Curator's Choice 2018

Clothed in Splendor: Mass-Produced Coffin Hardware of the 19th Century

May 2018

By Mari Hagemeyer, MAC Lab Intern Conservator

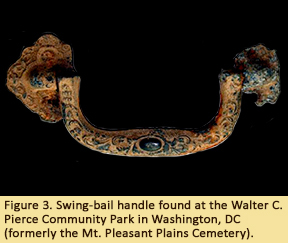

Sometime in the latter half of the 19th century, in an area of modern Dundalk, MD, known as Patapsco Neck, a small community of Methodists laid a young woman, aged between 30 and 39 years old, in her grave. Her congregation had dressed her body in a shroud or nightgown with three glass buttons, and affixed a hard rubber comb to her hair with a copper-alloy hairpin. Her white-painted coffin, which was interred in a domed brick vault, had a glass viewing panel with silver-plated cap lifters, and four elaborately molded, silver-plated swing bail handles. Over a century later, the wooden walls of her coffin no longer exist, but the silver-plated hardware affixed to it still remains (Erlandson 1998).

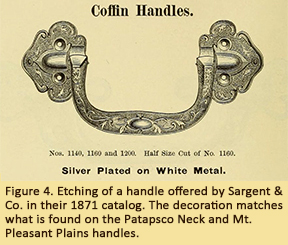

If this woman had lived a century prior, such an elegant casket would certainly indicate a person of some means. However, after the technological innovations of the Industrial Revolution, even elaborate hardware such as the handles on this coffin could be mass-produced out of cheap materials. Rather than being made of solid silver, or even silver plated over a more robust alloy like brass, these coffin handles were made of silver plated over “white metal”, a cheap alloy whose composition varied, but tended to include tin, antimony, and arsenic (Springate 2016).

Of course, for their intended use, white metal handles were perfect: they held the coffin up just fine for the one time they were needed, and were eminently affordable. These particular handles, which appeared in an 1871 catalog by Sargent & Co., were listed as costing $6.00 per dozen, or just 50¢ apiece (Sargent & Co. 1871). In today’s dollars, that translates into only $9.50 per handle - something a middle-class family could certainly afford. Indeed, the very same handles were used on at least one casket in the Mt. Pleasant Plains Cemetery, which served the historically disprivileged Black community in what is now Adams Morgan in Washington, DC (Mack 2013).

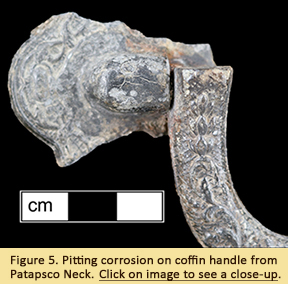

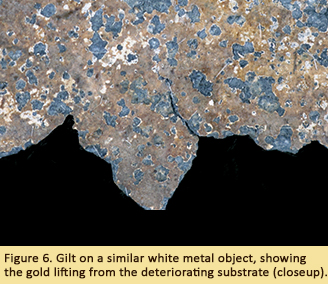

Although they functioned well for their intended use, white metal hardware do present some problems for conservators. White metal tends to become crumbly and brittle with age and deterioration, making it difficult to clean and conserve. The surface of such alloys can also become pitted and powdery, destroying the original shape of the object. Plating white metal with a less susceptible material like silver or gold can protect it, but if the plating is interrupted, the white metal will deteriorate as normal. With powdery corrosion under it instead of sound metal, the silver or gold plating is delicate and fragile, making conservation even more difficult.

Even though the cut corners that accompany mass-produced goods can prove frustrating for conservators, these products’ cheap availability makes them an excellent resource for understanding how ordinary people lived. The young woman buried in Patapsco Neck may have been as ordinary as they come—her grave isn’t even marked—but despite this, she still has a wealth of information that she can share with us.

| References |

| Erlandson, Kathy Lee |

| 1998 |

"Study Results and Discussion: Burials." In Archival and Archaeological Investigations at the Patapsco Neck Methodist Meeting House Site, 18BA443, Baltimore County, Maryland. Maryland Historical Trust, 1998, pp. 78-87. |

|

| Mack, Mark, and Mary Belcher |

| 2013 |

The Archaeological Investigation of Walter C. Pierce Community Park and Vicinity, 2005-2012: Report to the Public, May 2013. http://walterpierceparkcemeteries.org, 2013, pp. 83-86. |

|

| Sargent & Co. |

| 1871 |

"Price List and Illustrated Catalog of Hardware", Manufactured and For Sale by Sargent & Co., New York”, Sargent & Co., 1871, p. 274. |

|

| Springate, Megan E. |

| 2016 |

"Introduction." In Coffin Hardware in Nineteenth-century America. Vol. 5. Routledge, 2016, p. 13. |

|