Bavarian Black Buttons

May 2014

By Sara Rivers Cofield, MAC Lab Curator of Federal Collections

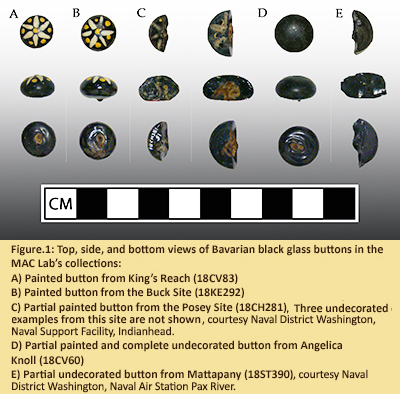

Behold the wonder that is the bulbous black glass Bavarian button! These buttons first came to my attention when the grant-funded website titled A Comparative Archaeological Study of Colonial Chesapeake Culture launched in 2009 and multiple sites had one or more of these distinctive nearly spherical glass buttons. Some of the buttons are painted with a yellow and white starburst-like design while others are plain (Figure 1). For the most part, the buttons recovered in the Chesapeake date to the 17th century.

Behold the wonder that is the bulbous black glass Bavarian button! These buttons first came to my attention when the grant-funded website titled A Comparative Archaeological Study of Colonial Chesapeake Culture launched in 2009 and multiple sites had one or more of these distinctive nearly spherical glass buttons. Some of the buttons are painted with a yellow and white starburst-like design while others are plain (Figure 1). For the most part, the buttons recovered in the Chesapeake date to the 17th century.

The earliest examples were found at Jamestown, and in one case eight black glass buttons were recovered along the breastbone of a burial, indicating their use on a doublet or jerkin that a man wore to his grave (Bly Straube, personal communication 2013). That was a rare and fortunate clue as to how the buttons were used, because 17th-century clothes were usually too valuable to bury with the dead.

Small bulbous buttons made of metal, glass, or thread over a wooden mold were very popular in the 17th century, and those who could afford fine clothing often had dozens of tightly-spaced buttons along the chest or sleeve of a single doublet, jerkin, coat, bodice, or waistcoat (Figure 2). The buttons served both as fasteners and as showy fashion accessories. The black glass buttons that have been found in Maryland all seem to date to the second half of the 17th-century. In the 18th century, buttons tended to flatten out and increase in size, so little spherical buttons fell out of style.

Small bulbous buttons made of metal, glass, or thread over a wooden mold were very popular in the 17th century, and those who could afford fine clothing often had dozens of tightly-spaced buttons along the chest or sleeve of a single doublet, jerkin, coat, bodice, or waistcoat (Figure 2). The buttons served both as fasteners and as showy fashion accessories. The black glass buttons that have been found in Maryland all seem to date to the second half of the 17th-century. In the 18th century, buttons tended to flatten out and increase in size, so little spherical buttons fell out of style.

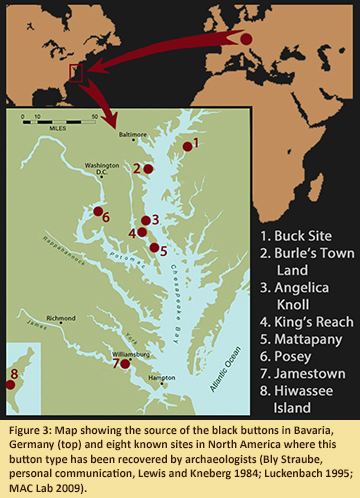

What makes these buttons extra special to archaeology is that once they were posted online, we started to hear from other people who found them (Figure 3). First, we were contacted by an archaeologist excavating a 17th-century glassworks in Bavaria where 80% of the artifacts recovered in a glass hut excavated in 2004 were black glass buttons.

Bavaria was a center of glass button and bead production because of its proximity to the necessary natural resources needed to make glass, and a lot of the goods were produced specifically for export (Florian Preiss, personal communication 2009; Dubin 1987:113). Elemental analysis of buttons from Jamestown matched the composition of the buttons recovered in Bavaria (Bly Straube, personal communication 2013), and it is likely that the Maryland black buttons came through the same trade networks.

But the life of the buttons did not always stop with export to European settlers. Painted black glass buttons have also been recovered on sites occupied by American Indians in the 17th century. The Posey site in Charles County, Maryland was occupied by a few American Indian families from ca. 1650-1680, and its artifacts include one painted button and three plain black buttons. That is not surprising since English settlers lived nearby, but it was unexpected to hear from an archaeologist in Tennessee about the exact same painted button being recovered at a 17th-century American Indian site on the Tennessee River called Hiwassee Island (Jon Marcoux, personal communication 2013; Lewis and Kneberg 1984: Plate 85). Since Europeans had not yet settled that far west, the Hiwassee Island button must have traveled through trade networks. So far, we don’t know if the buttons were imported for the Indian trade along with common glass trade beads, or Indians traded for the original clothing that fastened with these buttons. Either is plausible since beads and buttons were made at the same glass production sites, and European clothing was among the trade goods desired by American Indians.

But the life of the buttons did not always stop with export to European settlers. Painted black glass buttons have also been recovered on sites occupied by American Indians in the 17th century. The Posey site in Charles County, Maryland was occupied by a few American Indian families from ca. 1650-1680, and its artifacts include one painted button and three plain black buttons. That is not surprising since English settlers lived nearby, but it was unexpected to hear from an archaeologist in Tennessee about the exact same painted button being recovered at a 17th-century American Indian site on the Tennessee River called Hiwassee Island (Jon Marcoux, personal communication 2013; Lewis and Kneberg 1984: Plate 85). Since Europeans had not yet settled that far west, the Hiwassee Island button must have traveled through trade networks. So far, we don’t know if the buttons were imported for the Indian trade along with common glass trade beads, or Indians traded for the original clothing that fastened with these buttons. Either is plausible since beads and buttons were made at the same glass production sites, and European clothing was among the trade goods desired by American Indians.

The best thing about bulbous Bavarian black buttons though (other than the tongue twister opportunities), is that the more people look through their old collections and put photos and site information online, the more all archaeologists are able to turn the occasional lost button into an opportunity to explore how interconnected the Atlantic World was in the 17th century. By tracing a black button from its birth in Bavaria to its loss in the colonies or reuse for trade on American Indian sites, archaeology transforms these buttons from fashionable fasteners to direct evidence of important trade connections that developed between Europe and North America 400 years ago.

| References |

|

| Dubin, Lois Sherr |

| 1987 |

The History of Beads, from 30,000 B.C. to the Present. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishers, New York. |

|

| Lewis, Thomas M. and Madeline Kneberg |

| 1984 |

Hiwassee Island: An Archaeological Account of Four Tennessee Indian Peoples. The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, TN. |

|

| Luckenbach, Al |

| 1995 |

Providence 1649: The History and Archaeology of Anne Arundel County Maryland’s First European Settlement. The Maryland State Archives, Studies in Local History. |

|

| Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab (MAC Lab) |

| 2009 |

A Comparative Archaeological Study of Colonial Chesapeake Culture. Web resource: http://www.chesapeakearchaeology.org/Index.aspx, accessed April 30, 2014. |

|