Curator's Choice 2021

People and Pets as Property: An Exploration of a Collar

February 2021 By Sara Rivers Cofield, Curator of Federal Collections

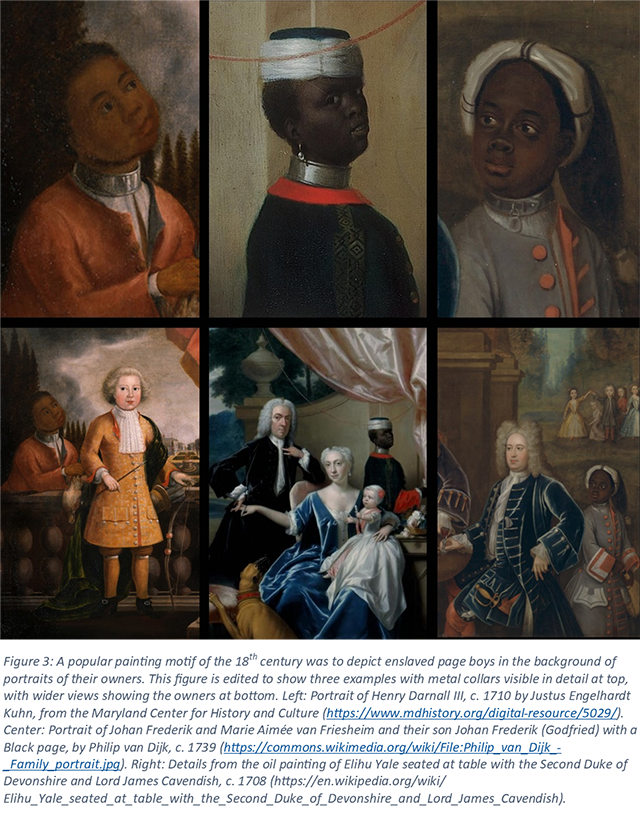

Some artifacts can really provoke an emotional response, and that was how I felt earlier this year when I stumbled across an ID for a metal band with holes in it that had been a mystery since its excavation in the 1980s (Figure 1). After seeing some comparable artifacts online, I thought it likely that this was part of a brass collar for a cherished dog or other pet, and I was excited to be able to share the feel-good cuteness of it (Figure 2). Everybody loves a good pet story, right? But then I remembered that period paintings sometimes depict slaves wearing such collars and had the sad realization that I had to investigate whether this collar had been used on a pet or a person (Figure 3).

Some artifacts can really provoke an emotional response, and that was how I felt earlier this year when I stumbled across an ID for a metal band with holes in it that had been a mystery since its excavation in the 1980s (Figure 1). After seeing some comparable artifacts online, I thought it likely that this was part of a brass collar for a cherished dog or other pet, and I was excited to be able to share the feel-good cuteness of it (Figure 2). Everybody loves a good pet story, right? But then I remembered that period paintings sometimes depict slaves wearing such collars and had the sad realization that I had to investigate whether this collar had been used on a pet or a person (Figure 3).

The collar fragment was recovered in the cellar of a house built around 1690 which burned down by 1730. The house was part of the Addison plantation, located near what is today National Harbor and the Route 210 interchange with the D.C. Beltway. In the 17th and 18th centuries the Addisons were a well-to-do merchant-planter family who relied on slave labor. In 1727, around the time the house burned, and the collar was sealed underground, over 75 slaves lived on the plantation. Was the collar purchased for use on one of these people?

Preliminary internet research suggests that collars used on slaves seem more likely to have been made of silver, not brass. Additionally, it is possible that collars used on people had the holes running perpendicular to

the collar, rather than in parallel such as the Addison example. The holes were made for a loop to pass through for the placement of a padlock. Those paintings I could find of people in collars where the holes were visible had perpendicular holes, perhaps because this arrangement allowed for more holes and finer adjustments. For many examples of paintings showing the use of such collars on slaves, see “18th-century portrait paintings with black slaves” on Wikimedia Commons.

So the likelihood is that the collar from Addison was for a dog or other pet, but having done this research the, “Aw shucks, they loved their dog” story I had originally envisioned feels irrelevant. The fact that I had to do research to determine if a stiff metal padlocked collar was used on a human being instead motivated me to think about how the people who purchased this artifact justified treating both pets and people as property.

