Curator's Choice 2020

What's the Point

July 2020

By Greg Pierce, Executive Director

Copper was an important resource for Native Americans in North America well before the arrival of Europeans. Native populations in the Chesapeake region obtained natural copper via trade with tribes in the Great Lakes and western North Carolina regions. Access to this copper was limited. This rarity, coupled with the metaphysical association of the metal, made the possession and display of copper indicative of elevated social status in native communities throughout the Chesapeake (Miller and Hamell 1986:325; Potter 2006:218). Numerous ethnohistorical accounts discuss the social value of copper items held in native society. The significant place this metal held in native Chesapeake cultures has also been confirmed archaeologically with the presence of copper gorgets and rolled copper beads in high-status burials in the region (Flick et al. 2012:148; Potter 2006; Potter 1993:217-219).

As Europeans realized the value of copper objects to native peoples, native trade systems saw an unprecedented influx of copper in the form of European pots, kettles, and scrap (Flick et al. 2012:148; Rivers Cofield 2009). These European trade items would have been repurposed by the Chesapeake Indians and cut into ornaments and eventually utilitarian items such as projectile points (Bradley 1987:130-5; Potter 1993:209). Ready access to copper by larger segments of native society devalued the commodity, diminishing its value as an item of prestige and distinction through time. Wider access, and increased supplies, of copper, ultimately impacted cultural and political institutions of the native tribes, leading to the weakening of the political authority of tribal leaders through the mid to late 17th century (Harmon et al. 1999: 150; Potter 2006). As copper became more readily available its use within native culture shifts from predominantly ornamental to more utilitarian applications (River Cofield 2009).

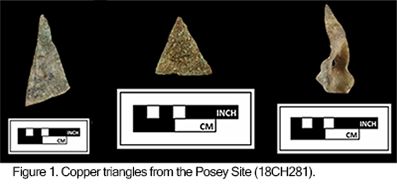

The Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab has three collections containing copper projectile points; the Posey, Heater’s Island, and Zekiah Fort sites. The Posey Site (18CH281) is a Native American settlement occupied between 1650 and 1680. Archaeological investigations recovered faunal remains, and large amounts of ceramics, lithics, hand-wrought nails, bottle glass, shell and glass beads, and brass and metal fragments including at least seven copper projectile points (Figure 1). Investigators believe the assemblage points towards a single occupation, with onsite activities including trade good manufacture and the repurposing of materials acquired through trade with Europeans (Harmon 1999:iii, 111, 144).

The Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab has three collections containing copper projectile points; the Posey, Heater’s Island, and Zekiah Fort sites. The Posey Site (18CH281) is a Native American settlement occupied between 1650 and 1680. Archaeological investigations recovered faunal remains, and large amounts of ceramics, lithics, hand-wrought nails, bottle glass, shell and glass beads, and brass and metal fragments including at least seven copper projectile points (Figure 1). Investigators believe the assemblage points towards a single occupation, with onsite activities including trade good manufacture and the repurposing of materials acquired through trade with Europeans (Harmon 1999:iii, 111, 144).

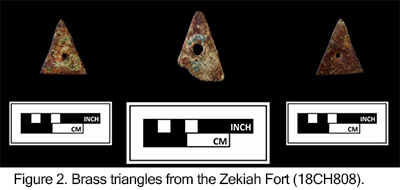

Zekiah Fort (18CH808), a fortified Piscataway settlement, was occupied from 1680 until c. 1695 (Flick et al. 2012:i). Archaeological investigations in the area began in the late 19th century. Modern investigations began in the 1950s and continued intermittently through 2011 when the Zekiah Fort site itself was located. The site’s assemblage includes native lithics and ceramics, and numerous European trade goods including ceramics, pipe fragments, glass beads, shot, gun flints, bottle glass, wrought iron nails, and 65 copper alloy artifacts (Figure 2) including four projectile points (Flick et al. 2012:i, 76-86, 149, 194-195).

Zekiah Fort (18CH808), a fortified Piscataway settlement, was occupied from 1680 until c. 1695 (Flick et al. 2012:i). Archaeological investigations in the area began in the late 19th century. Modern investigations began in the 1950s and continued intermittently through 2011 when the Zekiah Fort site itself was located. The site’s assemblage includes native lithics and ceramics, and numerous European trade goods including ceramics, pipe fragments, glass beads, shot, gun flints, bottle glass, wrought iron nails, and 65 copper alloy artifacts (Figure 2) including four projectile points (Flick et al. 2012:i, 76-86, 149, 194-195).

