Decade Ring

August 2019

By Laura Masur, Catholic University and 2015 Gloria S. King Fellow

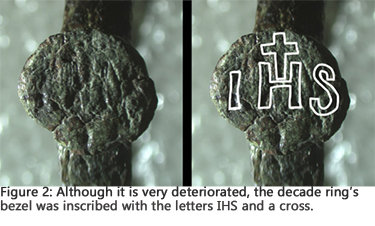

The ring pictured here is made of copper alloy, with ten small knobs protruding from the exterior of the band (Figure 1). Its flat bezel is inscribed with an insignia reading “IHS,” a Greek abbreviation of the name of Jesus (Figure 2). These characteristics indicate the ring would have been used to pray a decade of the Roman Catholic rosary.

The ring pictured here is made of copper alloy, with ten small knobs protruding from the exterior of the band (Figure 1). Its flat bezel is inscribed with an insignia reading “IHS,” a Greek abbreviation of the name of Jesus (Figure 2). These characteristics indicate the ring would have been used to pray a decade of the Roman Catholic rosary.

This ring was found during metal detecting in Lower Marlboro, Calvert County, in a field adjacent to the eighteenth-century Grahame House. Charles Grahame, for whom the house was named, purchased the property from Christian Smith in 1755. A house existed on the property before 1732, but it is unclear whether this was the Grahame House or another house on the property (Parish 1971). The ring was found about 300-400 feet from the house near brick fragments, buttons, farm tools, and an assortment of coins. These coins included a gold 1684 King Charles half guinea and a 1777 Spanish silver real (Charles Gilroy, pers. comm., June 18, 2019).

Although evidence is limited, these artifacts suggest that the ring was buried during the colonial period. There are two possible explanations for the ring’s archaeological context. First, it may have been deposited near a residence that preceded the construction of the  Grahame house. Second, the area may have been part of the colonial plantation landscape, including agricultural outbuildings or the residence of indentured servants or enslaved Africans associated with the Smith or Grahame households. The use of the site probably transitioned through time; it is impossible to know whether the ring was associated with the Smith or Grahame families or earlier households. While the object was clearly intended to be used in covert Roman Catholic prayers, the end of its use life remains a mystery. The ring may have been lost, or intentionally buried or discarded.

Grahame house. Second, the area may have been part of the colonial plantation landscape, including agricultural outbuildings or the residence of indentured servants or enslaved Africans associated with the Smith or Grahame households. The use of the site probably transitioned through time; it is impossible to know whether the ring was associated with the Smith or Grahame families or earlier households. While the object was clearly intended to be used in covert Roman Catholic prayers, the end of its use life remains a mystery. The ring may have been lost, or intentionally buried or discarded.

Christian devotional prayers associated with the Virgin Mary and counted on strings of beads were developed as early as the twelfth century in Germany and were used in a variety of popular practices. These and other devotions to the Virgin Mary, popular in pre-Reformation England, were forbidden after 1538. Jesuits in sixteenth-century England “repackaged” and standardized prayers surrounding the rosary, organizing devotees into Confraternities or Societies of the Rosary. A variety of manuals, including Jesuit Father Henry Garnet’s  1593 book The Society of the Rosary, provided instructions for these prayers: a meditation on 15 mysteries, each through the prayer of one Pater Noster (Our Father) and ten Aves (Hail Marys) (Dillon 2003; see also McClain 2003).

1593 book The Society of the Rosary, provided instructions for these prayers: a meditation on 15 mysteries, each through the prayer of one Pater Noster (Our Father) and ten Aves (Hail Marys) (Dillon 2003; see also McClain 2003).

While a full rosary contained enough beads to pray five “decades” (10 Hail Marys and one Our Father), single-decade rosaries were also used. These rosaries often contained, in addition to the beads, a cross or crucifix and a plain ring (Figure 3). The ring was moved between fingers to keep track of the number of decades that had been prayed (Bigger 1914). A decade ring or “thumb rosary” was most likely used in a similar way. These rings were made of gold, silver, copper alloys, and lead. One author argues that they originated in the Basque region of Spain, where they were worn in particular for nighttime prayers (McGuire 1954:103-104). These rings took on new meaning in England and Ireland, where they could be easily hidden and used covertly for prayer (McIntosh 2011).