It is common in the present to condemn slavery as unconscionable while withholding judgment of the people who perpetrated the institution in the 18th century because, “that’s just how things were back then.” But this collar and the plantation that yielded it offer a chance to really consider how individuals who were motivated by the economic need for cheap labor adopted and enforced the concept that humanity had superior and inferior “races” that they themselves defined. African slavery didn’t just appear in the colonies as a fully formed system. Colonial plantation owners and political leaders made conscious decisions and laws over time that resulted in a shift from the use of indentured servants, who were given freedom after a set number of years, to slavery for life based on skin color and racialized notions of blood relationships. The Addisons were active players in this system.

An inventory of John Addison’s estate taken at his death in 1709 included 11 “Negro” slaves, 2 “mallatow” slaves, and one indentured servant (for the full inventory transcription, see http://colonialencounters.org/Files/ProbateInventories/John-Addison.pdf). By the time his son died in 1727, the population was significantly more, with 54 “Negro” slaves living at outlying quarters and 11 “Negro” slaves, 11 “Molato” slaves, one “Indian” slave, and three indentured servants at the great house (See a scan of the original inventory at http://mdhistory.msa.maryland.gov/msaref10/msa_te_1_015/html/msa_te_1_015-0150.html). While inventories do little to shed light on the lives of individuals and families, these counts do illustrate the details that were most important to the planters. Aside from ages and cash value placed on people, the differentiation between slaves as “Negro,” “Molato,” “Indian,” and indentured, and the placement of all non-negro slaves and servants at the great house, is suggestive of the hierarchical values imposed by the plantation owners on people of different perceived races.

It is well documented that English society was somewhat obsessively class-based in the 18th century, and class was typically inherited. Within this system, “betters” were expected to rule while inferiors were expected to “know their place.” In justifying the shift to instituting slavery for life, those in power capitalized on the otherness of African peoples, considering them “savages” and putting them at the bottom of the social strata. Adherents to the concept of superior and inferior races then proceeded to lump people into groups and make sweeping generalities about their characteristics and capabilities according to the level of blood ties with the different races they defined.

While many accepted this as an accurate representation of humanity’s variation, and even considered it a scientifically founded reality not unlike the arrangement of species into a taxonomy, the idea that one’s level of humanity could be parsed out into “more” or “less” human was not universally accepted. For example, writers and moralists did debate such things as whether Africans had souls, and if so, if enslavement could be ethical.

Proponents of slavery defended its use and assuaged the discomfort they themselves might have felt about owning other humans with varied justifications. Some people argued that slavery could not be wrong because it was in the Bible. Others argued that “savage” cultures benefitted from integration into “civilized” society, but that they were not capable of caring for themselves properly. Through the lens of these arguments, many planters considered enslavement, with its guaranteed housing and food, as Biblical, charitable, and kind. Slaves therefore should be grateful, loyal, and obedient in return for having been saved from a savage land and assured of having a home.

Within the framework of institutional slavery, the planter classes exhibited their delusions of superiority and charity through material culture, such as fancy collars not unlike those used on pets. The collar was a symbol of ownership and control, but like an expensive necklace purchased by an abusive spouse, it was probably also perceived by the purchaser as a symbol of love. The assumption that this love should be mutual is evident in paintings of wealthy people with collared page boys, servants, dogs, and other pets looking at their owners adoringly.

I chose this collar as a Curator’s Choice because it makes me incredibly sad and uncomfortable that I had to figure out whether it was locked on to a dog or a person. That discomfort feels entirely appropriate after a year in which the persistence of race-based inequity in the U.S. has been at the forefront of the news. While we can all admire the concepts of liberty and equality that our nation was founded on, we cannot ignore the reality that the people who wrote many of those beloved concepts— Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, George Mason, and others— were planters who built wealth by owning human beings. These founding fathers were both brilliant and profoundly hypocritical in their actions, and it is problematic for people today to remember them as either heroic or evil, instead of a little bit of both. This collar helps me sit with and internalize the contradictory legacy of a nation that was simultaneously founded upon freedom, liberty, and the economic benefits of slavery. It is a wonder and a miracle to me that people who saw humans as property and dressed them up much like they did their pets, could ever have drafted the founding documents that we hold so dear to this day. Since so many of the nation’s founders did not live those ideals themselves, it is no wonder that there is still much to do to combat the systemic racism that is also their legacy.