Curator's Choice 2020

A Tale of Two Fossils

December 2020 By Nathaniel Salzman, Village Manager

We don’t talk much about fossils in the Curator’s Choice. That’s because when people talk about fossils, they are usually referring to the geologic remains of plants and animals. Paleontologists study fossils to learn about the plants and animals from millions of years ago, while Maryland archaeologists study artifacts to learn about humans from, at most, thousands of years ago. But in some special cases, an item can be both a fossil and an artifact – when humans use or change a fossil, it becomes an artifact. This month’s artifact is a great example of that.

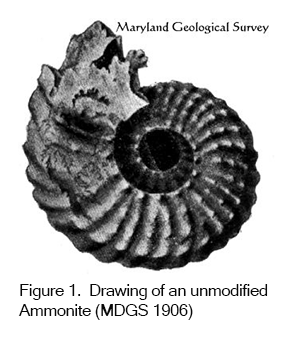

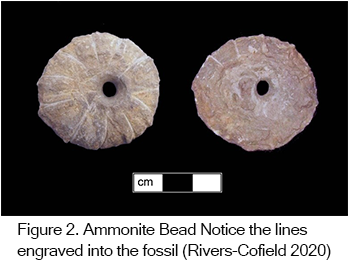

This Native American artifact may look like a simple bead, but it’s actually more than that. This bead is also a fossilized ammonite! Ammonites were a group of marine mollusks that lived millions of years ago and can be found in the Cretaceous formation throughout the Chesapeake (Clark 1906).

This fossilized ammonite became an artifact when it was changed and used by humans. Someone in the past most likely used this fossil as a bead by drilling a hole in the center and engraving the low spots on the fossil, called sutures, in order to make the demarcations more noticeable. Although some Native American groups in the West were using ammonites (Peck 2002), this artifact is the only known example of ammonite being used in the Chesapeake region despite its prevalence in the Cretaceous formation in this part of the country.

This fossilized ammonite became an artifact when it was changed and used by humans. Someone in the past most likely used this fossil as a bead by drilling a hole in the center and engraving the low spots on the fossil, called sutures, in order to make the demarcations more noticeable. Although some Native American groups in the West were using ammonites (Peck 2002), this artifact is the only known example of ammonite being used in the Chesapeake region despite its prevalence in the Cretaceous formation in this part of the country.

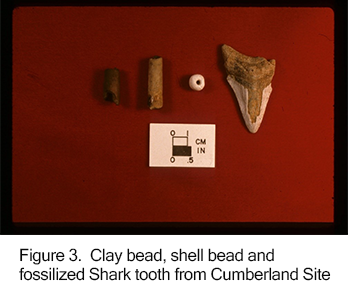

Another example of a fossil-turned-artifact is shark’s teeth, which have been used by Native Americans for thousands of years. Serrated shark’s teeth are thought to have been used to decorate Native American pipes (Stewart 1954), and many have been found with holes drilled into them so they could be used as beads. They have also been found in burial sites and were traded from Maryland all the way to Ohio (Colvin 2011).

Thinking about these two fossils-turned-artifacts leads to an interesting question: why don’t we find more ammonite beads, especially when we see many examples of shark’s teeth, being used for decoration in the region?

Thinking about these two fossils-turned-artifacts leads to an interesting question: why don’t we find more ammonite beads, especially when we see many examples of shark’s teeth, being used for decoration in the region?

We may never know for sure, but I think the answer probably comes down to the same reasons some gems are worth more than others today. In gemology, professionals have the “4C”s, which are used to grade gems: color, clarity, carat and cut. If we apply these qualities to ammonite versus shark’s teeth beads, I think we might have our answer.

1. Color: The ammonites found in the Chesapeake tend to be a brown color, like this month’s example. Shark’s teeth are generally a more attractive grey or black color.

2. Clarity: Though both shark’s teeth and ammonites are opaque, shark’s teeth have a natural sheen to them, which would most likely be enhanced with wear over time. In contrast, the ammonite’s sandstone texture would likely never get shiny, only darker.

3. Carat: Although many shark’s teeth found at archaeological sites may be small in size, Maryland is also home to megalodon teeth, which have been discovered at Adena sites on the Eastern Shore. These larger shark’s teeth beads could be the centerpiece of the necklace. However, all the ammonites found in Maryland tend to be relatively small.

4. Cut: Because ammonite is a sedimentary fossil, it’s easier to shape, which means two things. First, ammonite beads would not be as valuable because they take less time to shape, and second, they would be more fragile. Shark’s teeth, however, are more likely to survive intact and are less likely to break on the person wearing it.

And finally, because we talk about archaeology in the Curator’s Choice, I must add one final C.

5. Culture: Beyond the physical reasons described above, there may be some cultural reason for a preference for fossilized shark’s teeth compared to fossilized ammonites. It’s more difficult to hypothesize those cultural reasons, but my theory is that ammonites may not have been as popular because you could make something very similar – and probably easier! – out of clay.

| References |

| Clark, W.B. |

1906

|

“Volume VI, Maryland Geological Survey, Baltimore, MD.” Maryland Geological survey. Accessed 11/2/20 http://www.mgs.md.gov/geology/fossils/cretaceous.html

|

| |

Colvin H.George

|

| 2011 |

The Presence, Source and Use Of Fossil Shark Teeth From Ohio Archaeological Sites. Ohio Archaeologist Vol 61 No.4.

|

| Cumberland site Image cv171-00256s, Jefferson Patterson Park and museum. Accessed 11/18/20 https://apps.jefpat.maryland.gov/neh/DetailImages.aspx?ImageNo=cv171-00256s |

| |

Peck, Trevor

|

2002

|

Archaeologically Recovered Ammonites: Evidence for Long-Term Continuity in Nitsitapii Ritual. Plains Anthropologist. 47. 147-164

|

|

| |

|

| Stewart, T. Dale |

|

| 1954 |

"A Method for Analyzing and Reproducing Pipe Decorations". Quarterly Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Virginia 09:01 |

|

|

| Rivers-Cofield, Sarah (2020) Photo taken of 18KEX14-2 |