Some Objects Lead an Interesting Life: A Tale of

Dr. Samuel Mudd's Tea and Coffee Service

October 2014

By Francis Lukezic, MAC Lab Conservator

President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in Washington D.C. by actor John Wilkes Booth on April 14, 1865. Booth fled and eventually stopped at the farm of Dr. Samuel Mudd, seeking treatment for his broken leg. For treating Booth’s leg and facilitating his escape, Dr. Mudd was imprisoned in Fort Jefferson, in the Dry Tortugas, Florida, from 1865 to 1869. During his imprisonment, Dr. Mudd became ill and received care from the prison warden’s wife. In gratitude, Dr. Mudd had the family’s tea and coffee service sent from their home in Waldorf, Maryland to Fort Jefferson, and gifted it to her. The set remained in southern Florida and eventually entered the collections of the National Park Service. The humid and salt-filled environment of southern Florida has not been kind to the tea and coffee service so it has returned to Maryland, temporarily, to undergo conservation treatment at the Laboratory. The treatment will consist of stabilizing deterioration and delicately cleaning the surface.

President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in Washington D.C. by actor John Wilkes Booth on April 14, 1865. Booth fled and eventually stopped at the farm of Dr. Samuel Mudd, seeking treatment for his broken leg. For treating Booth’s leg and facilitating his escape, Dr. Mudd was imprisoned in Fort Jefferson, in the Dry Tortugas, Florida, from 1865 to 1869. During his imprisonment, Dr. Mudd became ill and received care from the prison warden’s wife. In gratitude, Dr. Mudd had the family’s tea and coffee service sent from their home in Waldorf, Maryland to Fort Jefferson, and gifted it to her. The set remained in southern Florida and eventually entered the collections of the National Park Service. The humid and salt-filled environment of southern Florida has not been kind to the tea and coffee service so it has returned to Maryland, temporarily, to undergo conservation treatment at the Laboratory. The treatment will consist of stabilizing deterioration and delicately cleaning the surface.

The tea and coffee set was made by James Dixon & Sons, a prominent firm in Sheffield, England, founded in 1806, that manufactured a range of metal wares in a variety of metal alloys and plated surfaces (Scott 1980: 40). They were especially known for manufacturing objects out of Britannia metal. Britannia metal is a type of pewter and is an alloy consisting primarily of tin, with smaller quantities of antimony and copper (Selwyn 2004: 144). A large proportion of tin produced a metal that, when finished, mimicked the brilliance of silver. This gave the appearance of an expensive, highly desirable metal but was in reach of consumers of more modest means.

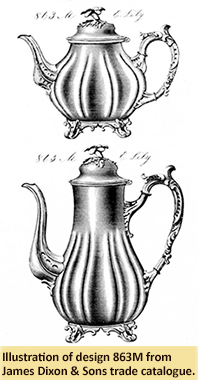

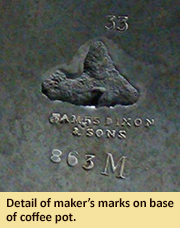

The tea and coffee set was made by James Dixon & Sons, a prominent firm in Sheffield, England, founded in 1806, that manufactured a range of metal wares in a variety of metal alloys and plated surfaces (Scott 1980: 40). They were especially known for manufacturing objects out of Britannia metal. Britannia metal is a type of pewter and is an alloy consisting primarily of tin, with smaller quantities of antimony and copper (Selwyn 2004: 144). A large proportion of tin produced a metal that, when finished, mimicked the brilliance of silver. This gave the appearance of an expensive, highly desirable metal but was in reach of consumers of more modest means.  Britannia metal was generally lead-free but some alloy recipes also employed a small amount of lead, which was added to facilitate the flow of liquid metal into a mould during the casting process (Conroy 2008: 77). The company changed their manufacturing signature and marks periodically over time. The marks stamped on the base of the tea and coffee pots indicates that the set was made sometime during 1842 to 1851 (Scott 1980: 224-225). These dates were further verified in a James Dixon & Sons trade catalogue from the same time period, that featured an illustration of the same design, with the pattern number 863M, which is also stamped on the base of the Dr. Mudd tea and coffee pots. The trade catalogue listed pattern 863M under “Best Britannia Metal” and provided the cost for each item. For example, the sugar basin with lid was 7 shillings and the cream jug was 4 shillings. It is not known when the Mudd family purchased the tea and coffee set. Prior to the American Civil War, the United States was James Dixon & Son’s leading export market (Scott 1980: 48).

