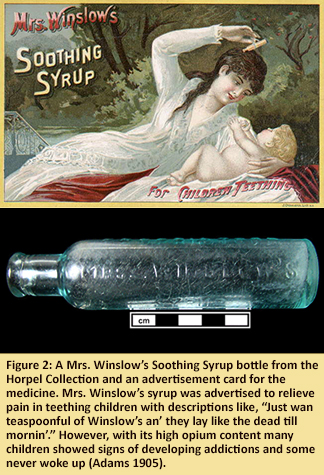

Patent medicines became popular among the poor as inexpensive alternatives to potentially suspicious doctors. These remedies were available without a prescription and simple enough for the average person  to understand. At the height of their popularity patent medicines appeared in numerous forms such as: balsams, syrups, extracts, tonics, sarsaparillas, cures, remedies, and bitters. These products claimed to cure anything and sometimes everything including: chills, fever, aches, pains, dysentery, liver complaints, cancer, consumption, indigestion, various bowel disorders, female complaints and many others. However, many of these so called medicines were simply combinations of vegetable extracts, water, sugar and alcohol. Others also included more harmful and addictive ingredients, including morphine, opium, and cocaine (Fike 1987:3). Many of these were even marketed for use with young children and infants (Figure 2).

to understand. At the height of their popularity patent medicines appeared in numerous forms such as: balsams, syrups, extracts, tonics, sarsaparillas, cures, remedies, and bitters. These products claimed to cure anything and sometimes everything including: chills, fever, aches, pains, dysentery, liver complaints, cancer, consumption, indigestion, various bowel disorders, female complaints and many others. However, many of these so called medicines were simply combinations of vegetable extracts, water, sugar and alcohol. Others also included more harmful and addictive ingredients, including morphine, opium, and cocaine (Fike 1987:3). Many of these were even marketed for use with young children and infants (Figure 2).

During the peak of the patent medicine era, 1880-1900, marketing and sales pitches were everywhere. Advertisements and testimonials promoting nostrums appeared in all sorts of publications, even medical journals. Publishers became dependent on this lucrative ad revenue and typically sided with medicine companies against any proposed legislation (Adams 1905, Hagley 2014). Medicine pitch men also began traveling from city to city selling their medicines. The most elaborate of these shows were similar to circuses with traveling wagons, live entertainment, exotic  costumes and music to gather the crowd. The Kickapoo Medicine Company was the largest of these organizations with as many as 75 shows touring on regular circuits (Munsey 1970:67). Patent medicines became so conventional that one of the most popular brands of Bitters, Hostetter’s, was even given to Civil War infantrymen to boost their spirits before battle (Sellari 1975:39).

costumes and music to gather the crowd. The Kickapoo Medicine Company was the largest of these organizations with as many as 75 shows touring on regular circuits (Munsey 1970:67). Patent medicines became so conventional that one of the most popular brands of Bitters, Hostetter’s, was even given to Civil War infantrymen to boost their spirits before battle (Sellari 1975:39).

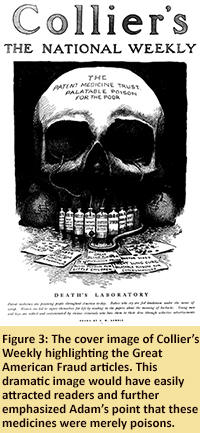

This began to change in 1905, when Samuel Hopkins Adams published a series of investigative articles in Collier’s Weekly entitled, “The Great American Fraud” (Figure 3). This was the first time the general public was exposed to any honest criticism of patent medicines. Adams described the secret ingredients included in nostums and their harmful effects, citing numerous examples. Readers were shocked by descriptions of opium-addicted children and young women dying from headache cures. Adams argued that unless legislation regulated the ingredients and marketing of patent medicines, people would continue to die from these deceptive poisons (Adams 1905, Munsey 1970:69).

Many believe the public attention gained from these publications caused the federal government to finally take action with the creation of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. This required all products containing alcohol, morphine, opium, cocaine, heroin, chloroform, cannabis or acetanilide to label their products as such. It also prohibited distributers from making misleading and fraudulent claims about the effectiveness of their drugs (Fike 1978:3, Lindsey 2014). After bad press and continued legislation, the market for patent medicines decreased dramatically and never recovered. However today, the flashy patent medicine era is still remembered through popular culture and historical reenactments.

| References |

|

| Adams, Samuel Hopkins |

| 1905 |

"The Great American Fraud". Collier’s Weekly 36.2. |

|

| Fike, Richard E. |

| 1987 |

The Bottle Book. Gibbs M. Smith Inc., Salt Lake City, UT. |

|

| Hagley Museum and Library |

| 2014 |

"History of Patent Medicine". Accessed March 26, 2014. http://www.hagley.org/online_exhibits/patentmed/history/history.html. |

|

| Lindsey, Bill |

| 2014 |

"Medicinal Bottles". Accessed March 21, 2014. http://www.sha.org/bottle/medicinal.htm. |

|

| Munsey, Cecil |

| 1970 |

The Illustrated Guide to Collecting Bottles. Hawthorne Books, New York, NY. |

|

| Sellari, Carlo and Dot |

| 1975 |

The Illustrated Price Guide of Antique Bottles. Country Beautiful, Waukesha, WI. |

|

| Image Sources |

|

| Figure 2 |

|

Winslow's Soothing Syrup Advertisement - http://www.sha.org/bottle/Typing/medicine/winslowstc.jpg |

|

| Figure 3 |

|

Death's Laboratory - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:DeathsLaboratory.gif |

|