The Badge of a US Cavalry Officer

April 2015

By Nichole Doub, MAC Lab Head Conservator

During the 2002 excavation of the Chinatown area in Historic Deadwood, South Dakota, a small copper alloy button was recovered. This button, only 2.3 cm in diameter and weighing 3.3g, is the badge of a US Cavalry officer (Figure 1). The button features the Great Seal device of the United States, an eagle grasping an olive branch in one talon and arrows in the other. This cavalry button is distinctive in that a shield is displayed on the bird’s chest, bearing the letter “C”. Shortly after the US Congress created the Cavalry in 1855, the use of letters to denote military branch on enlisted men’s buttons was stopped. Officers, however, continued to use this style of button until the standardization of all uniform buttons in 1902 (Tice 1997: 133).

During the 2002 excavation of the Chinatown area in Historic Deadwood, South Dakota, a small copper alloy button was recovered. This button, only 2.3 cm in diameter and weighing 3.3g, is the badge of a US Cavalry officer (Figure 1). The button features the Great Seal device of the United States, an eagle grasping an olive branch in one talon and arrows in the other. This cavalry button is distinctive in that a shield is displayed on the bird’s chest, bearing the letter “C”. Shortly after the US Congress created the Cavalry in 1855, the use of letters to denote military branch on enlisted men’s buttons was stopped. Officers, however, continued to use this style of button until the standardization of all uniform buttons in 1902 (Tice 1997: 133).

During the 1860s and 1870s, the American drive for expansion into the western frontier was met with violence as settlers struggled with Native Americans over land and opposing ways of life. In an effort to put an end to these conflicts, Congress created the Indian Peace Committee charged with preventing future Indian uprisings and wars. (Oman 2002: 35) The primary method employed by this committee was to establish treaties that would force tribes to give up existing lands and move further west into reservations. The 1868 Treaty of Laramie (Figure 2) was one such effort between the US Government and the Sioux, which established the Black Hills as part of the Great Sioux Reservation and for exclusive use by the Sioux people.

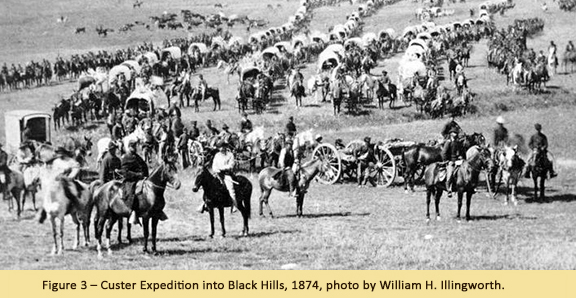

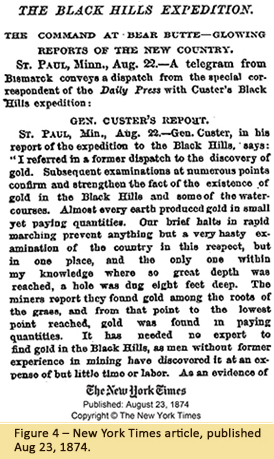

Only six years later, the US Government sent a military expedition into the Black Hills region to establish the location of a new Army fort and to survey the area’s natural resources. The two month expedition was led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer with the accompaniment of the 7th Cavalry, over 1000 men and more than 100 wagons, together with horse and cattle (Cozzens 2004: 176) (Figure 3). On August 15, 1874, Custer wrote to Assistant Adjutant General of the Department of Dakota describing the presence of gold in the Black Hills, “the miners report that they found gold among the roots of the grass… gold was found in paying quantities… men without former experience in mining have discovered it at an expense of but little time or labor” (Cozzens 2004:166). Custer’s reports were conveyed by the New York Times (Figure 4) and other reporters with the expedition soon had reports of gold covering the headlines of newspapers across the nation.

Only six years later, the US Government sent a military expedition into the Black Hills region to establish the location of a new Army fort and to survey the area’s natural resources. The two month expedition was led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer with the accompaniment of the 7th Cavalry, over 1000 men and more than 100 wagons, together with horse and cattle (Cozzens 2004: 176) (Figure 3). On August 15, 1874, Custer wrote to Assistant Adjutant General of the Department of Dakota describing the presence of gold in the Black Hills, “the miners report that they found gold among the roots of the grass… gold was found in paying quantities… men without former experience in mining have discovered it at an expense of but little time or labor” (Cozzens 2004:166). Custer’s reports were conveyed by the New York Times (Figure 4) and other reporters with the expedition soon had reports of gold covering the headlines of newspapers across the nation.

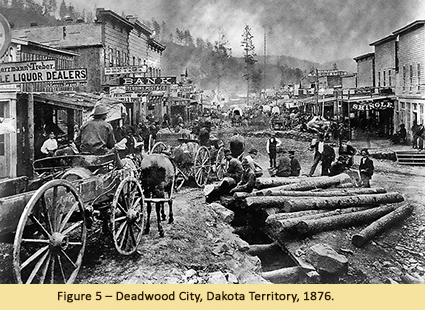

By the fall of 1874, white and Chinese prospectors flocked to the Black Hills without regard to the Treaty of Laramie. The new town of Deadwood, South Dakota would become the most prominent settlement and later an icon of the American Wild West (Figure 5). ;With this invasion into Sioux territory, violent  encounters between whites and Native Americans increased and the settlers demanded protection from the US Army. This led to the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877, and the famous Battle of Little Bighorn and the defeat of Custer and the 7th Cavalry.

encounters between whites and Native Americans increased and the settlers demanded protection from the US Army. This led to the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877, and the famous Battle of Little Bighorn and the defeat of Custer and the 7th Cavalry.

One year following Little Bighorn, Fort Meade was established to provide protection to the gold mining area around Deadwood and the associated transportation routes. The 7th Cavalry was stationed at Fort Meade during the height of hostilities. Years later, on December 29, 1890, the 7th Cavalry was responsible for the infamous Massacre at Wounded Knee, which would herald the end of the American Indian Wars.

In some ways, this button can be said to represent both the beginning and end of the American West.

| References |

|

| Cozzens, P. |

| 2004 |

Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars, 1865-1890. Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books. |

|

| National Archives |

| n.d. |

Web resource: http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/american_originals/sioux.html accessed March 18, 2015. |

|

| New York Times |

| 1874 |

"The Black Hills expedition". Web resource: http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=9800E2D7143BEF34BC4B51DFBE66838F669FDE accessed March 24, 2015. |

|

| Oman, Kerry R. |

| 2002 |

"The Beginning Of The End The Indian Peace Commission Of 1867~1868". Great Plains Quarterly. Paper 2353. |

|

| South Dakota State Historical Society |

| 2008 |

Deadwood Chinatown Excavation Site Report. South Dakota State Historical Society Archaeological Research Center. |

|

| Tice, Warren K. |

| 1997 |

Uniform Buttons of the United States, 1776-1865. Gettysburg: Thomas Publications. |

|