Curator's Choice 2017

"Taking the discipline" at St. Inigoes Plantation: A Cilice from Priest's Point

January 2017

By Laura E. Masur,

Boston University and 2015 Gloria S. King Fellow

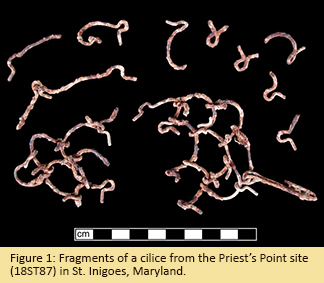

In the 1980s, archaeologists uncovered a curious metal object near the foundation of the Jesuit residence at Priest’s Point, St. Inigoes, Maryland. Originally described as a metal bedspring fragment (Dinnel 1984:13, 30), the object has now been identified as a cilice (Figure 1). A cilice is an object made of metal wire with sharp, inward-pointing tines, traditionally used or worn by faithful Catholics as a form of self-punishment. The term cilice is derived from Cilicia, a province in modern-day Turkey known for goats whose hair was used to make hair shirts, also worn for penitential purposes (Brandão and Nassaney 2008:484-485).

In the 1980s, archaeologists uncovered a curious metal object near the foundation of the Jesuit residence at Priest’s Point, St. Inigoes, Maryland. Originally described as a metal bedspring fragment (Dinnel 1984:13, 30), the object has now been identified as a cilice (Figure 1). A cilice is an object made of metal wire with sharp, inward-pointing tines, traditionally used or worn by faithful Catholics as a form of self-punishment. The term cilice is derived from Cilicia, a province in modern-day Turkey known for goats whose hair was used to make hair shirts, also worn for penitential purposes (Brandão and Nassaney 2008:484-485).

The cilice from Priest’s Point is a series of connected U-shaped iron wires, forming a net that measures at least 15 cm long and 6 cm wide. Each U-shaped wire terminates in a loop and exposed tine. There is a hook attached to the end, suggesting that the cilice was originally longer and may have been worn around the thigh (Figure 2). This artifact bears many similarities to a cilice excavated from an eighteenth century context at Fort St. Joseph, a French mission, garrison, and trading post in Michigan (Brandão and Nassaney 2008).

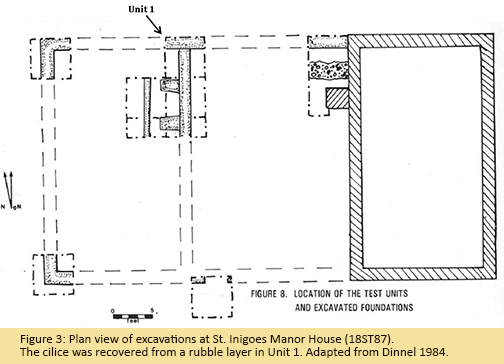

The Priest’s Point cilice was excavated from a layer of brick and mortar rubble associated with an 1872 fire and subsequent demolition at the St. Inigoes manor house (Figure 3). Other artifacts in this layer included wrought and cut nails, whiteware, a nineteenth-century figurine fragment, and green, aqua, and blue-green glass. The fire and demolition layer is located directly above the intact builder’s trench (Field Notes for 18ST87, Unit 1, Stratum C; 8-16-1983). This context suggests that the cilice was in or near the structure at the time of the 1872 fire, and probably fell from the second story priests’ residence (see schematic of “St. Inigos” from Georgetown Launinger Library, Maryland Province Archives, Box 15, Folder 3).

The Priest’s Point cilice was excavated from a layer of brick and mortar rubble associated with an 1872 fire and subsequent demolition at the St. Inigoes manor house (Figure 3). Other artifacts in this layer included wrought and cut nails, whiteware, a nineteenth-century figurine fragment, and green, aqua, and blue-green glass. The fire and demolition layer is located directly above the intact builder’s trench (Field Notes for 18ST87, Unit 1, Stratum C; 8-16-1983). This context suggests that the cilice was in or near the structure at the time of the 1872 fire, and probably fell from the second story priests’ residence (see schematic of “St. Inigos” from Georgetown Launinger Library, Maryland Province Archives, Box 15, Folder 3).

The twelve-room structure, probably built by English Jesuit Father James Ashby during the 1740s, was located at the confluence of the St. Mary’s River and St. Inigoes Creek (Treacy 1889:137-38). It served as the residence of numerous missionaries who managed St. Inigoes, a 2000-acre property purchased by the Jesuits in 1637. While most of the property was rented as tenant farms between the seventeenth and early twentieth centuries, Jesuit priests and brothers also lived on the property and managed a “home farm” or plantation. In addition, it was home to Jesuit novices for a short time at the beginning of the nineteenth century (Carroll 1815:114).

Self-mortification allows the faithful to share in the suffering of Christ, and is done as a form of penance, or to resist bodily temptations. This practice was common among Jesuit missionaries throughout the world during the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries. Despite their otherwise sumptuous apparel, a Jesuit in eighteenth century Asia reported that they could nonetheless “wear the hair-shirt and cilice, after the manner of numerous holy missionaries” (le Gobien 1706:234, quoted in Alberts 2014:103). In certain circumstances, self-mortification was also introduced to lay people. For example, in seventeenth century China, Jesuits encouraged penitential practices such as self-mortification among followers (Brockey 2008:396-397). These practices were so frequent among indigenous people of New France during the late seventeenth century that some Jesuits disapproved of their violence, believing it was associated with “diabolical tendencies” (Greer 2005:123). European artifacts used in self-mortification (whips, hair shirts, and “iron girdles”) were introduced to native populations in order to moderate this practice (Greer 2005:123).