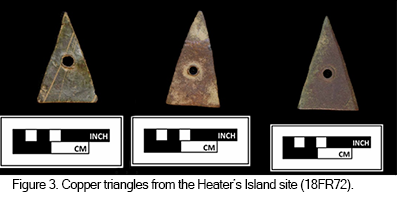

The Heater’s Island site (18FR72) was first identified on an aerial photograph in 1965, and archaeological investigations were undertaken in 1967 and 1970. Investigations revealed a fortified Piscataway settlement occupied from approximately 1699-1712. Numerous European trade goods were recovered from the archaeological investigations including ceramics, pipe fragments, glass beads, shot, gun flints, and 35 copper/brass triangular points (Figure 3), many of which are believed to be projectile points (Curry n.d.: 1, 9, 23).

The Heater’s Island site (18FR72) was first identified on an aerial photograph in 1965, and archaeological investigations were undertaken in 1967 and 1970. Investigations revealed a fortified Piscataway settlement occupied from approximately 1699-1712. Numerous European trade goods were recovered from the archaeological investigations including ceramics, pipe fragments, glass beads, shot, gun flints, and 35 copper/brass triangular points (Figure 3), many of which are believed to be projectile points (Curry n.d.: 1, 9, 23).

The material assemblages from these three sites include both European and native manufactured items. However, these items are differentially represented in each site. At the Posey site, while items of European manufacture were present, recovered artifacts were predominantly native in material and manufacture. By the 1680s, at Zekiah Fort, European manufactured goods were far more frequent. At Heater’s Island, dating to the end of the 17th and beginning of the 18th century, the material assemblage was overwhelmingly European (Frick et al. 2012:194). These differences give us some insight into the changing use of European goods, including copper, in native societies during the 17th and 18th centuries

Of interest here aren’t that native peoples were adopting European items and technologies, rather it was the manner in which these items were being used. Some of the European trade items were used alongside or as replacements for native technologies such as glass beads or smoking pipes. Other items would have initially complemented and eventually replaced similar technologies such as with the European firearm. In other instances we see European manufactured goods repurposed for activities for which they were never intended. Such is the case with our copper projectile points. These points were manufactured by native people who cut triangles from copper and brass kettles and scrap obtained through trade with Europeans. This process would have changed through time as native people became more familiar with the material. In our collection, the variety in the copper points from the Posey site indicates native experimentation with this type of manufacture. By the time the Heater’s Island was in use the copper points exhibited more uniformity in size and shape, suggesting an elevated level of comfort using this material to create projectile points.

Adaptations of European materials by native peoples were common throughout North America during the Protohistoric and Historic periods. Understanding when and how native people adopted and used European manufactured items has provided researchers insight into how indigenous cultures adopted or adapted to European influence. In the Chesapeake, the influx of copper items not only impacted native material culture but likely impacted indigenous cultural institutions as well. Who would have thought that we could learn so much from tiny little copper triangles?!

References |

| |

| Bradley, James W. |

1987

|

Evolution of the Onondaga Iroquois: Accommodating Change, 1500-1655. New York: Syracuse University Press. |

|

Curry, Dennis C.

|

| n.d. |

"We have been with the Emperor of Piscataway, at his fort:" Archaeological Investigation of the Heater's Island Site (18FR72). Draft manuscript (in preparation), Maryland Historical Trust, Crownsville, Maryland.

|

| |

Flick, Alex J., Skylar A. Bauer, Scott M. Strickland, D. Brad Hatch, and Julia A. King

|

| 2012 |

…a place now known unto them:” The Search for Zekiah Fort. St. Mary’s College of Maryland, St. Mary’s City, Maryland.

|

| Harmon, James, Grace S. Brush, David B. Landon, and Andrea Shapiro |

| 1999 |

Archaeological Investigations at the Posey Site (18CH281) and 18CH282 Indian Head Division, Naval Surface Warfare Center, Charles County, Maryland. Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum Occasional Papers (7). Maryland Historical Trust. |

| |

Kent, Barry C.

|

1984

|

Susquehanna’s Indians. Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, PA

|

| Miller, Christopher L., and George R. Hamell |

1986

|

A New Perspective on Indian-White Contact: Cultural Symbols and Colonial Trade. The Journal of American History 73(2):311-328.

|

| |

| Potter, Stephen R. |

1993

|

Commoners, Tributes, and Chiefs: The Development of Algonquian Culture in the Potomac Valley. Charlottesville, VA: The University of Virginia Press.

|

2006

|

Early English Effects on Virginia Algonquian Exchange and Tribute in the Tidewater Potomac. In Gregory A. Waselkov, Peter H. Wood, and Tom Hatley, eds., Powhatan’s Mantle: Indians in the Colonial Southeast, pp. 216-241. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. |

Rivers Cofield, Sara

|

2009

|

Copper Points from the Posey Site. Website accessed June 5, 2020 at https://jefpat.maryland.gov/Pages/mac-lab/curators-choice/2009-curators-choice/2009-06-copper-points-from-posey-site.aspx |

| |

| |