I LOVE Your Hair!

December 2014

By Edward Chaney, Deputy Director, MAC Lab

Spanish Fly. The world’s most infamous aphrodisiac. The very name conjures images of illicit affairs, foreign intrigues, and dens of iniquity. Ancient Egyptians used it for orgies. The Roman empress Livia, wife of Augustus Caesar, spiked her guests’ food with it in hopes they would commit a blackmail-able indiscretion. Madame du Pompadour, mistress of King Louis XV, mixed it with soap to pump up the passion in their affair. Even the legendary Marquis de Sade slipped it in chocolates and gave them to prostitutes–an action for which he was condemned to death (Prischmann and Sheppard 2002; Scales 2013).

Spanish Fly. The world’s most infamous aphrodisiac. The very name conjures images of illicit affairs, foreign intrigues, and dens of iniquity. Ancient Egyptians used it for orgies. The Roman empress Livia, wife of Augustus Caesar, spiked her guests’ food with it in hopes they would commit a blackmail-able indiscretion. Madame du Pompadour, mistress of King Louis XV, mixed it with soap to pump up the passion in their affair. Even the legendary Marquis de Sade slipped it in chocolates and gave them to prostitutes–an action for which he was condemned to death (Prischmann and Sheppard 2002; Scales 2013).

The origin of Spanish Fly, also known as “cantharides,” isn’t quite so sexy. It is made from cantharidin, an extremely toxic substance produced by blister beetles of the family Meloidae. Consumption and topical application of the dried and powdered bug carcasses goes back to antiquity, and interestingly, much of that use was medicinal. Hippocrates prescribed it for dropsy. The Chinese used it for ulcers, piles, and rabies. Others thought it cured ailments as varied as earaches, nausea, gout, bladder stones, gonorrhea, ringworm, rheumatism, obesity, and

The origin of Spanish Fly, also known as “cantharides,” isn’t quite so sexy. It is made from cantharidin, an extremely toxic substance produced by blister beetles of the family Meloidae. Consumption and topical application of the dried and powdered bug carcasses goes back to antiquity, and interestingly, much of that use was medicinal. Hippocrates prescribed it for dropsy. The Chinese used it for ulcers, piles, and rabies. Others thought it cured ailments as varied as earaches, nausea, gout, bladder stones, gonorrhea, ringworm, rheumatism, obesity, and  even demonic possession and hypochondria—for which the cure was no doubt worse than the “disease”! This is because merely touching a blister beetle can burn the skin, and eating more than trace amounts of cantharidin can destroy the stomach lining and lead to death. Although consumption of Spanish Fly is now banned, cantharidin is still used in some countries to treat warts, and it recently has been found to have anti-cancer properties (Kim et al. 2013; Prischmann and Sheppard 2002; Scales 2013).

even demonic possession and hypochondria—for which the cure was no doubt worse than the “disease”! This is because merely touching a blister beetle can burn the skin, and eating more than trace amounts of cantharidin can destroy the stomach lining and lead to death. Although consumption of Spanish Fly is now banned, cantharidin is still used in some countries to treat warts, and it recently has been found to have anti-cancer properties (Kim et al. 2013; Prischmann and Sheppard 2002; Scales 2013).

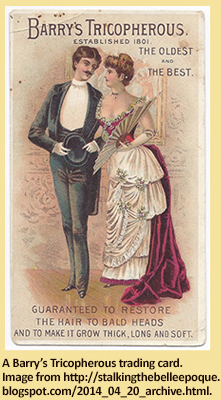

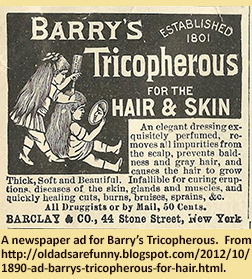

Evidence for the therapeutic use of cantharidin can be seen in a glass bottle excavated from a 19th-century well at the Federal Reserve site in Baltimore. The bottle was embossed with “BARRY’S TRICOPHEROUS FOR THE SKIN AND HAIR.” This elixir was first sold by a New York wigmaker, “Professor” Alexander Barry, in 1842 (although he claimed his father invented it in 1801). It was 97% alcohol, with the rest consisting of cantharidin and castor oil (hairquackery.com 2014). Like some modern shampoos, the “tingling sensation that tells you it’s working” when applied to skin (actually the disruption of transmembrane proteins holding cells together) was thought to cure baldness, make hair luxurious, and prevent graying and dandruff.

Evidence for the therapeutic use of cantharidin can be seen in a glass bottle excavated from a 19th-century well at the Federal Reserve site in Baltimore. The bottle was embossed with “BARRY’S TRICOPHEROUS FOR THE SKIN AND HAIR.” This elixir was first sold by a New York wigmaker, “Professor” Alexander Barry, in 1842 (although he claimed his father invented it in 1801). It was 97% alcohol, with the rest consisting of cantharidin and castor oil (hairquackery.com 2014). Like some modern shampoos, the “tingling sensation that tells you it’s working” when applied to skin (actually the disruption of transmembrane proteins holding cells together) was thought to cure baldness, make hair luxurious, and prevent graying and dandruff.  It also could be used to treat skin diseases and wounds, and heal ailing glands and muscles. It soon proved wildly popular—even the editor of Scientific American endorsed it, and Barry’s trading cards featuring drawings of beautiful women are now collector items (odysseysvirtualmuseum.com 2014). Amazingly, Barry’s Tricopherous is still sold as a hair product today – minus the Spanish Fly, of course. So if you have a bottle, don’t bother drinking it – eat some oysters instead!

It also could be used to treat skin diseases and wounds, and heal ailing glands and muscles. It soon proved wildly popular—even the editor of Scientific American endorsed it, and Barry’s trading cards featuring drawings of beautiful women are now collector items (odysseysvirtualmuseum.com 2014). Amazingly, Barry’s Tricopherous is still sold as a hair product today – minus the Spanish Fly, of course. So if you have a bottle, don’t bother drinking it – eat some oysters instead!