Curator's Choice 2020

Brass in Pocket A Button Legacy

January 2021 By Heather Rardin Rovardi, Conservator

In 2017, an archaeological survey and excavations were carried out on the Brumbaugh-Kendle-Grove (BKG) Farmstead in Washington County, Maryland. The site was slated for demolition as part of an expansion project for the Hagerstown Regional Airport.

The Farmstead had been occupied from its establishment in the second half of the 18th century until 1997, after which the site was managed by the Board of County Commissioners of Washington County (AECOM 2019:2.11).

A variety of buttons were recovered during the excavation, among which was a small brass shank button unearthed in an agricultural-related feature within the west yard (AECOM 2019.8.52). The Connecticut state seal and the letters “CONNECTICUT” and “QUI TRANST. SUST.” (see Figure 3) can clearly be seen on the obverse face, and “SCOVILL MF’G CO. WATERBURY'' are visible on the reverse.

A variety of buttons were recovered during the excavation, among which was a small brass shank button unearthed in an agricultural-related feature within the west yard (AECOM 2019.8.52). The Connecticut state seal and the letters “CONNECTICUT” and “QUI TRANST. SUST.” (see Figure 3) can clearly be seen on the obverse face, and “SCOVILL MF’G CO. WATERBURY'' are visible on the reverse.

Archaeologists from AECOM researched and identified the button as a Civil War military button created by the Scovill Manufacturing Company of Waterbury, Connecticut. “QUI TRANST. SUST.” is short for “Qui Transtulit Sustinet”, which is the state motto of Connecticut. In Latin, it means “he who transplanted continues to sustain” (Hughes and Lester 1991:723). The backstamp indicates that the button was made between 1850 and 1865 (Tice 1997:32-25) and worn by a Connecticut Regiment soldier (AECOM 2019:8.52).

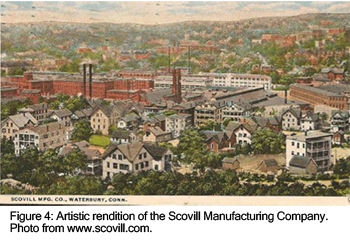

The Scovill Manufacturing Company of Waterbury, Connecticut began its life in 1802 as the Abel Porter and Company. Its founders were the brothers Abel and Levi Porter, Silas Grilley, and Daniel Clark (Luscomb 1967:174). The Grilley brothers were experts in casting pewter buttons and had operated a shop out of their home. Together with Porter and Clark, they created an industrial button-making operation (Tice 1997:25). Scrap metal was melted into ingots, alloyed with zinc to create brass, and formed into sheets which would be fed into large steel rollers turned by workhorses (Connecticut History 2020).

Access to British buttons was limited during the Napoleonic Wars, and this gave a boost to American manufacturers like Abel Porter and Company. The company responded to the demand and  began to produce military buttons, and by 1808, a water-powered mill had replaced the horse-turned rollers (Tice 1997:25). “Scovill” first appeared in the company name in 1811 when James Mitchell Lamson Scovill took over with his partners, Hayden and Leavenworth (Luscomb 1967:174). By the 1840s, the company had fine-tuned its gilding and engraving techniques, and by the dawn of the Civil War, the Scovill Manufacturing Company was producing “millions” of military buttons (Tice 1997:27-28, 32). The company, which

began to produce military buttons, and by 1808, a water-powered mill had replaced the horse-turned rollers (Tice 1997:25). “Scovill” first appeared in the company name in 1811 when James Mitchell Lamson Scovill took over with his partners, Hayden and Leavenworth (Luscomb 1967:174). By the 1840s, the company had fine-tuned its gilding and engraving techniques, and by the dawn of the Civil War, the Scovill Manufacturing Company was producing “millions” of military buttons (Tice 1997:27-28, 32). The company, which still exists today, expanded its offerings but continued to produce buttons for both domestic and international use into the second half of the 20th century (Luscomb 1967:174, Morito Scovill Americas 2020).

still exists today, expanded its offerings but continued to produce buttons for both domestic and international use into the second half of the 20th century (Luscomb 1967:174, Morito Scovill Americas 2020).

Curiously, the Scovill Manufacturing Company button is the only identified Civil War artifact that was

found in the excavations at the BKG Farmstead. Archaeologists at AECOM hypothesized that the button became loose and fell off of someone’s uniform as they came onto the property to look for supplies. Historical records support this, and indicate that a number of Connecticut regiments were either stationed in or moved through the area adjacent to the BKG Farmstead between 1861 and 1864 (AECOM 2019:8.52).

A single, datable artifact can be interesting on its own, and can provide valuable clues to the archaeologists who unearthed it. But when an artifact is viewed through the evolution of the techniques that humans used to make it and the legacy of human innovation, it becomes a richer and more engaging story.

References |

| AECOM |

2019

|

Phase I-III Archaeological Investigations, Brumbaugh-Kendle-Grove Farmstead (18WA496), Washington County, Maryland. Burlington, published by the author. Report accessed on December 14, 2020 at https://www.washco-md.net/wp-content/uploads/articulate_uploads/BKG_Website_20200715/assets/bkgfarmstead_phi-iii-final_report_20190326.pdf

|

| |

connecticuthistory.org

|

| 2020 |

Birth of the Brass Valley. Connecticuthistory.org: Business and Industry, Waterbury. Website accessed on December 14, 2020 at https://connecticuthistory.org/birth-of-the-brass-valley/.

|

Hughes, Elizabeth and Lester, Marion

|

1991

|

The Big Book of Buttons. New Leaf Publishers, Sedgwick. |

|

| Luscomb, Sally C. |

1967

|

The Collector's Encyclopedia of Buttons. Crown Publishers, Inc., New York

|

| Morito Scovill Americas |

2020

|

History. Morito Scovill Americas. Website accessed on December 14, 2020 at http://www.scovill.com/about-us/history/ |

| |

|

| Tice, Warren K. |

1997

|

Uniform Buttons of the United States 1776-1865. Thomas Publications, Gettysburg.

|

| |

|

| |

|