Curator's Choice 2021

Hoodoo Alive and Well in Mid-20th Century Annapolis

March 2021 By Rebecca Morehouse, State Curator

From 1990 to 1992, the Archaeology in Annapolis field school conducted excavations at the Maynard-Burgess House in Annapolis, Maryland. The Maynard-Burgess House was continuously owned and occupied by two African-American families. The Maynards built the house and members of that family lived there from 1850 to 1914. The property then transferred to the Burgesses, who lived there until 1990, when it was transferred to the Port of Annapolis (Mullins and Warner 1993: 1).

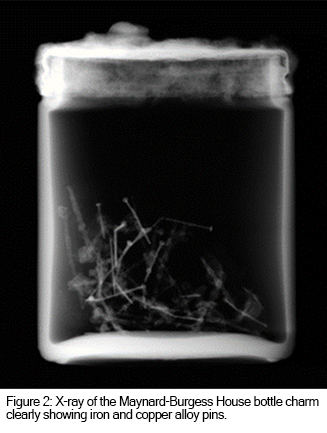

In 1991, during excavations around a recently removed 1940s addition to the back of the house, archaeologists recovered an interesting artifact. This artifact was a small, clear glass jar with a screw-top lid. The jar contained a fragment of red knitted fabric, which was pierced with several iron and copper alloy pins and what appeared to be several paper fragments (Figures 1 and 2). When recovered the jar was also filled with an unknown liquid. This liquid has been long since removed.

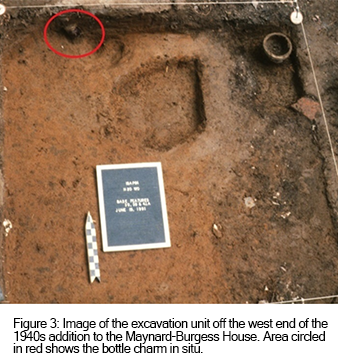

The excavation unit where the jar was found straddled the area where the western wall of the house addition once stood, with the western half of the unit on the exterior of the addition and the eastern half on the interior. The jar was recovered from the north wall of the western half of the unit indicating it was buried just outside the addition’s west wall. (Figure 3). The addition first appeared on the 1951 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, providing a date by when the addition must have been constructed. A neighboring excavation unit with an undisturbed layer directly under the addition yielded a 1941 penny. These two facts indicate that the addition was built sometime in the 1940s (Mullins and Warner 1993: 51). Further evidence of a mid-20th century date is the jar itself. The bottom of the jar has an embossed mark with an “F” in a hexagon that indicates it was manufactured between 1933 and 1971 by the Fairmount Glass Works in Indiana (Lockhart, et al. N.D.).

What is so interesting about this artifact is it has all the makings of the “witch bottles” most often found at 17th and 18th-century sites and associated with folk magic practices of European Americans, while also containing elements often found in African-American Hoodoo spiritual practice. The European witch bottle originated several hundred years ago as a protective charm used to ward off evil or as a countermeasure to redirect an evil spell back on the conjurer. Usually made using a glass bottle or ceramic jug, a witch bottle was filled with urine and sharp objects, such as pins or nails, and buried inverted at the entrance to a home or under a hearthstone (Becker 1980: 20-21; Merrifield 1987: 163-175). While a witch bottle could be used as a counter-curse, many that have been found in the United States have been interpreted more generally as protective charms for homes or other structures.

What is so interesting about this artifact is it has all the makings of the “witch bottles” most often found at 17th and 18th-century sites and associated with folk magic practices of European Americans, while also containing elements often found in African-American Hoodoo spiritual practice. The European witch bottle originated several hundred years ago as a protective charm used to ward off evil or as a countermeasure to redirect an evil spell back on the conjurer. Usually made using a glass bottle or ceramic jug, a witch bottle was filled with urine and sharp objects, such as pins or nails, and buried inverted at the entrance to a home or under a hearthstone (Becker 1980: 20-21; Merrifield 1987: 163-175). While a witch bottle could be used as a counter-curse, many that have been found in the United States have been interpreted more generally as protective charms for homes or other structures.

