Curator's Choice 2020

Getting a Handle on a Mystery

February 2020

By Sara Rivers Cofield, Curator of Federal Collections

This copper alloy object (Figure 1) was featured as an unidentified artifact in a 2002 public booklet about the NAVAIR site, and the authors of the booklet appealed to readers for help with identification (NAS PAX and JPPM 2002:8). Since then we have learned a lot about the object, including its original function, but surprisingly it has retained an air of mystery because we still don’t know how it got to the site or how the people who lived at NAVAIR used it.

This copper alloy object (Figure 1) was featured as an unidentified artifact in a 2002 public booklet about the NAVAIR site, and the authors of the booklet appealed to readers for help with identification (NAS PAX and JPPM 2002:8). Since then we have learned a lot about the object, including its original function, but surprisingly it has retained an air of mystery because we still don’t know how it got to the site or how the people who lived at NAVAIR used it.

In 2008 another 18th-century collection deposited at the MAC Lab turned out to hold the key to identifying the NAVAIR mystery artifact. The collection came from the Horne Point site in Dorchester County, Maryland where excavations of a house that burned down around 1770 yielded a nearly complete tea set of sugar tongs, mote spoon, and five teaspoons (Jull 1980). Upon seeing this set, it immediately became clear that the

NAVAIR object was an exact match to the teaspoon handle, right down to the engraved decoration (Figure 2). We now know what the artifact was made for, and how it was originally used, but that’s not the whole story.

In archaeology, context is everything, so while we care what an individual artifact is, the importance of that artifact can only be understood by seeing it as part of a larger assemblage of artifacts from a particular place. The Horne Point tea set was found near a 46’ x 22.6’ brick house foundation flanked by two chimneys. Artifact density was quite high and included high-end ceramics (Jull 1980). All evidence suggests that the teaspoons found there were part of a set that was used for tea service by a relatively well-to-do family.

By contrast, the NAVAIR site, located aboard the Naval Air Station Patuxent River in St. Mary’s County, was a low-density domestic artifact concentration. Archaeologists interpreted the site as having been occupied by a single family of poor tenants or slaves ca. 1750-1800. Extensive excavations conducted prior to a construction project revealed the remains of a probable cabin represented by a brick chimney and a rectangular pit located near the hearth for storing food and/or personal items (NAS PAX and JPPM 2002; Watts and Tubby 1998). Archaeologists researched comparable cabins to speculate that the NAVAIR structure consisted of one room, “about the size of a modern-day dining room,” possibly with a loft above and an addition (NAS PAX and JPPM 2002:2-3). Some fragments of teawares were found at the site, but most of the ceramics were low-quality earthenwares in utilitarian forms. The end of one

spoon is the only evidence of what was once a full tea service utensil set, and this was found in the bottommost layer of the rectangular pit (Feature 16).

spoon is the only evidence of what was once a full tea service utensil set, and this was found in the bottommost layer of the rectangular pit (Feature 16).

Interestingly, the subfloor pit, Feature 16, had a concentration of copper alloy objects, including buttons, buckles, a bridle boss, and a leather ornament for horse tack. Only 26 of the 6558 artifacts recovered at NAVAIR were copper alloy. Of those, 18 (69%) were found in Feature 16 even though the feature represents only 4.3% of the overall site assemblage. It is not generally advisable to judge a pit’s function by the soil used to fill it, but it is notable that the spoon handle, horse tack decorations, and three buttons were all found in the bottommost layer where they are more likely to represent stored artifacts instead of fill (Figure 3).

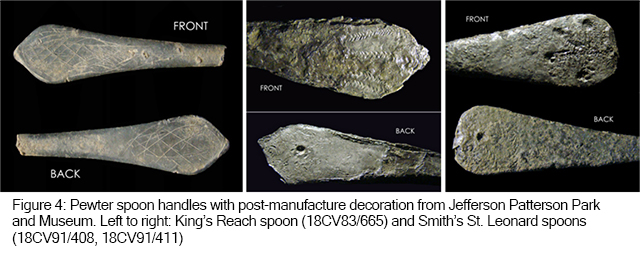

Spoon handles with carved designs have been found in subfloor pits at Kingsmill Plantation in Virginia, and the Kings Reach and Smith’s St. Leonard sites at Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum (Figure 4). Archaeologists still don’t know exactly why these spoons were engraved or how they were used, but motifs tend to resemble those found on carvings made in Africa and it is likely the spoons were decorated and used by slaves. They may represent divination tools or other objects of power such as Igbo ritual objects known as ofos (Samford 2007). Perhaps the NAVAIR spoon handle served such a purpose.

I don’t wish to suggest that slaves could not possibly have had tea sets or offered tea in their homes; some certainly would have. In the case of the NAVIAR teaspoon though, the location of the find, the lack of other parts of the tea set, and the assemblage of other potentially curated finds found at the bottom of Feature 16 all point to the likelihood that the spoon’s original function no longer applied. Whether the spoon handle was a divination tool imbued with supernatural properties, a pretty bauble kept because it was too interesting to throw away, a shiny thing used to distract a small child, or something else, from the perspective of archaeological interpretation, the interesting thing about this object is that someone who lived at the site thought enough of the spoon fragment to give it a new life. Whether they saved it from a trash pile, received it as a gift, or took it without permission, it must have meant something to someone to end up where it did.

Can you imagine walking in the shoes of a Maryland slave living in a small cabin in the second half of the 18th century? If so, imagine how you might have acquired this spoon handle. Why would you want it? Would you use it for something or just keep it? The likelihood that we will ever know with certainty why the spoon was reused and what people thought about it at the time is next to nil, but such artifacts offer a focal point for exploring possibilities.

References |

| Jull, Judy |

| 1980 |

Preliminary Report of Excavations at “Horne.” The Archaeology 32(1):1-41 |

NAS Patuxent River and Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum (NAS PAX and JPPM)

|

| 2002 |

A Late 18th Century Cabin Site in the Mattapany-Sewall Plantation. Environmental and Natural Resources Department, Naval Air Station, Patuxent River, Maryland.

|

Samford, Patricia

|

| 1981 |

Subfloor Pits and the Archaeology of Slavery in Colonial Virginia. The University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

|

| Watts, Gordon P., and Raymond Tubby |

| 1998 |

Phase III Archaeological Investigation of the NAVAIR Site 18ST642, Patuxent River Naval Air Station, Patuxent River, Maryland. On file at the Maryland Historical Trust. |