December 2016

By Edward Chaney and Alexandra Glass,

MAC Lab Deputy Director and University College London

It’s December, a time when the pleasant scent of holiday candles fills the air. But in the 18th century, candles and lamps had a more practical purpose – lighting the home – and the result was not necessarily a pleasing aroma. The most common source of indoor light was animal fat, or tallow. Candles made of tallow were cheaper than all others, and their performance reflected it. They were excessively smoky, tended to sag as the temperature rose, dripped a lot, and perhaps worst of all, gave off a “greasy” odor (Caspall 1987). Other substances, such as beeswax and whale oil, were more agreeable to burn, but also much more expensive.

It’s December, a time when the pleasant scent of holiday candles fills the air. But in the 18th century, candles and lamps had a more practical purpose – lighting the home – and the result was not necessarily a pleasing aroma. The most common source of indoor light was animal fat, or tallow. Candles made of tallow were cheaper than all others, and their performance reflected it. They were excessively smoky, tended to sag as the temperature rose, dripped a lot, and perhaps worst of all, gave off a “greasy” odor (Caspall 1987). Other substances, such as beeswax and whale oil, were more agreeable to burn, but also much more expensive.

Early European settlers of North America quickly discovered a plant – the bayberry or wax myrtle (Myrica sp.) – that could be made into a superior candle. Robert Beverley, in his 1705 history of Virginia, noted that in the region “grows the Myrtle, bearing a Berry, of which they make a hard brittle Wax …Of this they make Candles, which are never greasie to the Touch, nor melt with lying in the hottest Weather: Neither does the Snuff of these ever offend the Smell, like that of a Tallow-Candle.” To produce the wax, berries were collected in the late autumn and boiled in pots. The floating oil was skimmed off, allowed to harden, then boiled again. The result was a transparent greenish wax. A small amount of tallow was often added to this when making candles (Gill and Powers 1981). Depending on the bayberry species, it could take 6 to 15 pounds of berries to make a pound of wax. Bayberry candles produced a good light, and had a strawberry-like aroma (Caspall 1987).

Early European settlers of North America quickly discovered a plant – the bayberry or wax myrtle (Myrica sp.) – that could be made into a superior candle. Robert Beverley, in his 1705 history of Virginia, noted that in the region “grows the Myrtle, bearing a Berry, of which they make a hard brittle Wax …Of this they make Candles, which are never greasie to the Touch, nor melt with lying in the hottest Weather: Neither does the Snuff of these ever offend the Smell, like that of a Tallow-Candle.” To produce the wax, berries were collected in the late autumn and boiled in pots. The floating oil was skimmed off, allowed to harden, then boiled again. The result was a transparent greenish wax. A small amount of tallow was often added to this when making candles (Gill and Powers 1981). Depending on the bayberry species, it could take 6 to 15 pounds of berries to make a pound of wax. Bayberry candles produced a good light, and had a strawberry-like aroma (Caspall 1987).

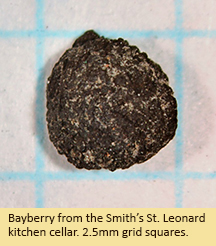

In 2011, JPPM archaeologists excavated a kitchen cellar at the Smith’s St. Leonard site, which was occupied between 1711 and 1754. The cellar was filled with trash and building debris sometime in the 1740s or 1750s, probably when the kitchen was being renovated. While examining charred plant remains recovered there, Alex Glass found something that archeobotanist Justine McKnight identified as a bayberry.

In 2011, JPPM archaeologists excavated a kitchen cellar at the Smith’s St. Leonard site, which was occupied between 1711 and 1754. The cellar was filled with trash and building debris sometime in the 1740s or 1750s, probably when the kitchen was being renovated. While examining charred plant remains recovered there, Alex Glass found something that archeobotanist Justine McKnight identified as a bayberry.  Interestingly, the 1754 probate inventory of John Smith, the last resident owner at the site, includes 16 pounds of myrtle wax. Thomas Jefferson, who was always on the hunt for bayberry candles (preferably tallow-free), was told by his supplier that “Myrtle Wax is only bought at Market in small Quantities of 4 to 10 lb. from the Country people” (Monticello 2016). This might indicate that Smith was producing small amounts of wax on his plantation to sell to candlemakers. However, his inventory also lists 1.5 pounds of wicks and 5 candle molds, so the wax Smith made was probably used to produce his own candles. Given that he had a large house to illuminate, and bayberry candles were second only to whale oil in cost, home candle production made economic sense.

Interestingly, the 1754 probate inventory of John Smith, the last resident owner at the site, includes 16 pounds of myrtle wax. Thomas Jefferson, who was always on the hunt for bayberry candles (preferably tallow-free), was told by his supplier that “Myrtle Wax is only bought at Market in small Quantities of 4 to 10 lb. from the Country people” (Monticello 2016). This might indicate that Smith was producing small amounts of wax on his plantation to sell to candlemakers. However, his inventory also lists 1.5 pounds of wicks and 5 candle molds, so the wax Smith made was probably used to produce his own candles. Given that he had a large house to illuminate, and bayberry candles were second only to whale oil in cost, home candle production made economic sense.

Bayberry candles fell out of favor in the 19th century, but they are still made, and have long been associated with the Christmas season. So burn one this December, think of John Smith and Thomas Jefferson, and be grateful that electric lights don’t run on tallow!

| References |

|

| Beverley, Robert |

| 1968 |

(1705) The History and Present State of Virginia. Dominion Books, Charlottesville, VA. |

|

| Caspall, John |

| 1987 |

Fire and Light in the Home Pre-1820. Antique Collectors’ Club, Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK. |

|

| Gill, Harold and Lou Powers |

| 1981 |

Candlemaking. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report #33. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA. |

|

| Monticello |

| 2016 |

Candles. www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/candles. Website accessed 11/29/2016. |

|