Hoodoo spiritual practice evolved in North America from various religious traditions of the enslaved Africans who were brought to this country. Spiritual bundles or bags called “mojos”, “hands”, or “tobys” were used to direct spirits, protect against evil, diagnose disease, or tell the future (Leone and Fry 1999: 380). These bundles or bags contained a variety of items, many similar to those found in European witch bottles. These items included crystals, pebbles, bones, gnarled roots, herbs, pins, needles, nails, and buttons. These bundles were frequently wrapped in red flannel or placed in red flannel bags (Cochrane 1999: 6; Leone and Fry 1999: 382). Versions of these mojo bags are still used today (Figure 4). There are also descriptions of these mojos being made in bottles which include pins, needles, red flannel, and urine or whiskey (Manning 2012: 134). The use of red flannel appears to be West African, although some English witch bottles contained a red felt heart. The color of the cloth was believed to increase the potency of the objects and the protective charm itself because of its association with blood, birth, death, sunrise, and sunset (Anderson 2002:130; Leone and Fry 1999: 382; Manning 2012: 134). Red was also believed to be the favorite color of spirits (Anderson 2002:130).

Hoodoo spiritual practice evolved in North America from various religious traditions of the enslaved Africans who were brought to this country. Spiritual bundles or bags called “mojos”, “hands”, or “tobys” were used to direct spirits, protect against evil, diagnose disease, or tell the future (Leone and Fry 1999: 380). These bundles or bags contained a variety of items, many similar to those found in European witch bottles. These items included crystals, pebbles, bones, gnarled roots, herbs, pins, needles, nails, and buttons. These bundles were frequently wrapped in red flannel or placed in red flannel bags (Cochrane 1999: 6; Leone and Fry 1999: 382). Versions of these mojo bags are still used today (Figure 4). There are also descriptions of these mojos being made in bottles which include pins, needles, red flannel, and urine or whiskey (Manning 2012: 134). The use of red flannel appears to be West African, although some English witch bottles contained a red felt heart. The color of the cloth was believed to increase the potency of the objects and the protective charm itself because of its association with blood, birth, death, sunrise, and sunset (Anderson 2002:130; Leone and Fry 1999: 382; Manning 2012: 134). Red was also believed to be the favorite color of spirits (Anderson 2002:130).

The Maynard-Burgess House “bottle charm” contains iron and copper pins, as well as red fabric often found in both European witch bottles and Hoodoo spiritual bundles. It is unclear what liquid was in the bottle since a sample was not tested or retained after it was excavated. It may have been urine, whiskey, or some other liquid. Another element of the Maynard-Burgess House bottle charm that may represent Hoodoo spiritual practice are the paper fragments pinned to the fabric. The paper may be the remains of what is known in Hoodoo practice as a “petition”, which is a request or wish written on a piece of paper that is then placed in a mojo bag or spell bottle (Patterson 2013: 21).

All evidence points to this bottle charm being placed in the ground by a member of the Burgess family for protection when the addition to the house was built in the 1940s. While we may never know the exact identity of that person, it shows that Hoodoo spiritual practice was alive and well in Annapolis in the mid-20th century.

References

Anderson, Jeffrey Elton

2002 Conjure in African-American Society. (Dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida).

Becker, Marshall Joseph

1980 “An American Witch Bottle.” Archaeology 33 (2): 18-23.

Cochran, Matthew

1999 “Hoodoo and Conjuration: Contextualizing nineteenth Century African-American Folk Practices.” Paper presented at the Council for Northeast Historical Archaeology Conference, St. Mary’s City, Maryland.

Leone, Mark P., and Gladys-Marie Fry

1999 “Conjuring in the Big House Kitchen: An Interpretation of African American Belief Systems Based on the Uses of Archaeology and Folklore Sources. Journal of American Folklore, 112 (445): 372-403.

Lockhart, Bill, Beau Schriever, Bill Lindsey, and Carol Serr

N.D. Fairmount Glass Works. Web Resource: https://sha.org/bottle/pdffiles/FairmountGlass.pdf accessed on February 23, 2021.

Manning, M. Chris

2012 Homemade Magic: Concealed Deposits in Architectural Contexts in the Eastern United States. (Master’s thesis, Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana).

Merrifield, Ralph

1987 The Archaeology of Ritual and Magic. London: B.T. Batsford Limited.

Mullins, Paul R. and Mark S. Warner

1993 Final Archaeological Investigations at the Maynard-Burgess House (18AP64). An 1850-1980 African-American Household in Annapolis Maryland, Volume I.

Patterson, Rachel

2013 Hoodoo: Folk Magic. Alresford, Hants, UK: John Hunt Publishing.

Rinquist, Abraham

2016 10 Secrets of Hoodoo Conjuring. Web Resource: https://listverse.com/2016/10/06/10-secrets-of-hoodoo-conjuring/ accessed on February 23, 2021.