Curator's Choice 2020

Keeping Everything From Going Adrift

March 2020

By Alice Merkel, Collections Assistant

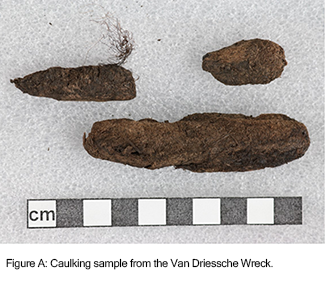

During a winter storm in 1998, the remains of a 19th-century shipwreck were exposed along the coast of Assateague Island and reported by local historian, Paul Van Driessche. The Van Driessche Wreck site  was revisited by the Maryland State Underwater Archaeologist to conduct more comprehensive documentation and surveying. Re-excavating the sand buried wreckage exposed coppered stained wood belonging to a two-masted schooner from the second half of the 19th century. With the keel, bow, and stern completely missing, as well as the complete lack of cargo, the functionality of the vessel is unknown but it may have been a merchant or whaling ship. The little remnants archaeologists were able to sample included caulking (Figure A) and fasteners made of brass and iron, one of which is a complete drifting bolt (Langley et al. 2002) (Figure B).

was revisited by the Maryland State Underwater Archaeologist to conduct more comprehensive documentation and surveying. Re-excavating the sand buried wreckage exposed coppered stained wood belonging to a two-masted schooner from the second half of the 19th century. With the keel, bow, and stern completely missing, as well as the complete lack of cargo, the functionality of the vessel is unknown but it may have been a merchant or whaling ship. The little remnants archaeologists were able to sample included caulking (Figure A) and fasteners made of brass and iron, one of which is a complete drifting bolt (Langley et al. 2002) (Figure B).

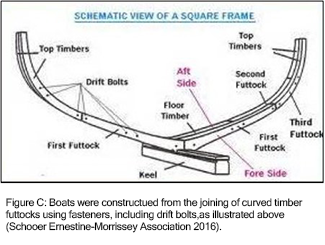

Before the mass production of weldable modern material like steel and aluminum revolutionized the maritime industry, large vessels were constructed of large wooden beams. In comparison with the modern boat building techniques of bolting or welding steel and aluminum fragments together, wooden beams were joined together to create the frame of the vessel using joiners or fasteners (Figure B). Caulking would then be driven between any joined pieces to both tighten the hull and reduce the movement between deck planks (Traditional Maritime Skills). Caulking is traditionally made mostly of oakum, loosely twisted hemp fibers saturated with tar, as well as other cotton and general rope fibers.

Metal fasteners came in the form of nails, bolt, and rivets made from wrought or cast iron, steel, copper, bronze, and brass. Bolts specifically are a fastener cut to length from a rod, most often made of iron, with the head and tip worked into shape by a hammer (Leigh Stone 1993: 33, 34).

The term drift refers to the difference between the diameters of the bored hole and the bolt that is driven

into it. These cylindrical steel and iron rods were joiners essential in ship construction prior to the invention of modern adhesives (Catsambis et al. 2014: 1119).

Modern adhesives not only require less force but also do not rust or have the potential to split wood like iron bolts do (Watts 2008).

A hole, 1/8 inch to 1/16 inch smaller in diameter than the fastener diameter would be bored in the beams and then the bolt would be hammered obliquely through the seams, creating a lateral connection between the two pieces (Ritter 1990: 5-132) (Figure C).

At times referred to as drift pins by the steel shipbuilding community, pins are headless and sometimes tapered compared to bolts. Widely used for areas with ample wood or areas that needed strong re-enforcement, drift bolts were prominently used due to their large size, durability, and the worked flattened head. The shaped, flat end of the drift bolt made it easier to drive the bolt directly into the beams (Leigh Stone 1993: 35). They were used to join rudders and leeboards, as well as broader boat frame features like the knees, ribs, and hull planking (McCarthy 2005: 180; Sheard 1998: 78).

References |

Catsambis, Alexis, Ben Ford and Donny L. Hamilton

|

| 2014 |

The Oxford Handbook of Maritime Archaeology. Oxford University Press.

|

| |

|

Langley, S.B.M., P. Van Driessche and J. Charles |

| 2002 |

Archaeological

Overview and Assessment of Maritime Resources in Assateague Island National

Seashore, Worcester County, Maryland & Accomack County, Virginia. Maryland Historical Trust.

|

Leigh Stone, David

|

| 1993 |

The Wreck Diver’s Guide to Sailing Ship Artifacts of the 19th Century. Underwater Archaeological Society of British Columbia. |

| |

|

| McCarthy, Michael |

| 2005 |

Ships’ Fastening: From Sewn Boat to Steamship. Texas

A&M University Press. |

| |

|

| Ritter, Michael R. |

| 1990 |

“Timber Bridges: Design, Construction, Inspection, and Maintenance”. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. |

| |

|

| Sheard, Bradley |

| 1998 |

Lost Voyages: Two Centuries of Shipwrecks in the Approaches to New York. Aqua Quest Publications, Inc.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Schooner Ernestina-Morrissey Association |

|

|

|

| 2016 |

“Futtocks and Frames Beginning to Take Shape”. http://www.ernestina.org/news/futtocks-and- frames-beginning-to-take-shape/ accessed 24 February 2020. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Traditional Maritime Skills |

|

|

|

| n.d. |

“Caulking Decks and Hulls”. http://www.boat-building.org/learn-skills/index.php/en/wood/ caulking-decks-and-hulls/ accessed 24 February 2020. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Watts, Simon |

|

|

|

| 2008 |

“Using Drift Pins”. https://www.woodworkersjournal.com/using-drift-pins/ accessed 21 February 2020. |

|

|

|

|

|