Numerous decade rings have been identified in England through the Portable Antiquities scheme. One ring is nearly identical to the ring from Lower Marlboro (Noon 2011). On the bezel, there is a cross inscribed above “IHS” and three nails which evoke Christ’s crucifixion. Its production date is estimated as 1500-1800, and a similar copper alloy ring (Figure 4) was produced around 1600-1800. Although many of these rings bear the “IHS” christogram, the circular knobs used to count Hail Marys make this class of artifact distinct from “Jesuit” rings, a common find at American Indian sites in colonial New France and occasionally in the British colonies (e.g., Mercier 2011).

Its production date is estimated as 1500-1800, and a similar copper alloy ring (Figure 4) was produced around 1600-1800. Although many of these rings bear the “IHS” christogram, the circular knobs used to count Hail Marys make this class of artifact distinct from “Jesuit” rings, a common find at American Indian sites in colonial New France and occasionally in the British colonies (e.g., Mercier 2011).

Praying the rosary was a common practice among Roman Catholic inhabitants of Maryland and neighboring colonies. The practice was encouraged by Jesuit priests, who acted as missionaries in the colony and organized rosary societies among Catholics (see Hardy 1993:331-332). Rosary beads have been excavated from a variety of archaeological contexts in Jamestown and St. Mary’s City as well as other archaeological sites (e.g., Lapham 2001; Middleton and Miller 2008). Many of these rosaries contain about ten stone or glass beads, representing the Hail Mary prayers. Almost all rosary beads from the Chesapeake are disarticulated, which suggests that they were strung on an organic material that decomposed over time. Rosary rings are far less common; the object featured here is the only one of its kind found in Maryland or the surrounding region.

References to rosaries rarely made their way into documentary sources in Maryland. In one unusual account from 1640, a Maryland colonist requested “Ave Maria beads” from a Jesuit missionary. Instead of using them to pray, he ground up and smoked the powder in his tobacco pipe. The Jesuits recounting this tale were sure to include details on the man’s subsequent gruesome death, which resulted from the festering wound of a large fish bite (Foley 1878:380-381).

| References |

|

| Bigger, F. J. |

| 1914 |

Single-Decade Rosaries. Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society, 8(4), 244–246. |

| |

| Dillon, A. |

| 2003 |

Praying by number: The Confraternity of the Rosary and the English Catholic Community, c. 1580-1700. History, 88(291), 451–471.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-229X.00273 |

|

| Foley, H. |

| 1878 |

Records of the English Province of the Society of Jesus: Historic facts illustrative of the labours and sufferings of its members in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Vol. 3. Retrieved from http://archive.org/details/recordsofenglish00fole |

|

| Hardy, B.B. |

| 1993 |

Papists in a Protestant age: The Catholic gentry and community in colonial Maryland, 1689-1776. Unpublished Dissertation, University of Maryland. |

|

| Lapham, H. A. |

| 202011 |

More Than “A Few Blew Beads”: The Glass and Stone Beads from Jamestown Rediscovery’s 1994-1997 Excavations. The Journal of the Jamestown Rediscovery Center, Vol. 1. |

|

| McClain, L. |

| 2003 |

Using What’s at Hand: English Catholic Reinterpretations of the Rosary, 1559–1642. Journal of Religious History, 27(2), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9809.00169 |

|

| McGuire, E. A. |

| 2011 |

1954 Old Irish Rosaries. The Furrow, 5(2), 97–105. |

|

| McIntosh, Frances |

| 2011 |

DUR-1B73E3: A Post Medieval Finger Ring. https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/435929, accessed July 16, 2019. |

| |

| Mercier, C. |

| 2011 |

“Jesuit” Rings in Trade Exchanges Between France and New France: Contribution of a Technological Typology to Identifying Supply and Distribution Networks. Northeast Historical Archaeology, 40(1), 21–42. https://doi.org/10.22191/neha/vol40/iss1/2 |

| |

| Middleton, A. P., & Miller, H. M. |

| 2008 |

John Lewgar and the St. John’s Site: The Story of Their Role in Creating the Colony of Maryland Maryland Historical Magazine, 103(2), 132–165. |

| |

| Noon, Stuart |

| 2011 |

LANCUM-CE9AE3: A Post Medieval Finger Ring. https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/446034, accessed July 16, 2019. |

| |

| Parish, P. |

| 1971 |

Grahame House (National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form No. CT-10). Annapolis, MD: Maryland Historical Trust.

https://mht.maryland.gov/secure/medusa/PDF/Calvert/CT-10.pdf, accessed July 16, 2019. |

|

|