Documentary sources do not, however, suggest that self-punishment was a common practice among lay people in Maryland. In his early nineteenth century diary, Jesuit Brother Joseph Mobberley relates a story about a Jesuit practicing self-mortification at St. Inigoes. At some point during the mid-eighteenth century, one of the Jesuits would regularly “take the discipline” in an old barn. When she was a girl, an enslaved cook named Granny Sucky interrupted this act, asking “her good master not to be so cruel to himself” (Mobberley 1995:7). The Jesuit whipped her in retribution, after which Granny Sucky “determined never to care much about his self-cruelties in the future” (Mobberley 1995:7). It is clear that this Jesuit believed self-mortification was an essential spiritual practice, and resorted to external violence in order to resist what he probably understood as temptation. Nonetheless, the enslaved African community, many of whom were baptized Catholics (see Beitzell 1959:76), apparently did not share his views about the necessity of self-mortification.

Documentary sources do not, however, suggest that self-punishment was a common practice among lay people in Maryland. In his early nineteenth century diary, Jesuit Brother Joseph Mobberley relates a story about a Jesuit practicing self-mortification at St. Inigoes. At some point during the mid-eighteenth century, one of the Jesuits would regularly “take the discipline” in an old barn. When she was a girl, an enslaved cook named Granny Sucky interrupted this act, asking “her good master not to be so cruel to himself” (Mobberley 1995:7). The Jesuit whipped her in retribution, after which Granny Sucky “determined never to care much about his self-cruelties in the future” (Mobberley 1995:7). It is clear that this Jesuit believed self-mortification was an essential spiritual practice, and resorted to external violence in order to resist what he probably understood as temptation. Nonetheless, the enslaved African community, many of whom were baptized Catholics (see Beitzell 1959:76), apparently did not share his views about the necessity of self-mortification.

The depositional context indicates that the cilice was almost certainly used by a Jesuit novice or priest. At the time of the 1872 fire, it was either curated in the manor house (you can imagine it tucked away in an old closet), or was regularly used by one of the house’s inhabitants. This, and the account referenced by Brother Mobberley, indicates that self-punishment was likely practiced at St. Inigoes over several centuries, and by several different methods. It also indicates that while certain practices were meant to be kept private, they did periodically come to light on the large plantation.

We can also infer that although self-flagellation and the wearing of a cilice was practiced among clergy stationed at St. Inigoes, it was less often encouraged, or was simply unpopular among enslaved Africans. This reflects differences in missionary attitudes in New France and Maryland, and the agency of enslaved Africans to resist the Jesuits’ imposition of religion (see Finn 1974: 77-81).

| References |

|

| Alberts, Tara |

| 2014 |

Conflict and Conversion: Catholicism in Southeast Asia, 1500-1700. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

|

| Beckett, Edward F. |

| 1996 |

“Listening to Our History: Inculturation and Jesuit Slaveholding.” Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits 28 (5):1–48. |

|

| Beitzell, Edwin Warfield |

| 1959 |

The Jesuit Missions of St. Mary’s County, Maryland. Abell, MD: St. Mary’s County Bicentennial Commission. |

|

| Brandão, José António, and Michael S. Nassaney |

| 2008 |

“Suffering for Jesus: Penitential Practices at Fort St. Joseph (Niles, Michigan) During the French Regime.” The Catholic Historical Review 94 (3):476–9 |

|

| Brockey, Liam Matthew |

| 2008 |

Journey to the East the Jesuit Mission to China, 1579-1724. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. |

|

| Bueton, Cara, Roby Fields, and Mike Smolek |

| 1983 |

“18ST87 Manor House Field Notes.” On file at the Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory. |

|

| Carroll, John. Personal Letter |

| 1815 |

“Letter of Bishop Carroll to Mr. Charles Plowden, at Stonyhurst, near Blackburne, Lancashire,” January 5. Woodstock Letters, Volume 10 (1881), Number 2, pp. 112-114. |

|

| Dinnel, Katherine J. |

| 1984 |

“Archeological Excavations at St. Inigoes Manor House, 18ST87, St. Mary’s County, Maryland.” Report presented to Naval Electronics Systems Engineering Activity. St. Inigoes, MD. |

|

| Finn, Peter C. |

| 1974 |

“The Slaves of the Jesuits in Maryland.” Master’s Thesis, Washington, D.C: Georgetown University, Department of History. |

|

| Greer, Allan |

| 2005 |

Mohawk Saint Catherine Tekakwitha and the Jesuits. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. |

|

| Mobberley, Joseph P. |

| 1995 |

"Br. Mobberley's Diary: St. Inigo's Mission, Early 1800's." Ridge, MD. Transcribed by Gale Burwell from original at Georgetown University Special Collections. |

|

| Treacy, William P. |

| 1889 |

Old Catholic Maryland and Its Early Jesuit Missionaries. Swedesboro, NJ: St. Joseph’s Rectory. http://archive.org/details/oldcatholicmaryl00trea. |

|

| Zwinge, Joseph |

| n.d. |

“St. Inigos.” Folder 15:3. Maryland Province Archives of the Society of Jesus, Georgetown University Special Collections. |

|