August 2016

By Caitlin Shaffer, MAC Lab Conservator

How many times have you walked by a monument in a park and not given it a second thought? You might see it as just some civic decor, or maybe you occasionally glance at the accompanying plaque. Even as people who are interested in history, we often don’t fully recognize the rich stories behind these objects.

How many times have you walked by a monument in a park and not given it a second thought? You might see it as just some civic decor, or maybe you occasionally glance at the accompanying plaque. Even as people who are interested in history, we often don’t fully recognize the rich stories behind these objects.

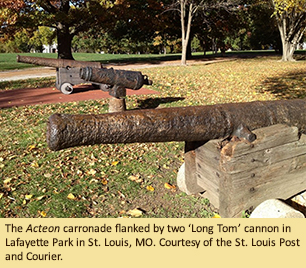

For the past six months, conservators at the MAC Lab have been treating a type of iron cannon, called a carronade, which came to us from Lafayette Park in St. Louis, Missouri. Centered between two ‘Long Tom’ cannon, the smaller carronade looked rather unimpressive, especially after years of being exposed to the elements. Conservation of the cannon includes stripping off multiple coats of old deteriorated paint, soaking it in solution to remove damaging salts that have accumulated during its lifetime, and applying new protective coatings. These steps will stabilize the cannon and restore it to its former good looks so it can return to its place of honor in the park.

Why go to all the trouble for just another cannon?

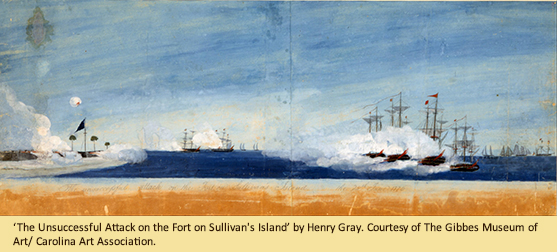

The story begins in June 1776, at a time when there was great upheaval in the American colonies. As our Declaration of Independence was being drafted and debated, the British were eager to make an example of rebellious colonies. With their sights set on the city of Charleston, the British fleet moved to attack Fort Moultrie. The area had been hastily fortified and was only completed on the seaward side, so when nine Men-of-War moved into firing position, Charlestonians feared that the ships would “knock the town about our ears” (Stokely 2016). As the bombardment began, three British frigates took advantage of the cover fire, and sailed past the fort to attack its vulnerable sides. However, unfamiliar with the area, the frigates quickly ran aground on sand banks. Two of the ships were eventually floated free, but the third, the Acteon, had to be abandoned and was set afire before the retreat. The Acteon went down with her guns, and the day ended in an embarrassing defeat for the British.

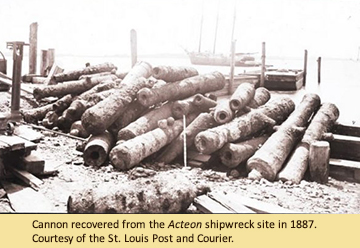

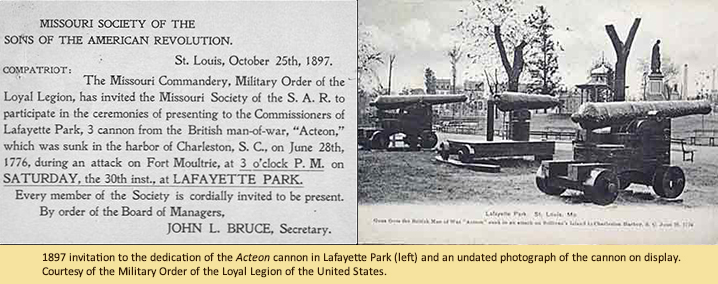

More than 100 years later, in 1887, a British steamer ship struck an obstruction as it entered Charleston harbor. The incident was reported to authorities, and a diver sent to investigate discovered a heap of cannon and shot. Brought up by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the cannon were ultimately used as rip rap in jetties around the city (Niermeyer 2005). Three of the cannon were saved from this fate by being purchased at auction by the Military Officers of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS) – a veterans’ organization with a large collection of historical artifacts at the Missouri Commandery in St. Louis (Niermeyer 2005). A decade after recovering them, MOLLUS donated the cannon to Lafayette Park, where they have remained until today.

More than 100 years later, in 1887, a British steamer ship struck an obstruction as it entered Charleston harbor. The incident was reported to authorities, and a diver sent to investigate discovered a heap of cannon and shot. Brought up by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the cannon were ultimately used as rip rap in jetties around the city (Niermeyer 2005). Three of the cannon were saved from this fate by being purchased at auction by the Military Officers of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS) – a veterans’ organization with a large collection of historical artifacts at the Missouri Commandery in St. Louis (Niermeyer 2005). A decade after recovering them, MOLLUS donated the cannon to Lafayette Park, where they have remained until today.

The carronade type cannon, developed by the Carron Company of Falkirk, Scotland, was innovative in its design. Although they were most effective at close range, they were smaller, and therefore far lighter, than long guns, making them easier to transport. They also required fewer men to operate (Munday 1998). The British Navy recognized these merits and began using carronades alongside traditional long guns when they were introduced to the market in 1779 (Gooding 1930).

But how could a carronade manufactured in 1779 go down with a ship in 1776? There is speculation among researchers that this gun from the Acteon is, in fact, an early carronade prototype referred to in Carron Company literature as one of ‘the new light constructed guns’ that was in development between 1776 and 1778 (Hicks 2015, Watters 2005). While it is unknown how it came to be on the Acteon, this particular gun has had an interesting role in both Revolutionary history and cannon technology – two facts that certainly make it worth stopping for a closer look.

| References |

|

| Gooding, S. James |

| 1930 |

An Introduction to British Artillery in North America. Alexandria Bay, NY: Museum Restoration Service. |

|

| Hicks, Brian |

| 2015 |

How Did Revolutionary War-Era Cannons from Charleston End Up in St. Louis? www.postandcourier.com/article/20150706/PC16/150709634, accessed July 22, 2016. |

|

| Munday, John |

| 1998 |

Naval Cannon. Buckinghamshire, UK: Shire Publications Ltd. |

|

| Niermeyer, Douglas |

| 2005 |

Revolutionary War Cannons of The HMS Actaeon Displayed at the Lafayette Park in St. Louis, Missouri. www.suvcw.org/mollus/art036.htm, accessed 22 July 2016. |

|

| Stokely, Jim |

| 2016 |

Fort Moultrie and the Battle of Sullivans Island. www.ccpl.org/content.asp?id=15742&catID=6047&action=detail, accessed July 22, 2016. |

|

| Watters, Brian |

| 2005 |

Carron Company. www.falkirklocalhistorysociety.co.uk/home/index.php?id=107, accessed July 22, 2016. |

|