Britannia metal was generally lead-free but some alloy recipes also employed a small amount of lead, which was added to facilitate the flow of liquid metal into a mould during the casting process (Conroy 2008: 77). The company changed their manufacturing signature and marks periodically over time. The marks stamped on the base of the tea and coffee pots indicates that the set was made sometime during 1842 to 1851 (Scott 1980: 224-225). These dates were further verified in a James Dixon & Sons trade catalogue from the same time period, that featured an illustration of the same design, with the pattern number 863M, which is also stamped on the base of the Dr. Mudd tea and coffee pots. The trade catalogue listed pattern 863M under “Best Britannia Metal” and provided the cost for each item. For example, the sugar basin with lid was 7 shillings and the cream jug was 4 shillings. It is not known when the Mudd family purchased the tea and coffee set. Prior to the American Civil War, the United States was James Dixon & Son’s leading export market (Scott 1980: 48).

A curious feature of the tea and coffee service is a fragmentary coating or plating that is visible on the exterior surface of each piece. The coating is noticeably thick, has a network of fine cracks in the surface, and appears crude compared to the surface of the base metal. To sort out the peculiar difference between the base metal and surface coating, an analytical tool called X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) Spectroscopy was utilized. XRF is a technique that identifies a material’s composition without having to remove a sample from the object. The results verified that the base metal is a Britannia metal alloy, consisting primarily of tin (80%) with small amounts of antimony (4.6%), lead (13.6%), and copper (0.9%). The fragmentary surface coating was also 80% tin but the other proportions were somewhat different, with 8.4% antimony, 7.6% lead, and 2.3% copper.

A curious feature of the tea and coffee service is a fragmentary coating or plating that is visible on the exterior surface of each piece. The coating is noticeably thick, has a network of fine cracks in the surface, and appears crude compared to the surface of the base metal. To sort out the peculiar difference between the base metal and surface coating, an analytical tool called X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) Spectroscopy was utilized. XRF is a technique that identifies a material’s composition without having to remove a sample from the object. The results verified that the base metal is a Britannia metal alloy, consisting primarily of tin (80%) with small amounts of antimony (4.6%), lead (13.6%), and copper (0.9%). The fragmentary surface coating was also 80% tin but the other proportions were somewhat different, with 8.4% antimony, 7.6% lead, and 2.3% copper.

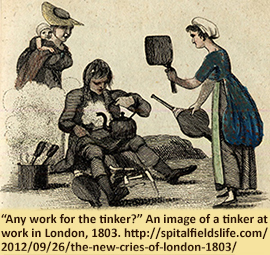

The results not only identified the composition but provided further insight in to a part of the life of the tea and coffee set that is not documented in the records. A plausible explanation of the fragmentary coating we see today is that it may represent an effort in the past to replate the surface of the set (Pouliot 2014). The metal oxidizes over time, dulling a once-bright surface. Replating would, for a time, create a shiny and pleasing surface. Itinerant tinkers, or travelling tinsmiths, were known for repairing and replating tin alloy metal objects, in addition to melting down metal objects no longer considered functional (Pouliot 2014).

The results not only identified the composition but provided further insight in to a part of the life of the tea and coffee set that is not documented in the records. A plausible explanation of the fragmentary coating we see today is that it may represent an effort in the past to replate the surface of the set (Pouliot 2014). The metal oxidizes over time, dulling a once-bright surface. Replating would, for a time, create a shiny and pleasing surface. Itinerant tinkers, or travelling tinsmiths, were known for repairing and replating tin alloy metal objects, in addition to melting down metal objects no longer considered functional (Pouliot 2014).

A tinker replated a metal object by either wiping molten metal on to the surface or dipping it into the molten metal (Corfield 1988: 34). Perhaps, the plating on the tea and coffee set was carried out by an itinerant tinker and is evidence of the owner’s desire to restore luster to the dull-grey surface and maintain use of valued domestic objects with a historic lineage.

| References |

|

| Conroy, Rachel |

| 2008 |

Hidden Histories: Uncovering the Secrets of James Dixon’s Britannia Metal Goods. Journal of the Antique Metalware Society, Vol. 16. |

|

| Corfield, Michael |

| 1988 |

Tin and Tinplate, Technology and Conservation. Modern Metals in Museums. London: Institute of Archaeology Publications. |

|

| James Dixon & Sons |

| n.d. |

James Dixon & Sons, Cornish Place, Sheffield, Merchants and Manufacturers of Silver, Best Sheffield Plate, Electro-plated, Nickel-Silver, and Britannia Metal Goods. |

|

| Pouliot, Bruno |

| 2014 |

Personal Communication. August 29, 2014. |

|

| Scott, Jack L. |

| 1980 |

Pewter Wares from Sheffield. Baltimore: Antiquary Press. |

|

| Selwyn, Lyndsie |

| 2004 |

Metals and Corrosion: A Handbook for the Conservation Professional. Ottawa: Canadian Conservation Institute. |

|